The basement of the Greenwood County Historical Society did not look like the kind of place where history-changing discoveries happen. The air smelled of dust and aging paper; fluorescent lights buzzed softly over rows of metal shelves stacked with boxes no one had opened in decades.

James Mitchell, a 38-year-old genealogist from Chicago, was down to his last box of the day. He had almost called it a night when he saw the label:

“Miscellaneous Personal Effects, 1918–1925.”

He opened it expecting nothing unusual—old receipts, brittle letters, maybe a ribbon or two. Instead, wrapped in tissue and remarkably well preserved, was a studio portrait mounted on thick cardboard.

Stamped along the bottom:

Crawford Photography, Greenwood, Mississippi — March 1920.

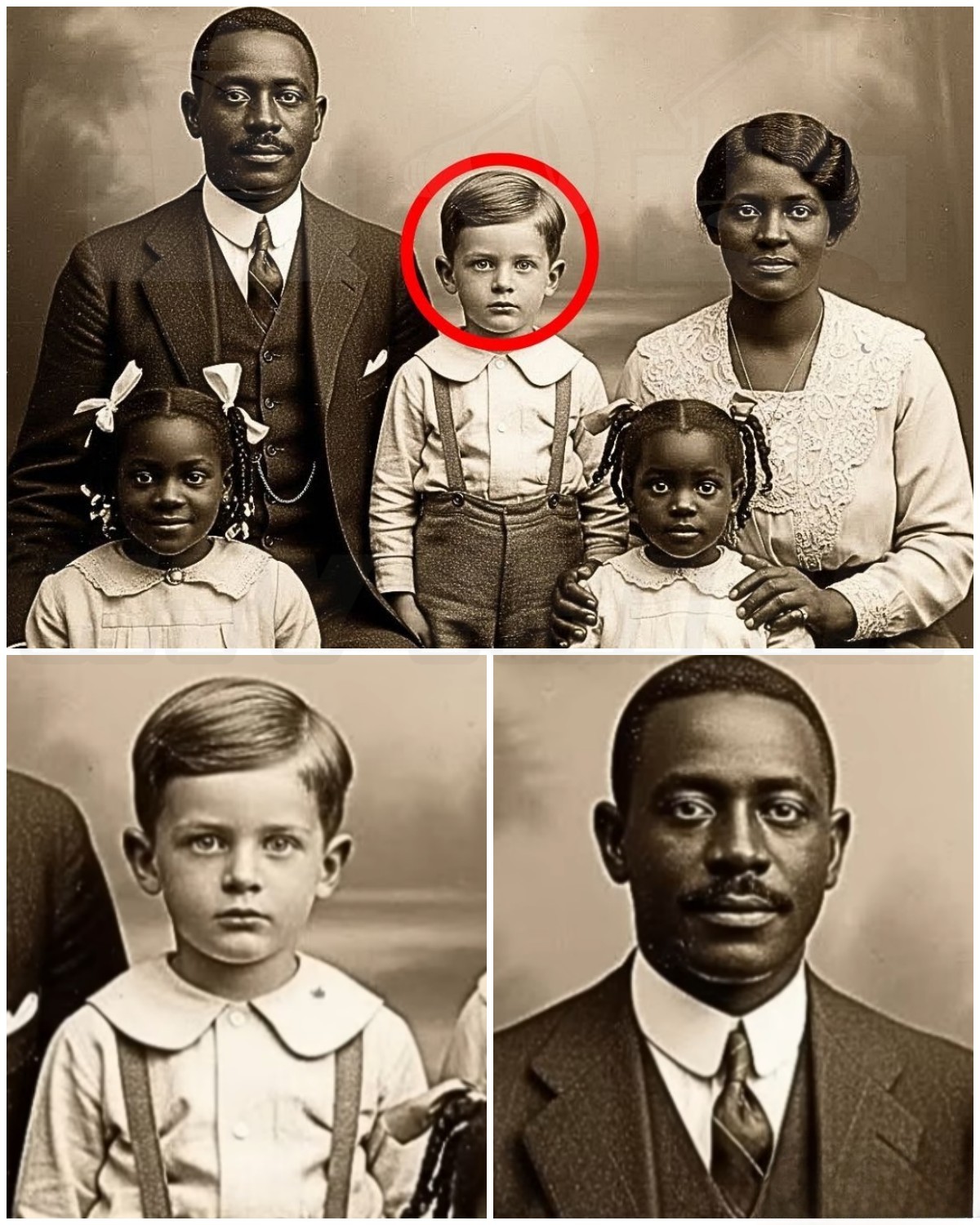

In the image, a dignified Black couple sat at the center. The man wore a pressed dark suit, his expression calm and steady. The woman sat beside him in an immaculate dress, hands folded with quiet composure. Two girls, around eight and ten, stood on either side in pristine white dresses with carefully tied ribbons in their braids.

Standing between them, slightly in front, was a boy.

A white boy.

His skin was pale, his hair light brown and wavy, his eyes—though captured in sepia—clearly light.

He stood close to the man, the man’s hand resting gently on his shoulder, as if the child fully belonged there.

On the back, in faded pencil, someone had written:

“Samuel, Clara, Ruth, Dorothy, and Thomas. March 14, 1920.”

Four names fit the picture. One did not.

In Mississippi in 1920—under Jim Crow laws, segregation, and constant racial tension—a proud studio portrait of a Black family openly posed with a white child was more than unusual. It was risky. Potentially life-threatening.

James realized he was holding something that did not make sense for its time.

The Photo No One Could Explain

He carried the portrait upstairs to the reference desk, where Mrs. Patterson, the elderly archivist, was preparing to close.

When she saw the photograph, something flickered across her face—recognition mixed with hesitation.

“That’s Samuel and Clara Johnson,” she said quietly. “He was a respected carpenter. She did sewing and mending for half the town. Their daughters were Ruth and Dorothy.”

“And the boy?” James asked.

Mrs. Patterson paused as though weighing whether to share what she knew.

“I’ve heard stories,” she said. “Stories people stopped telling a long time ago. If you want more than rumor, you should talk to Evelyn Price. She’s ninety-three now. Her mother knew the Johnsons. If anyone can help you, it’s her.”

She looked at the photo one more time, then back at James.

“No one has ever really followed up on that picture,” she added. “Maybe it’s time someone did.”

A Child Without a Record

Back at his hotel that night, James opened his laptop and began the work he knew best: methodical research.

The 1920 census confirmed Samuel and Clara Johnson living in Greenwood with two daughters, Ruth and Dorothy. There was no son, no “Thomas,” no other child listed in their household.

He checked county birth records for a Black boy named Thomas Johnson born around 1913–1914.

Nothing.

The boy in the photograph didn’t match the records because he wasn’t their biological child.

Then James found a newspaper clipping from February 1920 in the archives of the local paper, the Greenwood Commonwealth:

A house fire had claimed the lives of Robert and Margaret Hayes. They left behind one child: a six-year-old son.

The article named the parents, described the fire, and mentioned the surviving boy. But after that, the trail went cold—no mention of where the child was placed, no follow-up about relatives or guardians.

James searched records for the Greenwood County Children’s Home, the institution that normally handled orphans. Historical notes showed investigations into neglect, forced labor, and disappearances. It had a reputation as a place children entered but did not always leave.

If Samuel and Clara had stepped in before officials arrived, they might have kept the boy out of that system.

James sketched a rough timeline:

- February 1, 1920 – Robert and Margaret Hayes die in a house fire.

- February 3, 1920 – Article reports a six-year-old orphaned son.

- March 14, 1920 – Studio portrait of the Johnsons with a white boy named Thomas.

Six weeks. Enough time for a quiet act of rescue—and the beginning of a story that had never been properly told.

Hearing the Story From Someone Who Lived It

The next day, James drove to Magnolia Gardens, a retirement community shaded by old oak trees. There, in a bright sunroom, he met Evelyn Price, still sharp in mind despite her age.

He handed her the portrait.

Evelyn held it with surprising steadiness. Her eyes softened.

“Yes,” she said, “that’s Samuel and Clara. I was a little girl when they were alive, but my mother talked about them often.”

“And the boy?” James asked.

Evelyn nodded slowly.

“You have to understand 1920 Mississippi,” she said. “A Black man could be violently punished for even the appearance of impropriety with a white child. But they took him in anyway.”

She explained what her mother had told her.

After the fire, Samuel had seen the Hayes boy sitting alone on the charred steps of his ruined home. County officials were on their way to place him in the children’s home—a place everyone in the Black community knew to fear.

Samuel went home and told Clara. They both understood the risks. Still, Clara reportedly said, “I can’t send any child to that place, no matter his color.”

With quiet cooperation from neighbors, they agreed to hide the boy in plain sight. They told outsiders he was a mixed-race nephew from out of town. Within the Black community, people knew the truth but protected the secret.

For nearly two years, the boy lived as part of the Johnson family.

“They called him Thomas,” Evelyn said. “He followed Samuel around the workshop. Played with Ruth and Dorothy. Called them ‘Mama’ and ‘Papa.’”

But by 1922, the danger was growing. Local racist groups were becoming more active. Thomas, now older, looked increasingly white, which made the family more vulnerable.

So Clara and Samuel made a difficult decision: they arranged for him to travel north to Chicago, to live with Clara’s cousin, a woman named Diane Porter who was married to a white union organizer. In a northern city, his presence in a mixed household would attract less lethal scrutiny.

“Letters came for a while,” Evelyn said. “Then they stopped. But my mother always said Samuel and Clara never regretted what they did. They knew what it had cost them to keep him safe.”

She handed the photo back to James.

“Tell it right,” she said. “People should know this happened.”

The Church That Helped Keep the Secret

James’s next stop was Mount Zion Baptist Church, where the Johnson family had once been active members. Pastor Marcus Williams and church secretary Patricia Lewis listened carefully as he described his findings.

When he showed them the portrait, they exchanged a look that told James there was more to learn.

In the church basement, they unlocked a cabinet holding old ledgers and handwritten minutes. In a membership record from the early 1920s, James found an entry:

“Samuel and Clara Johnson with daughters Ruth and Dorothy and ward Thomas, age six. May the Lord protect this household in their righteous work.”

The entire congregation had known—and quietly agreed to protect the boy.

In the pastor’s journal from that era, James read a passage describing Samuel’s anguish over his decision to take in the child. The pastor had asked him why he was willing to risk so much.

Samuel’s answer had been recorded in simple words:

“I saw my own daughters in that boy’s eyes.”

Another entry years later noted that the boy had been sent north for his safety and that Clara had cried for days.

Finally, Pastor Williams produced an item that had been saved for generations: a letter from Chicago, dated 1922, written in a child’s handwriting.

“Dear Reverend,

I arrived safely. Please tell Mama Clara and Papa Samuel that I love them and I am being good.

—Thomas”

The letter confirmed the story: the boy had survived, reached Chicago, and remembered the people who took him in as his parents.

Tracing Thomas Through Time

Back in Chicago, James followed Thomas’s trail through modern records.

On the 1930 census, he found a “nephew” listed in the household of Diane Porter. Later records showed him as Thomas Hayes—a carpenter by trade, just like Samuel Johnson.

He tracked down a marriage certificate, employment records, and eventually, a death certificate from 1987. Thomas had lived, worked, raised a family, and died in Chicago without ever officially documenting the full story of his childhood in Mississippi.

But he had kept one thing.

A carved wooden toy horse, carefully preserved in a box of keepsakes. The piece, signed with a small “S.J.” on the underside, had been made by Samuel.

One of Thomas’s grandchildren, a high school history teacher named Thomas Hayes Jr., had inherited it.

When James reached out and shared pieces of the story, Thomas Jr. agreed to meet. Seeing the 1920 portrait for the first time, he recognized his grandfather’s face in the small boy standing between the Johnson girls.

“My grandfather never talked about his early life,” he admitted. “Now I think I understand why.”

Two Families, One Shared Legacy

With the help of Pastor Williams and Patricia Lewis, James located descendants of Ruth and Dorothy, the Johnson daughters.

Ruth’s line had settled in Memphis. Dorothy’s descendants still had strong ties to Greenwood—Patricia and Pastor Williams themselves were part of that branch.

A private gathering was arranged at Mount Zion Baptist Church.

The Johnson descendants and the Hayes descendants met for the first time beneath the same roof where the congregation had once prayed for Samuel and Clara’s safety.

The 1920 portrait was displayed at the front of the sanctuary.

Thomas Hayes Jr. spoke about his grandfather’s life in Chicago, his work as a carpenter, and the quiet way he had carried himself. Pastor Williams shared stories handed down about Samuel and Clara’s courage and the support they’d received from their community.

Then, in a simple gesture, Thomas Jr. handed the carved wooden horse to Ruth’s granddaughter.

“This was made by your ancestor,” he said. “My grandfather kept it his entire life. I think it belongs with your family now. He never forgot where it came from—or who gave him a chance to live.”

There were no reporters present, no cameras in their faces—just two families finally learning how closely their histories were intertwined.

The Portrait’s New Meaning

In the months that followed, the story of the 1920 photograph spread beyond Greenwood and Chicago. It became more than just an archival curiosity; it became a symbol of quiet moral courage in a dangerous time.

Historians began using the case to talk about interracial solidarity under Jim Crow, about the way communities sometimes defied unjust systems at great personal risk. Educators shared it with students as an example of how ordinary people can make extraordinary choices.

The Johnson home in Greenwood was eventually marked with a historical plaque. Plans emerged to preserve it as a small museum dedicated not only to the family, but to the many unrecorded acts of protection and care that never made it into official history.

The original portrait, once buried in a box in a basement archive, is now preserved in climate-controlled conditions and periodically exhibited.

For James, the genealogist who opened a box he almost left for another day, the lesson is simple:

“Sometimes the records don’t tell the whole story,” he says. “Sometimes a photograph, a letter, or a carved toy is the only surviving proof of incredible bravery. All it takes is one person willing to ask, ‘Who are these people, and what did they do?’”

A century after the shutter clicked in a Mississippi studio, the mystery of the 1920 portrait has finally been resolved—not as a tale of scandal or intrigue, but as a story of compassion that refused to fit the rules of its time.