The attic of the Whitcombe House in rural Massachusetts was the last place anyone expected to find a piece of photographic history. The home, slated for an estate sale after decades of vacancy, still held trunks, furniture, and old albums untouched by time. Most of the items were typical for a late-19th-century household—hand-stitched quilts, faded newspapers, family documents, and dozens of early photographs in varying stages of preservation.

One album, bound in worn leather and tied with an aged ribbon, quickly drew the attention of antique buyers and historians assisting with the cataloging process. Many of the images inside were ordinary: families standing formally in front of their homes, children posed stiffly in studio settings, and outdoor photographs capturing the landscape of a farming town in the 1800s.

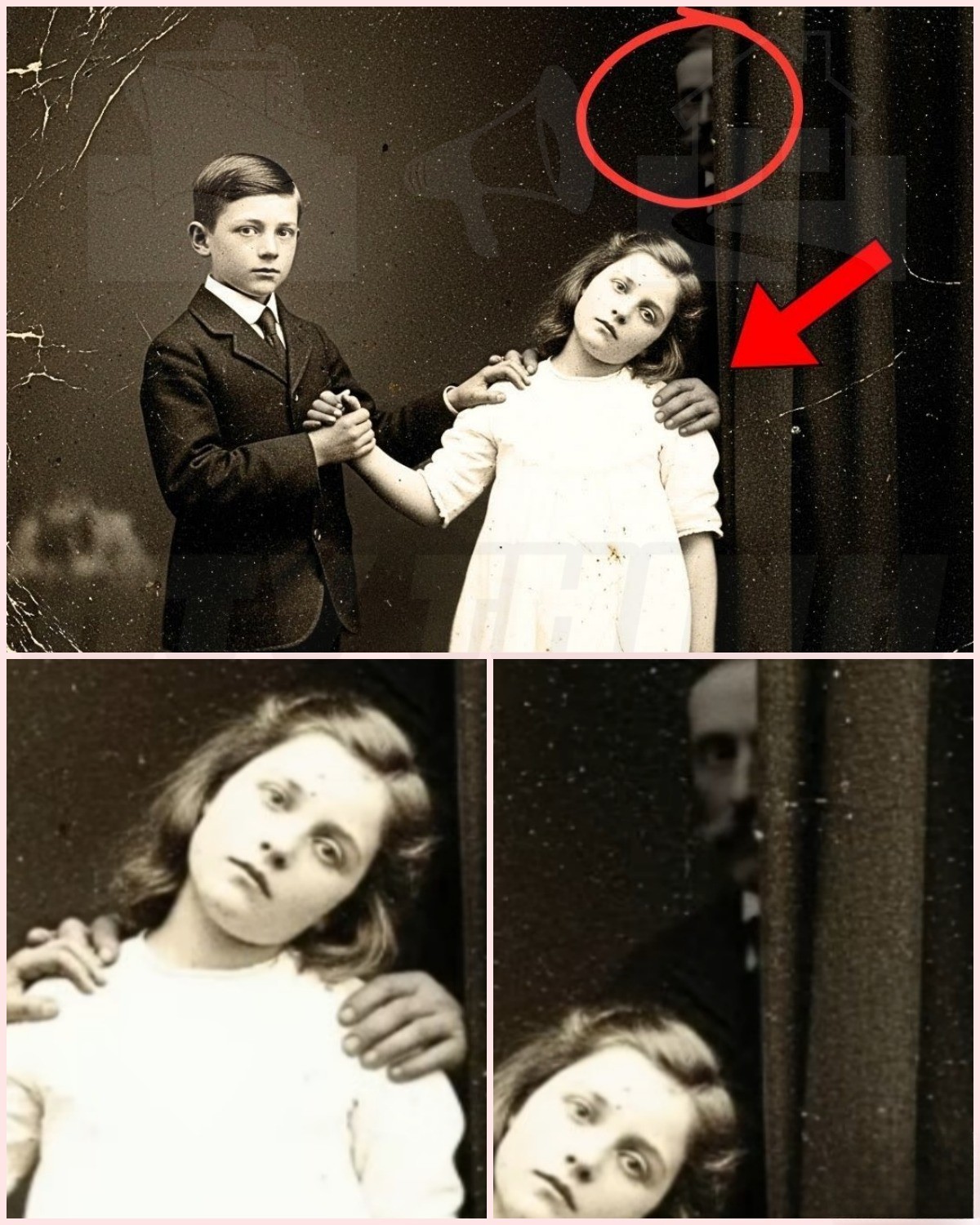

But one photograph stood out, not for anything dramatic, but for a puzzling composition. It showed a young boy, perhaps eight or nine, holding the hand of a small girl dressed in white. The children appeared to be siblings. Their clothing was typical for 1899, and their expressions—calm, subdued—reflected the photographic norms of the Victorian era, when long exposure times required sitters to remain completely still.

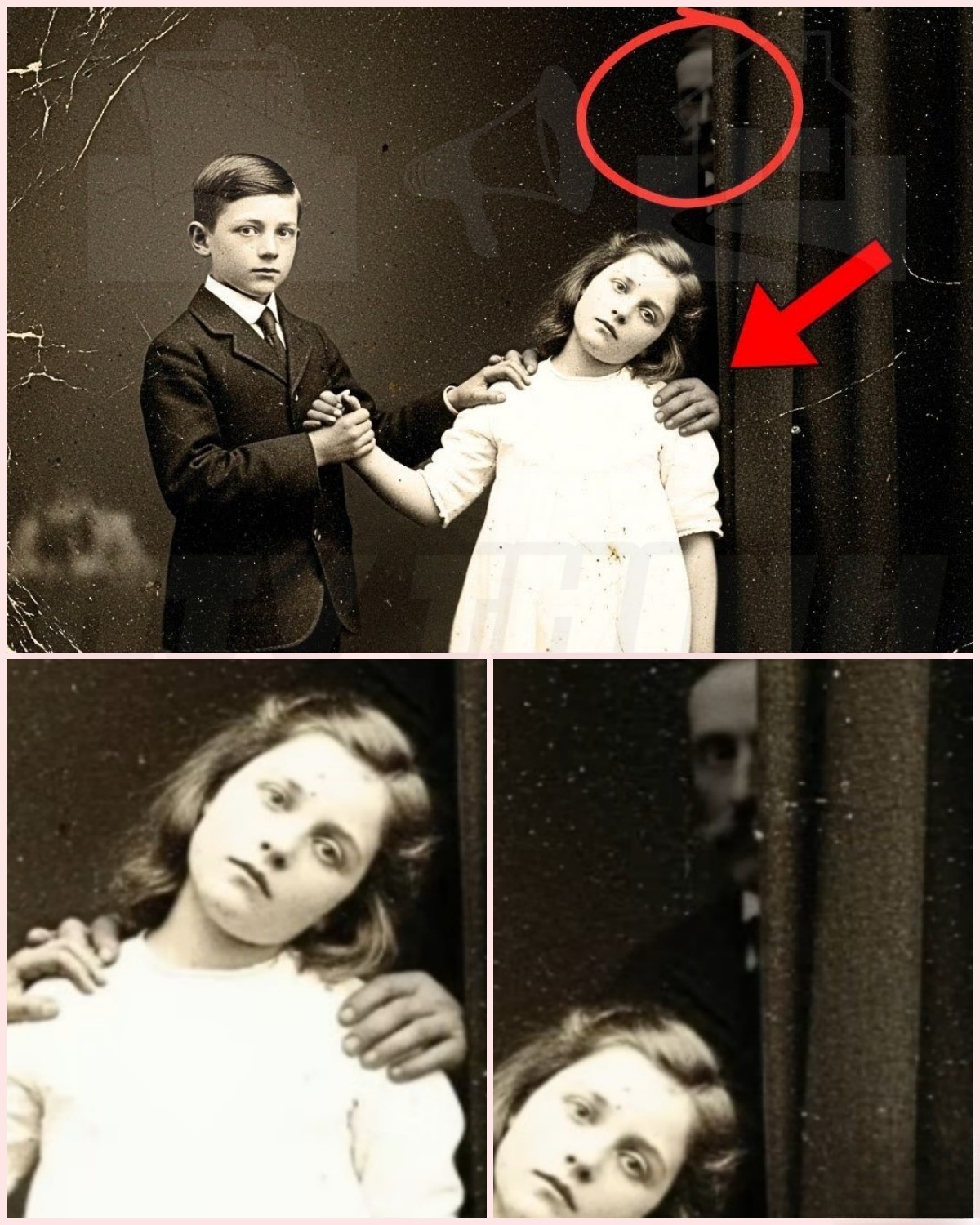

The girl’s posture, however, seemed unusual. Her head angled downward, and her arms rested loosely at her sides. A large portion of the photograph was obscured by scratches and discoloration, making it difficult to interpret the scene fully. Whoever had taken the photo had also placed a curtain or backdrop behind the children, much like those used in small-town photographic studios.

The ambiguity surrounding the image drew curiosity. One buyer, a collector named Marjorie Hemsley, purchased the album and decided to send the photograph for professional restoration—not out of fear or intrigue, but simply because historical photographs often reveal unexpected details once cleaned and digitally enhanced.

What she received in return, however, was not scandal, mystery, or danger—but a clearer understanding of 19th-century photography practices and a forgotten moment in a family’s life.

Restoration Reveals a Common 19th-Century Practice

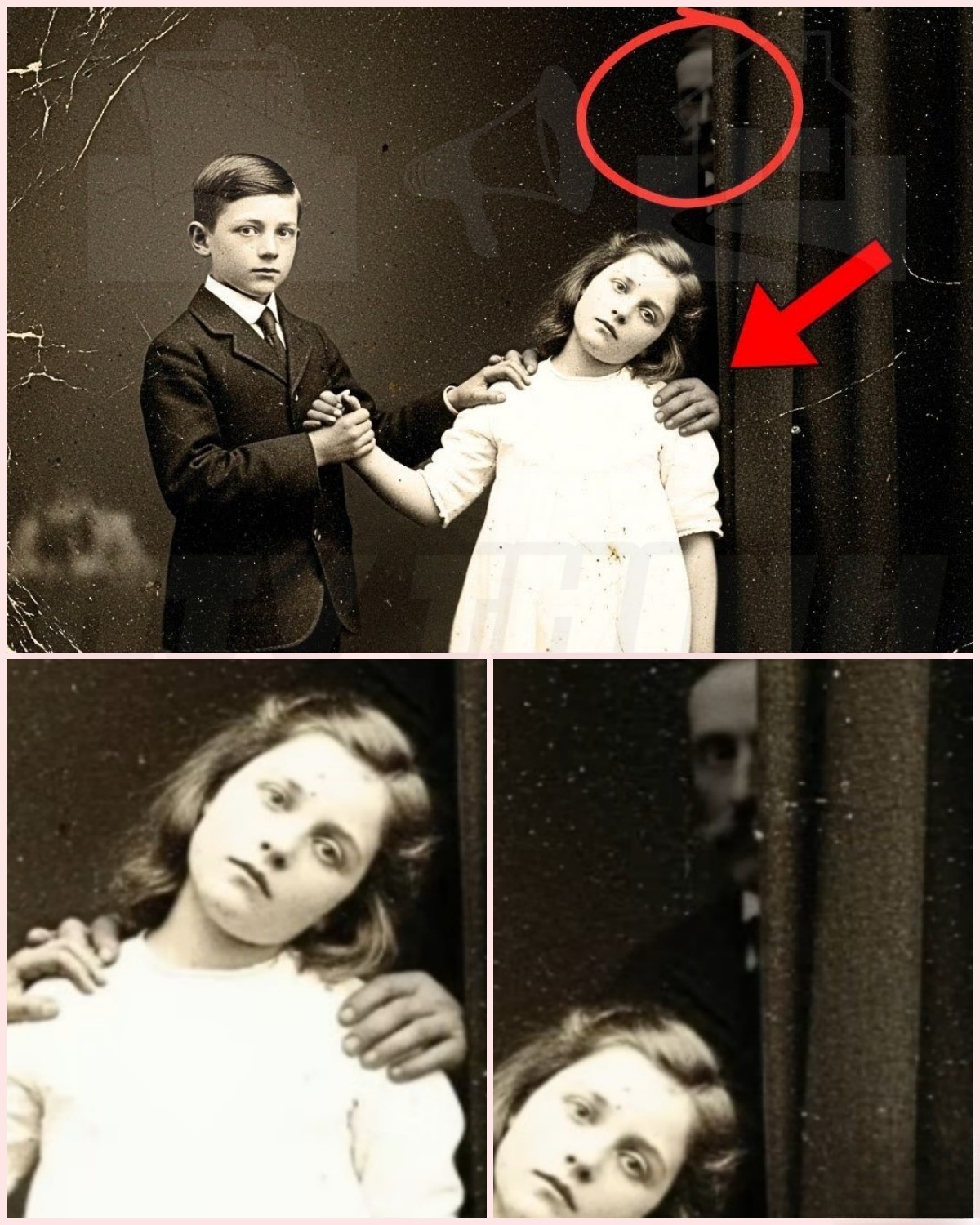

When the restored version was displayed on a monitor a week later, Marjorie was struck by how different the image looked. The lighting, textures, and small details—like the stitching on the children’s clothing and the shape of their shoes—were now visible. Most surprising was the discovery of a partially obscured adult figure standing behind the curtain, previously hidden by damage and deterioration.

This was not unusual to historians. In the 19th century, especially in rural areas, adult assistants or photographers often steadied young children during long exposure times. The presence of a partially visible adult’s hand or clothing in historical photos is a documented phenomenon. Children often struggled to remain still for the several seconds required for exposure, so adults frequently supported them just outside the frame.

What had originally appeared ambiguous or unsettling was now recognized as a commonplace technique of early photography: an adult standing close enough to support the children but positioned behind a curtain so the focus would remain on the young subjects.

The man’s role was technical, not symbolic, and the restoration corrected decades of misinterpretation caused by discoloration and damage.

A Glimpse Into Victorian Family Life

With the restored image in hand, Marjorie returned to the album to piece together the children’s story. Several earlier photographs showed the siblings in more casual settings—playing with a dog, holding toys, or posing with other family members. These images reflected the gradual shift in late-19th-century photography toward more personal, candid-style documentation.

One particular photograph dated a few months prior showed the girl smiling while holding a doll, offering a rare instance of levity in an era known for solemn expressions. Another image captured the boy standing proudly alongside his father in front of a small barn.

The photograph that had captured so much initial attention turned out to be a formal portrait taken during a difficult time for the family. A page preceding the portrait revealed a funeral photograph showing adults in dark clothing surrounding a small white coffin. Victorian mourning customs were highly structured, and families often documented such events as part of their historical record. These photographs were not intended to evoke fear or sadness, but to honor and remember those who had passed away.

The image of the boy holding his sister’s hand, therefore, was part of a broader and culturally understood practice known today as memorial portraiture. The intent behind it was reverence, not secrecy—an attempt by the family to preserve their child’s memory in the only permanent form available to them at the time.

Historical Records Clarify the Event Further

Intrigued by the cultural context, Marjorie searched through county archives to see whether records about the Whitcombe family still existed. The family had lived in the region between 1872 and 1911, and although few documents survived, she located several newspaper clippings that provided clarity.

A local newspaper from late 1899 described a brief illness that had affected several children in the community, including one member of the Whitcombe family. Rural communities during that period experienced recurring outbreaks of childhood disease, long before widespread vaccination and modern treatments. Although no detailed medical records survived, the article mentioned that a local doctor, Alistair Greaves, had attended to multiple households and assisted families during a period of grief.

This aligned with the presence of the adult figure in the restored photograph. Early rural photographers were often also community professionals—teachers, clergy members, or in some cases, physicians who owned basic photographic equipment. In small towns without full photography studios, family portraits were sometimes taken by community members familiar with the equipment.

The adult figure seen behind the curtain was therefore likely the photographer or an assistant helping to maintain stability during the long exposure.

The Boy’s Diary Provides Insight Into the Family, Not Mystery

In a second trunk from the estate office, Marjorie uncovered a small journal belonging to the young boy. The entries were simple, childlike, and brief, focusing mostly on daily routines, chores, schoolwork, and family life. Only one entry mentioned the day of the photograph:

“Mr. Greaves says I must hold still so the picture will work. Mama says this will help us remember her.”

This sentence, ordinary in tone, clarified the context definitively. The portrait was a memorial image taken respectfully during a difficult period for the family. It reflected a cultural practice common in the 19th century, not a mystery or hidden wrongdoing.

Preservation Over Sensationalism

As the restored photograph circulated among archivists and historians, the professional consensus was unanimous: the image was an authentic piece of Victorian mourning culture. The partial presence of the adult figure behind the curtain was not evidence of anything unusual, but rather a practical necessity of early photography.

The emotional weight of the image came not from fear or confusion, but from its historical authenticity—an intimate record of a family coping with loss. It served as a reminder that photographs of the period captured both the ordinary and the difficult moments of life, preserving them for future generations to study and understand.

Today, the restored photograph is preserved in an archival collection documenting late-19th-century American family practices. Far from being a source of alarm, it is now regarded as a valuable teaching tool about early photographic methods, cultural rituals, and the ways families honored their loved ones during a period in which photographic opportunities were limited.

Through careful restoration and research, what once appeared puzzling or unsettling became an example of how context transforms interpretation—and how history becomes clearer when examined with care, respect, and expertise.

Sources

- The Thanatos Archive – Victorian Memorial Photography Collection

- Library of Congress – 19th-Century American Photography Practices

- Massachusetts Historical Society – Records of Rural Families, 1870–1910

- Journal of Photographic History – Techniques of Early Exposure Stabilization