I. A Name History Tried to Erase

Hidden in scattered records from antebellum Louisiana—plantation books, private diaries, auction receipts—appears a name that should have been central to any honest history of slavery and its brutal economy.

A man whose life should be taught in classrooms, quoted in documentaries, and examined in serious scholarship.

Instead, he was deliberately pushed into the margins.

He shows up in:

- coded references

- brief mentions in estate papers

- fragments of stories passed down through families long after emancipation

- and, most disturbingly, in the personal writings of wealthy men who had powerful reasons to cover up his existence

To white planters in St. Landry Parish, he was legally “property.”

To enslaved people, he became legend.

To the historical record, he is almost nonexistent.

But in the unofficial memory of the Deep South, he carried another identity:

The “Bayou Giant.”

The undefeated fighter.

The enslaved man who faced 37 opponents in secret plantation rings—and was never once beaten.

This is the story of a man who should not have survived, a system that should never have existed, and a legacy the South did everything it could to bury.

II. St. Landry Parish: A Landscape Built for Profit and Control

In 1847, St. Landry Parish was among the wealthiest sugar-producing areas in the United States. The land was flat, intensely humid, and highly productive—cut by swamps, marshes, and waterways feeding into the Atchafalaya Basin.

At the top of this economic pyramid were the plantation owners:

- extremely wealthy

- politically influential

- socially protected

- absolutely committed to maintaining control over the people whose labor made their fortunes possible

One of the most powerful was Charles Bogard Marshand, a 38-year-old planter whose 3,000-acre property near Opelousas embodied both the cruelty and ambition of Louisiana’s slave system.

He was known for sharp business instincts, cold efficiency—and for one private obsession that would alter several lives.

While others collected racing horses or imported rare wines, Marshand focused his energy on something else.

He wanted to own a fighter.

III. The Purchase That Changed a Life

In September 1847, a shipment of enslaved people arrived in New Orleans from the Carolinas. Among those sold was a man listed simply as:

“Samuel — approx. 24 years, 6’4”, 230 lbs, outstanding physical build.”

The bill of sale carried an unusual note:

“Strong-willed. Requires strict supervision.”

Samuel had been sold three times in four years. Each previous owner saw his physical potential but eventually decided he was “too much trouble.” His resistance tended to be subtle—hesitation, quiet defiance, a refusal to be completely submissive.

Most planters saw this as a liability.

Marshand saw it as potential.

He paid $800 for Samuel—almost double the usual price.

Other buyers laughed at his decision.

Three months later, none of them were laughing.

IV. A Plantation Owner Obsessed With Combat

The Marshand estate sat seven miles west of Opelousas, at the end of roads that turned to deep mud whenever heavy rain came. The imposing main house was only the facade; behind it stretched the true heart of the operation:

- sugarcane fields

- a processing mill

- overseers’ quarters

- and rows of cramped cabins where enslaved people lived

Samuel was assigned to the stables—an odd choice for someone so physically imposing. Stable workers were usually chosen for reliability more than for strength.

But Marshand already had a plan.

For weeks, he quietly observed Samuel:

- the way he moved and carried himself

- how he reacted to orders and threats

- how quickly he sized up new situations

- and how other enslaved people slowly began to look to him

Marshand wasn’t searching for a compliant laborer.

He was evaluating a potential weapon.

Then, one afternoon in October, he saw what he’d been waiting for.

V. The Moment That Shaped a Monster’s Plan

Dutch Keller, a notoriously harsh overseer, accused Samuel of a small infraction and raised his whip to punish him.

Samuel stepped forward and caught Keller’s wrist mid-air.

No enslaved person was expected—or allowed—to do such a thing.

The stable went silent. Everyone understood what usually came next:

- public punishment

- severe beating

- a “lesson” for the entire plantation

But that day, something different happened.

Marshand appeared, took in the scene, and ordered Keller to leave.

The overseer argued—shouting about discipline and rules—but Marshand repeated the order in a tone that ended the discussion. Keller left, stunned and humiliated.

Alone in the stable, owner and enslaved man faced each other.

Then Marshand said:

“I know what you are. You won’t be broken.

I won’t waste time trying.

But I’m going to give you an arrangement.”

What he called an arrangement would become a sentence lasting nearly four years.

VI. An “Offer” That Was Really a Threat

Marshand’s proposal was clear and brutal.

Samuel would fight.

He would be entered into secret matches arranged between plantation owners.

These fights would sometimes end in serious injury—and sometimes in death.

If Samuel refused?

The people he had grown close to on the plantation—

- Dina, who worked in the kitchen

- Silas, the older man who guided him through the unspoken rules of the estate

- Marcus, the young boy who admired him

—would suffer the consequences.

They could be punished, sold away, or permanently separated from everyone they loved.

If Samuel agreed and won?

- they would be better protected

- they could receive improved food and treatment

- Samuel himself would get certain privileges

It was framed as a choice.

In reality, it was coercion.

The first match was scheduled for 14 November 1847.

VII. The Fighting Ring: Violence Turned Into Spectacle

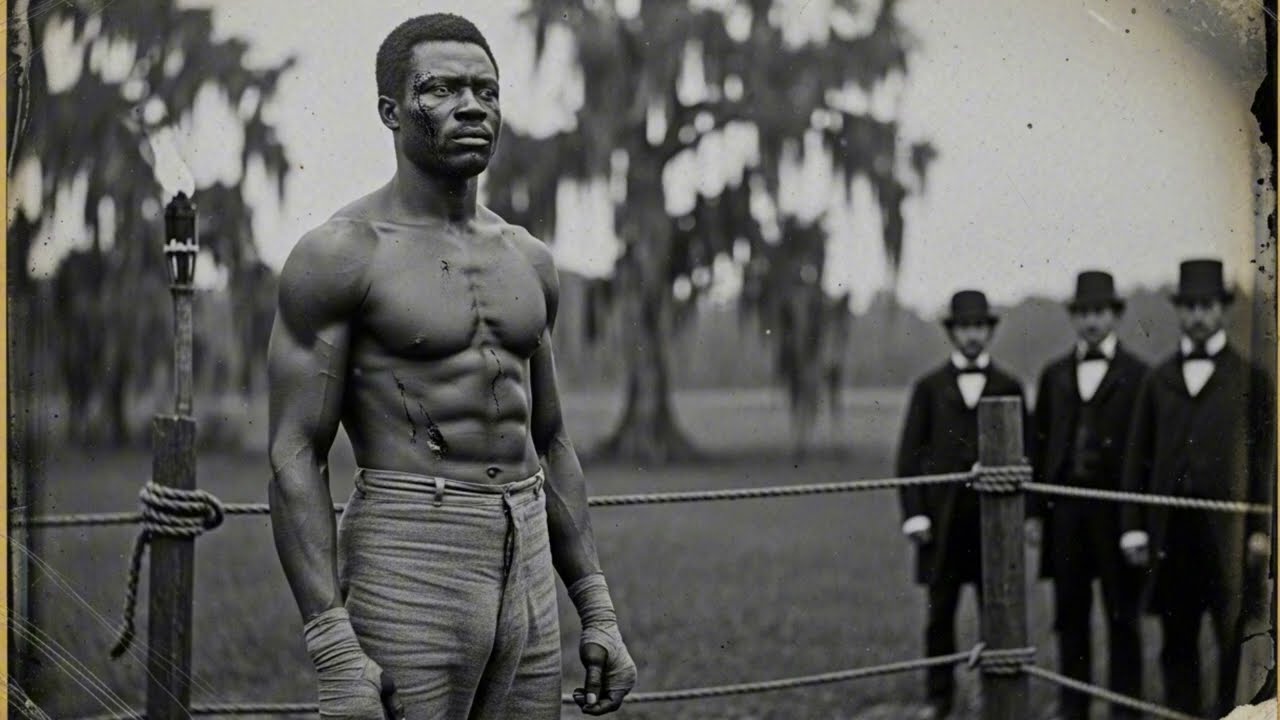

The “ring” was a rough clearing three miles from the main house. Torches outlined a circle. Wealthy men gathered there to gamble, drink, and watch enslaved men be forced into combat.

Samuel’s first opponent was Jupiter, a fighter with a fearsome reputation.

The match lasted around 17 minutes.

Jupiter was badly injured and died several days later.

Samuel stood in the dirt, bleeding and exhausted, waiting to be told what came next.

Marshand asked him quietly:

“Can you do that again?”

Samuel knew what was at stake for Dina, Silas, and Marcus.

“As long as I must,” he answered.

Over the next eighteen months, he stepped into the ring 11 more times.

- Eight of the men he fought did not survive their injuries.

- Three were left unable to work again.

Samuel never celebrated.

He never asked for recognition.

He did what he was forced to do, believing that every victory was a shield for the people he cared about.

Life on the plantation shifted.

- Other enslaved people viewed him with a mix of awe and unease.

- Overseers kept their distance.

- Even Keller avoided him.

Meanwhile, Marshand’s wealth grew with every match.

VIII. A Legend Grows Beyond the Plantation

By spring 1849, Samuel had fought nineteen times. Fourteen of his opponents had died as a result of their injuries. Word spread quickly across Louisiana:

From Baton Rouge to Lafayette to New Iberia, planters started traveling to see the “Bayou Giant” in person.

But Samuel was doing more than fighting.

He was listening.

Surrounded by planters who assumed he was “just muscle,” Samuel quietly collected information:

- business rivalries

- debts and alliances

- shipping schedules

- political tensions

- the strengths and weaknesses of the men who claimed to own him

With each bout, his body became more skilled. With each gathering, his understanding of the plantation world grew deeper.

His 20th opponent, Kato from Georgia, had already ended six other fighters’ careers.

The match lasted about 23 minutes.

Kato managed to injure Samuel’s ribs and knocked him down. Spectators thought the undefeated streak was about to end.

Samuel stood back up.

What followed rattled even those who profited from the fights. Samuel systematically took control of the match and ultimately left Kato fatally injured.

Later, Marshand asked why Samuel had seemed to hold back earlier in the fight.

Samuel replied:

“I was teaching him something.

And everyone watching.”

IX. When the Matches Became a Problem

Between April 1849 and September 1850, Samuel fought 12 more times.

- Ten opponents died from their injuries.

- Two were left permanently disabled.

Among enslaved people, Samuel became a symbol—not of invincibility in a magical sense, but of a human being who refused to be broken.

Among planters and overseers, unease grew.

- Some feared what might happen if an enslaved man with this kind of reputation decided to turn his strength against them.

- Others resented the money Marshand was making from the matches.

Rumors took shape:

Samuel was the man who simply could not be beaten.

And that reputation began to slip out of Marshand’s control.

X. The 32nd Fight: A Few Words That Sparked a Movement

In October 1850, Samuel faced Caesar, another highly trained fighter with a reputation for extreme toughness.

The match lasted about half an hour. Caesar later died as a result of his injuries.

After the fight, an enslaved man stepped out from the crowd and quietly asked Samuel:

“How many?”

Samuel answered:

“Thirty-two.”

The man then asked:

“And they still haven’t taken you down?”

The exchange itself was brief, but its meaning spread quickly among enslaved communities in the region.

Samuel wasn’t merely surviving the system.

He was, in a limited and tragic way, outlasting the very violence meant to crush him.

XI. Fight 36 and a Warning

At some point, the violence nearly spilled into everyday plantation life. An incident between Samuel and a younger overseer ended with the overseer severely injured.

That shook Marshand.

He began to think about ending the matches altogether after one final series. He planned to withdraw Samuel after a 36th fight—this time against a man nicknamed Goliath, raised and trained specifically for these brutal spectacles.

The match lasted about 42 minutes.

Goliath did not survive.

Samuel, standing there battered but still undefeated, turned to Marshand and said:

“One more.

Thirty-seven.”

When Marshand asked why that number mattered, Samuel replied only:

“Because that’s how many it takes.”

It was the clearest hint he ever gave about his personal calculation.

XII. A Plot to Silence Him Forever

For fight 37, Samuel’s opponent would be Ajax, a Caribbean fighter with nine recorded kills to his name.

But there was another plan in motion.

A group of planters—angry about their gambling losses, nervous about Samuel’s reputation, and jealous of Marshand’s profits—agreed that, if Ajax lost, Samuel had to be eliminated.

They brought rifles.

They arranged themselves around the clearing.

They intended to shoot Samuel as soon as the match ended.

Through a chain of enslaved messengers, news of this plot reached Marshand.

He warned Samuel and urged him to flee before the match.

Samuel refused.

“Thirty-seven fights,” he said.

“That’s what it takes.”

What he meant would only become clear later.

XIII. The Last Fight in the Swamp

On 17 March 1851, a crowd gathered at a hidden clearing in the Atchafalaya Basin, reachable only by narrow, swampy paths.

Ajax was powerful, disciplined, and confident.

Samuel was injured, exhausted from years of fighting, and fully aware that men with guns waited in the shadows.

The bout lasted around 33 minutes. It was one of the harshest contests spectators had ever witnessed, but accounts avoid graphic detail; what mattered most was the outcome.

Ajax collapsed after a final decisive blow to the head and did not recover.

Samuel, though barely able to stand, remained on his feet.

That was the signal.

Talbot, one of the conspirators, raised his hand. Rifles were lifted. The plan was to end Samuel’s life then and there.

What happened next altered everything.

XIV. A Line No One Expected

Before the shooters could pull their triggers, more than forty enslaved men from different plantations stepped between Samuel and the guns.

They did not yell.

They did not attack.

They did not brandish weapons.

They simply stood together, forming a human barrier.

To kill Samuel now, the planters would have to fire into this crowd—destroying people they themselves considered “valuable property” and risking a larger revolt.

Shooting into that group would:

- turn a secret spectacle into a regional crisis

- invite legal attention from authorities

- jeopardize their own fortunes

The men with rifles hesitated.

Then Marshand stepped forward and declared:

“The match is over.

Samuel won under the rules we all agreed to.

Anyone who objects is free to challenge me in court.”

No one pulled the trigger.

The assassination plot collapsed.

Samuel walked away from his thirty-seventh fight still undefeated.

XV. What 37 Victories Made Possible

In the weeks that followed, things began to change quietly:

- Dina was legally freed and moved to New Orleans.

- Silas gained manumission and resettled in Mobile.

- Marcus was placed in an apprenticeship and later became a trained carpenter.

Marshand offered to free Samuel as well.

Samuel said no.

“What about everyone still here?”

“I’ll stay. There’s work left to do.”

From that point, Samuel shifted his focus. He continued working on the plantation, outwardly following orders, but behind the scenes he:

- helped arrange pathways to freedom

- assisted with legal purchases of liberty where possible

- created channels for escape that were never traced back to him

Over roughly three years, multiple enslaved people gained their freedom or successfully fled, aided by strategies that bore Samuel’s quiet design.

By 1854, the official paper trail around him stops.

Rumors say he:

- joined hidden communities in the swamps

- moved north

- or continued working with escape networks until the Civil War broke slavery apart

All of these stories share one point:

He was never defeated.

XVI. A Story the South Tried to Silence

The clearing where the last match took place was swallowed again by the swamp.

Documents were burned.

Newspapers said nothing.

Planters denied the fights had ever occurred.

Still, fragments survived:

- entries from Marshand’s journal

- letters between plantation families

- interviews collected in the 1930s by the Federal Writers’ Project

- oral histories passed down through generations

One interviewee—the granddaughter of a woman enslaved near Opelousas—summed up his true impact:

“His real victory wasn’t in the ring.

It was the people he helped.”

Conclusion: A Man the System Couldn’t Break

The man we call the Bayou Giant—Samuel—was never supposed to leave a trace in history.

His matches were never meant to be public knowledge.

His resistance was never meant to be acknowledged.

His humanity was never meant to be remembered.

Yet it survived.

He stepped into 37 forced fights because he had no real choice.

Many of his opponents did not survive those matches—not through his desire, but through a system that weaponized human bodies for sport and profit.

What Samuel did with that terrible role is what makes his story matter:

He turned coerced violence into a form of resistance—channeling his position into opportunities for others to gain freedom, dignity, and a future.

He remained unbeaten in the ring.

More importantly, he remained unbeaten in spirit.

And that is why his story, nearly erased, still deserves to be told.