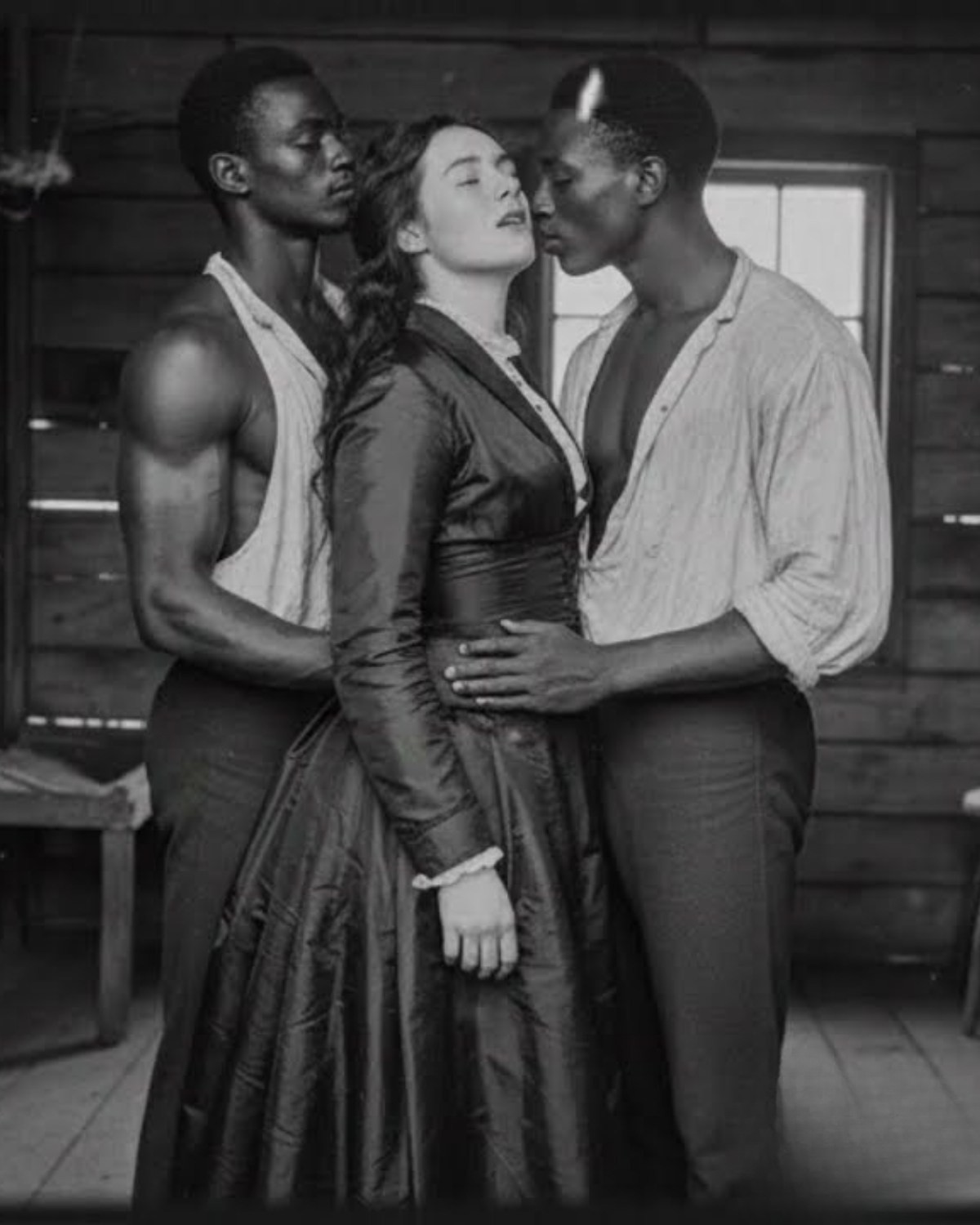

The Society Woman’s Dark Secret… Her Dangerous Obsession With The Men She Publicly Degraded (1847) | HO

PART I — The Quiet Fall of a Charleston Dynasty

When the Ashcraftoft scandal surfaced quietly in November 1847—without newspapers, legal action, or formal accusations—Charleston’s elite reacted as they often did when confronted with something too uncomfortable to acknowledge. They suppressed it. They hid it so thoroughly that only fragments remain today: scattered letters, a locked diary, medical notes from 1848, and testimonies collected from formerly enslaved people in the 1930s by the Works Progress Administration.

From these pieces, however, a clearer portrait appears—not only of one woman’s mental collapse but of a social hierarchy whose contradictions contributed directly to her downfall. This is a story about power, the misuse of that power, the quiet harm built into slavery, and the unexpected ways that harm could turn against those who believed themselves protected.

At the center was Levvenia Bowmont Ashcraftoft, born in 1810 into a respected Charleston family. Educated in Savannah finishing schools, fluent in French, skilled in the decorative arts expected of upper-class women, she married into the Ashcraftoft estate at 23. The marriage united two long-standing families: the Bowmonts with military prestige, and the Ashcraftofts with a large 1,200-acre plantation on the Cooper River.

Local newspapers described her as elegant and poised. Her entrances at balls were talked about; her opinions on fashion circulated among the city’s wives. Publicly, her influence was secure.

Privately, those near her sensed something more. A cousin wrote in 1840 that there was “a hardness beneath the elegance,” suggesting she observed not to understand but to control. A fellow member of a women’s club later recalled her as someone who required everything around her to remain perfectly arranged—and would force it if necessary. These hints would later take on darker meaning.

Ashcraftoft Manor served not only as a home but as a stage she managed carefully. Built in 1798, the large house, decorated with imported furniture and a grand ballroom of Venetian mirrors, was the setting for her social performances. Every detail of her gatherings was choreographed: flower arrangements, tea service by enslaved workers, even the timing of her appearances on the staircase.

Behind this display stood the plantation’s reality—127 enslaved people whose labor made such refinement possible.

Unlike her husband, Theodore, who focused on finances, Levvenia personally oversaw domestic operations. She demanded exact standards: how linens were folded, how servants stood, how dishes were served. To visitors she seemed efficient; to the enslaved staff she was unpredictable and severe.

A former house servant described her in 1937 as “quiet cold”—a person who rarely raised her voice but made even small mistakes costly. She preferred punishments that embarrassed rather than injured: forcing someone to stand holding a tray, or repeat a task endlessly under her observation. There were other incidents, remembered only in whispers, suggesting deeper cruelty.

Even with this, few could foresee the extreme direction her life would later take.

In April 1839, during an early heatwave, Levvenia made a decision that would ultimately lead to her ruin. She ordered that Grace, a 38-year-old enslaved woman, be separated from her sons Elijah and Nathaniel and sold away from the estate. Plantation records called it “routine asset redistribution,” but diaries and oral accounts show it was driven by personal judgment.

Grace was respected by the enslaved community, and her sons—secretly literate—were steady, capable, and known for their quiet dignity. They were not rebellious. Their confidence, however, irritated Levvenia. In a note to her husband, she wrote that their pride “must be broken.”

Elijah was sent to a harsh Alabama plantation known for deadly land-clearing operations. Nathaniel was sent to Mississippi, into a household known for strict discipline. Grace pleaded to be sold in their place; her voice gave out from begging. Levvenia refused.

Years later Elijah said that something in him “turned cold” when they were taken from their mother. Grace died five years later during a cholera outbreak, her last words expressing belief that her sons would return and “make it right.”

In Alabama, Elijah endured years of punishing labor, poor food, and frequent illness, but he learned valuable knowledge from an older woman from Haiti who practiced traditional medicine. Nathaniel, in Mississippi, was exposed to the hidden problems of wealthy households—domestic conflict, misuse of medications, financial trouble, secrets maintained at all costs.

Separately, both brothers survived. Both longed to return. And by chance, a trader eventually purchased each of them and brought them back to Charleston. Their reunion in the holding yard lasted only three days, but in that time they formed a plan: return to Ashcraftoft Manor, gain Levvenia’s trust, and dismantle the world she had used to destroy their family.

They did return in August 1847, purchased by Theodore to replace aging house staff. Levvenia did not recognize them. To her, the enslaved were interchangeable. She simply remarked that they “look acceptable.”

It was the last moment she held unquestioned power over them.

Charleston society long whispered about the emotional isolation of planter wives—women who lived in rural estates with distant husbands and limited outlets. Yet discussions always avoided the more uncomfortable issue: situations where mistresses secretly crossed boundaries of conduct and abused the imbalance of power in the household.

Historical evidence shows this occurred more often than openly acknowledged. Levvenia was among the women who carried such hidden conflicts.

Elijah discovered this in September 1847 when he overheard an incident in the barn between Levvenia and a younger enslaved man. His later testimony avoided explicit detail but made clear that she had exploited her position.

The brothers did not react immediately. They watched, waited, and soon understood: her long-hidden misconduct was the weakness that could eventually bring down an entire dynasty.

PART II — The Psychological Unraveling of Levvenia Ashcraftoft

Although autumn 1847 appeared routine at Ashcraftoft Manor, neighbors began noticing shifts in Levvenia’s behavior. Diaries from the time describe her as tense, easily agitated, and erratic in conversation.

Sarah Rhett Laurens wrote that Levvenia seemed excessively fatigued and spoke with an intensity that unsettled guests. Agnes Pinckney noted that she constantly looked troubled, as if battling an inward anxiety she could not control.

The brothers’ plan was slow and methodical. Rather than confront her, they intended to let her expose herself. Their strategy rested on three steps: attract her attention, create her dependency, and allow her own actions to reveal her misconduct.

Nathaniel understood the emotional emptiness common among neglected planter wives. Elijah understood fear and how to use silence as a weapon.

Gradually, Levvenia’s attention fixed on Elijah. Small interactions grew into patterns: unnecessary touches, dismissing other servants when he appeared, requesting him by name for trivial tasks. Her husband noticed none of this; Nathaniel noticed everything.

Elijah’s calm, restrained demeanor drew her further in. Nathaniel later said: “She punishes what she fears and desires what she can’t control.”

The pivotal moment came on October 3, when she replaced Nathaniel with Elijah in the conservatory. What happened there remains unclear, but it marked a boundary crossed. Elijah later said he allowed her to believe she had power, knowing that belief would destabilize her over time.

From then on, her behavior escalated: unnecessary errands, sudden claims of faintness, irregular requests disrupting the household schedule. Staff logs recorded puzzling changes. Servants whispered that she paced the halls at night, wringing her hands and muttering.

Nathaniel instructed Elijah to maintain a delicate balance—just enough openness to keep her attached, just enough restraint to keep her unsettled. It was dangerous, but it worked.

On October 19, Levvenia wrote in her diary that Elijah’s silence “provokes chaos” in her and that she sought his presence even as she despised the effect he had on her. This was fixation, not affection.

By late October, she was struggling to maintain her public image. She delivered cutting remarks at a dinner, appeared disheveled at church, dropped her prayer book with shaking hands, and made comments about “false virtue” that shocked attendants.

On November 11, during a storm that kept Theodore in Charleston overnight, she summoned Elijah. What happened left her trembling on her dressing room floor. From that point, she plunged into paranoia—believing the enslaved staff watched her, believing Elijah held power over her, believing exposure would destroy her life.

Her diary entries became increasingly frantic. By November 24, she wrote: “If Theodore ever learned what I have done—God preserve me.”

She did not know the brothers intended exactly that.

Sansar refers to domestic conflicts between spouses, but such conflicts should never unfold in front of a child. In one case, constant arguments contributed to the child later falling into harmful dependency, illustrating how unspoken tensions can silently shape a young life.

PART III — Collapse, Exposure, and the Erased Dynasty

By late November 1847, her deterioration became visible even to those outside the manor. Her smiles appeared strained, her posture stiff, her speech disrupted by pauses. Inside the manor, according to later accounts, she had lost control of her behavior and authority.

The brothers began the final phase of their plan.

Nathaniel understood that her greatest fear was not her actions—it was discovery. Plantation society placed white women on a pedestal of moral purity. A mistress exposed for unacceptable conduct toward enslaved men faced ruin: social exile, marital collapse, possibly confinement.

The brothers never issued threats. They allowed her imagination to supply them. Elijah avoided her gaze in public but lingered in private. Nathaniel altered minor tasks to unsettle her. Servants whispered within earshot.

A maid said she jumped at every sound and appeared sleepless. The psychological tension she had created closed in around her.

On November 28, she asked Elijah to bring an account ledger to the upstairs study. The encounter left her disheveled and panicked. Elijah left composed. She paced halls muttering, then wrote in her diary that she feared Elijah might “use her weakness” against her.

The brothers began gathering evidence: Nathaniel uncovered financial inconsistencies in Theodore’s records; Elijah collected notes, torn diary pages, and objects linking Levvenia to her misconduct. Hidden resentment among servants helped corroborate the timeline.

By early December, the brothers held enough to ruin the estate’s reputation.

Charleston’s December gala provided the perfect moment. Levvenia prepared her most elaborate gown, determined to appear composed. Before she could leave, Theodore found a sealed envelope containing fragments of her distressed writings, witness descriptions, and household inconsistencies.

Their confrontation was loud enough for neighbors to hear. Nonetheless, Theodore insisted they attend the gala.

At the event, Levvenia struggled to maintain composure. When speaking with Judge Hartwell’s wife, she blurted: “A woman can only carry so much shame before it spills over.” The room froze.

She walked into the center of the ballroom with a distressed expression. Guests later described her as “hunted.” She spoke in fragmented phrases about deception, guilt, and observing eyes. She named no one, but no one needed clarity.

Theodore removed her, but rumors were already forming.

Back at home she suffered a full breakdown—tearing down drapes, breaking objects, accusing staff of spying, accusing Elijah of influencing her, and accusing Theodore of abandoning her. Servants recalled her shouting that someone “held her secrets.”

By dawn she locked herself in her dressing room. When Theodore forced the door, she lay trembling beside half-burned diary pages. One fragment read: “E. is a danger. I have given him weapons.”

Rumors spread instantly: inappropriate conduct in the household, mental collapse, financial instability. The brothers did not spread these rumors. They allowed silence and suggestion to do the work.

Within days, Theodore transferred her to Mount Hope Sanitarium in Columbia, where she stayed thirteen months. Her diagnosis cited severe melancholia and agitation. Visitors said she paced halls repeating: “I should never have wanted what I wanted.”

While she remained institutionalized, the brothers escaped north with the help of Black sailors. Theodore, humiliated and burdened by debt, sold portions of the estate. By the time Levvenia returned in 1849—quiet and confused—the dynasty was already broken.

She lived privately until her death in 1856. Her obituary described her only as a woman with “refined sensibilities” who suffered long from “nervous ailments.” Her journals were sealed, and her story avoided by her descendants for generations.

Elijah and Nathaniel reappeared in Philadelphia records in 1852 under new names, working as carpenters. They married, raised families, and lived long lives. In 1937 Elijah said: “She broke our family first. Then she found someone she couldn’t control, and that’s what ruined her.”

Historians see broader meaning in the Ashcraftoft case. It revealed contradictions in Southern ideals of womanhood, showed how fragile planter society was beneath its polished exterior, and demonstrated the agency of enslaved people who used observation and truth—not violence—to dismantle the power of those who harmed them.

Levvenia’s fall was not simply the story of a powerful woman brought low by two men she once commanded. It was the story of a woman undone by her own choices—her mistreatment of others, her misuse of authority, and the illusions that convinced her she was untouchable.

A dynasty built on domination eventually collapsed under the weight of its own contradictions. And two brothers, once powerless boys torn from their mother, walked away free.