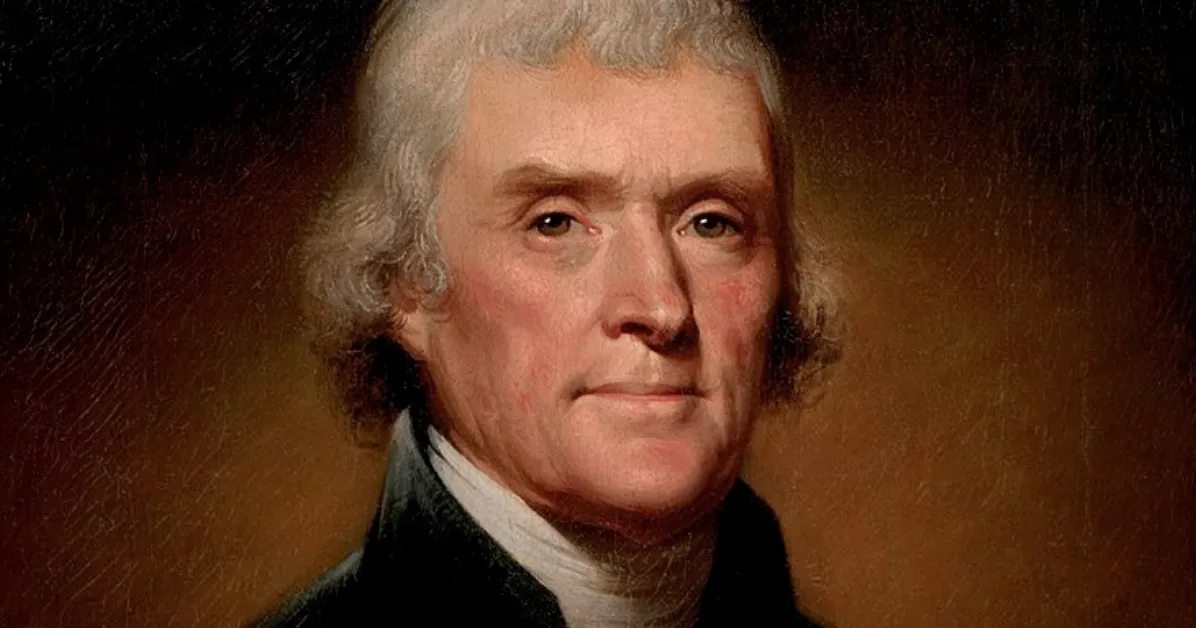

Thomas Jefferson is often remembered first as the principal author of the Declaration of Independence and the third president of the United States—a man who wrote that “all men are created equal” and framed himself as a champion of liberty. Yet across his lifetime, Jefferson enslaved more than 600 people. Among them was Sally Hemings, the woman with whom he is now widely understood to have had a long-term intimate relationship and several children, all while she remained legally his property.

For nearly two centuries, this relationship has stood at the heart of a national contradiction. Jefferson spoke eloquently of natural rights, but those ideas did not extend to the people whose labor sustained his wealth. As biographer John Boles has observed, the same man who gave the nation some of its most compelling language on freedom did not defend the freedom of the people whose lives would have been most transformed by it. Historian Lonnie Bunch has called this the fundamental paradox of the new republic: the humanitarian ideals of the founding documents were not available to everyone.

The Jefferson–Hemings story illustrates this paradox at the most personal level. It is about power, family, race, and the complicated ways in which freedom and bondage were intertwined at Monticello.

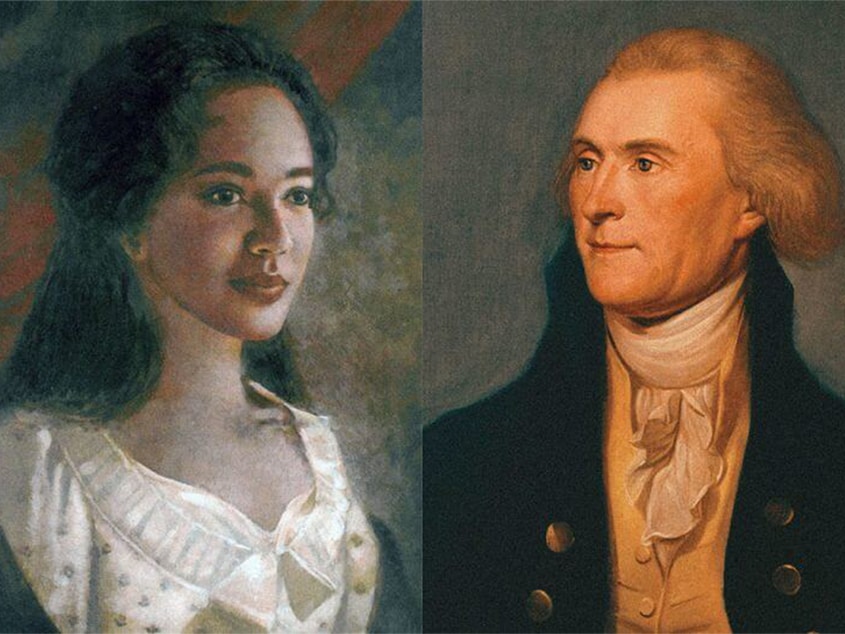

Who Was Sally Hemings?

Sally Hemings was born around 1773 on the Virginia plantation of John Wayles, Jefferson’s father-in-law. Her mother, Elizabeth Hemings, was an enslaved woman; her father was Wayles himself. That made Sally the half-sister of Jefferson’s wife, Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson.

When Wayles died, Jefferson inherited a large number of enslaved people—about 135 men, women, and children—including the Hemings family. Sally arrived at Monticello as a young child, growing up within a household where some of the people around her were both relatives and property.

From a young age, she served in the main house rather than the fields, working in domestic roles and acting as a companion to Jefferson’s daughters. Her duties would later include caring for Jefferson’s private rooms, managing his wardrobe, and helping with sewing and childcare.

Very little about Hemings comes to us in her own words. No letters or written records from her have survived, and it is unclear whether she could read or write. Contemporary descriptions focus on her appearance, noting her long, straight dark hair and beauty. In many ways, her life must be reconstructed indirectly, through the records left by others and the testimony of her children.

Paris: A Different World—and a Turning Point

In the 1780s, Jefferson was appointed U.S. minister to France. Two years after he took up the post, he sent for his young daughter Maria to join him, and fourteen-year-old Sally Hemings was chosen to accompany her.

Her older brother James Hemings had already been taken to Paris to train as a French chef. In France, both siblings encountered a very different legal and social environment. Slavery was effectively illegal there, and enslaved people brought from abroad could, at least in principle, claim their freedom.

Sally enjoyed more latitude in Paris than she likely had in Virginia. She learned some French and moved in a world where Black people had a somewhat different status than in the slaveholding South. It is during this Paris period that historians believe her intimate relationship with Jefferson began—she was a teenager; he was a middle-aged widower.

Crucially, when Jefferson prepared to return to Virginia in 1789, Hemings had a real, if limited, option: she could have attempted to remain in France as a free person. Instead, according to her son Madison Hemings’s later memoir, she negotiated with Jefferson.

Negotiating for Her Children’s Freedom

Madison Hemings, writing decades later in Life Among the Lowly, No. 1, described his mother as using this moment to secure a measure of protection for her future children. He recalled that she refused to sail home until Jefferson promised her “extraordinary privileges” and pledged that any children born to her in Virginia would be freed at age twenty-one.

Pulitzer Prize–winning historian Annette Gordon-Reed, in The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family, emphasizes how unusual this was. Hemings, still a teenager and enslaved, was operating in a narrow space of leverage: she could walk away in France, but with uncertain prospects. Instead of using that possibility solely for herself, she turned it into a negotiation that focused on her children’s eventual freedom.

When she returned to Monticello, Hemings was pregnant. The first child she bore after coming back to Virginia did not survive. Over time, she had at least five more children while enslaved at Monticello. Four lived to adulthood: Beverly, Harriet, Madison, and Eston.

Did Jefferson Father Hemings’ Children?

Rumors about Jefferson and an enslaved woman circulated even during his lifetime and were weaponized in political battles. For generations, family stories, local accounts, and circumstantial evidence pointed toward Jefferson’s paternity of Hemings’s children, but many historians and Jefferson defenders resisted that conclusion.

The debate shifted dramatically in the late 1990s. A 1998 DNA study compared genetic material from male-line descendants of Eston Hemings with that of Jefferson male-line descendants. The results showed a match to the Jefferson family. The study could not specify Thomas Jefferson personally, but when combined with documentary evidence, it strongly supported that conclusion.

In 2000, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello issued a report describing the question of paternity as a “settled historical matter”: the evidence overwhelmingly supported that Thomas Jefferson was the father of Sally Hemings’s children.

Monticello scholars and Gordon-Reed’s research highlight several key points:

- Hemings’s known children were the only enslaved family Jefferson ever systematically freed or allowed to leave without pursuit.

- They were described as very light-skinned, and several observers remarked that they resembled Jefferson.

- Records show that Hemings conceived only when Jefferson was present at Monticello. Over nearly two decades, there are no conceptions that occurred while he was away from the plantation.

Taken together—DNA data, timing, oral history, and behavior—these factors underpin the current historical consensus: Jefferson almost certainly fathered Hemings’s children.

Life Inside Monticello: Privilege Within Bondage

Within the Monticello system, Hemings and her children occupied a complicated position. They remained enslaved for most of their lives there, yet their assignments and treatment differed from those of many others on the plantation.

Hemings appears to have been shielded from field labor. According to Madison Hemings, her primary duties involved Jefferson’s private spaces and care for his children, along with light domestic work such as sewing. She had more regular contact with the family in the main house, though always within the limits and power imbalance of enslavement.

Her children were also spared field work. Instead, they were trained in skilled trades—carpentry, music, and domestic service—that could support them if they eventually entered free society. Madison remembered, however, that Jefferson did not publicly acknowledge them as his sons and daughter, nor show overt parental affection. “My brothers, sister Harriet and myself were used alike…” he wrote. “I was put to the carpenter trade.”

Hemings’s situation illustrates a harsh reality of the era: even when enslaved people had somewhat better conditions or closer domestic roles, their basic status remained unchanged. Their time, labor, and bodies were still under someone else’s control.

Freedom, Departure, and a Legacy of Silence

Jefferson died in 1826, heavily in debt—his obligations amounted to the equivalent of over a million dollars in modern terms. Those debts drove the sale of much of his estate. In 1827, newspapers advertised Monticello and about 130 enslaved people for auction. Nearly one hundred human beings were sold over several days on the very grounds where Jefferson had written about liberty.

For the Hemings children, however, the end of Jefferson’s life marked a partial opening. Madison and Eston were formally freed in Jefferson’s will. Beverly and Harriet had already been allowed to leave Monticello quietly a few years earlier without being pursued as fugitives. According to Madison’s later account, both passed into white society, choosing not to identify publicly as Black or as Jefferson’s children.

Sally Hemings herself was not officially emancipated in Jefferson’s will. However, Jefferson’s daughter Martha and her family allowed Hemings to live in Charlottesville with her sons as a free woman in practice, if not on paper. She spent her final years there, out of the plantation system that had shaped most of her life.

The Jefferson–Hemings descendants and scholars continue to grapple with what this story means. On one level, it is the history of a specific family: a woman born enslaved, related to the white family that owned her, who negotiated for her children’s future and lived in a long-term relationship with the man who legally controlled her life.

On another level, it is a window into the founding era’s deepest contradictions—a reminder that the language of universal rights emerged from a society where exploitation and coercion were written into law, and where even the most famous advocates of liberty often failed to extend those ideals to the people closest to them.

Today, Monticello presents the stories of Jefferson and Hemings side by side, acknowledging not only the architecture and ideas of the estate, but also the lives and labor of the people who made it function. In doing so, it invites visitors and readers to confront the full complexity of the early United States: its aspirations, its injustices, and the human lives that existed at their intersection.