A Discovery From the Peatlands

In 1922, in the quiet landscape of northern Germany, peat cutters stumbled upon a discovery that would unsettle archaeologists for generations: the remains of a child preserved in a bog. Known today as the Kayhausen Boy, this seven-year-old’s body dates to around 300–400 BCE, placing him firmly within the Iron Age.

Northern Europe’s bogs are famous for their preservative qualities. Their unique chemistry, low oxygen levels, and acidic waters can mummify human remains for thousands of years. From the Tollund Man in Denmark to the Grauballe Man, these so-called “bog bodies” provide extraordinary glimpses into the lives—and deaths—of ancient Europeans.

But the Kayhausen Boy is different. His remains are not simply remarkable for their preservation, but for the disturbing clues they reveal about his final moments.

The Clues in the Bogs

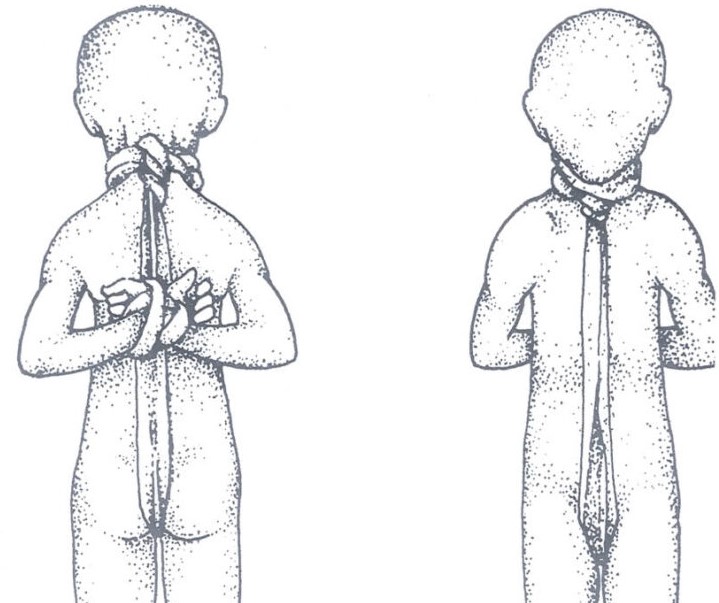

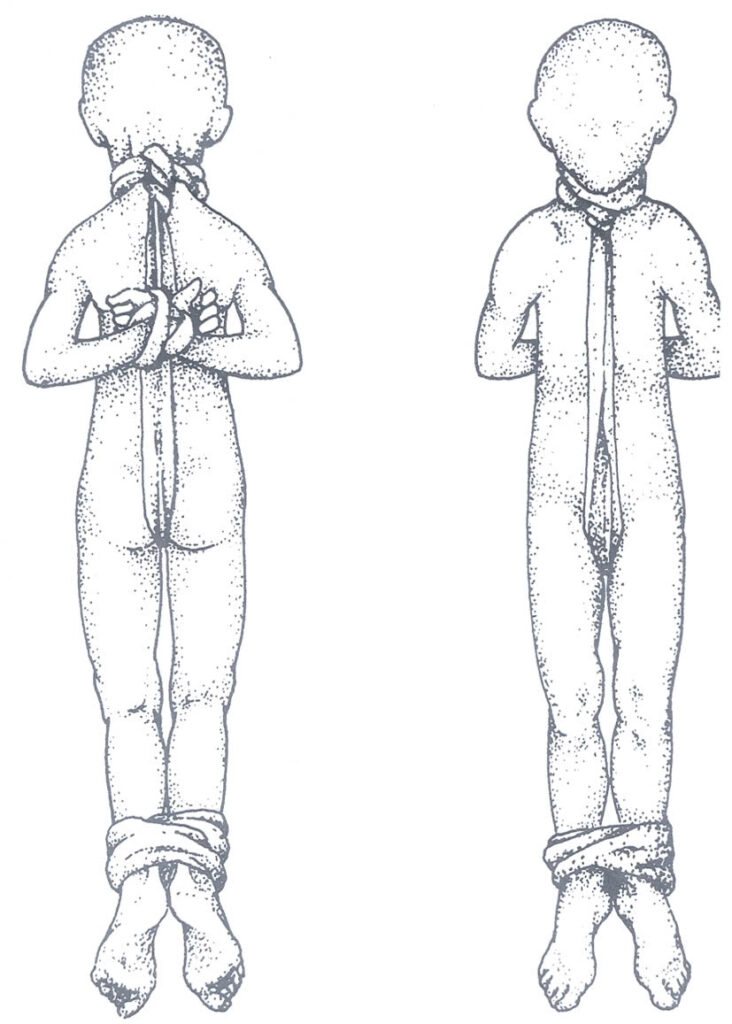

The boy was found with his arms and feet bound by cloth strips, an indication that his restraint was deliberate rather than accidental. Unlike accidental drownings, this suggests intention—someone placed him in the bog.

Forensic examination uncovered evidence of multiple stab wounds to his body, including three to the neck. A wound on his left arm indicates that he may have attempted to defend himself. The combination of restraint and injury suggests that the Kayhausen Boy did not meet a natural death.

For archaeologists, these details raise a central question: was this child’s death a ritual sacrifice or the result of interpersonal violence?

Ritual Sacrifice in the Iron Age

One interpretation aligns the case with ritual practices documented in Iron Age Europe. Many ancient communities considered bogs to be liminal spaces—thresholds between the human and spiritual realms. As such, they were often chosen as sites for offerings, whether of weapons, valuable objects, or, at times, humans.

Archaeological finds show that during times of crisis—crop failures, drought, or conflict—Iron Age people may have turned to sacrificial rituals in hopes of appeasing deities. The Kayhausen Boy’s bindings could represent a ceremonial act, preparing him as an offering.

The targeted wounds to the neck are consistent with methods seen in other bog bodies believed to have been ritually killed. If this was the case, the child may have been selected as a symbolic representative of his community, offered to ensure survival or prosperity.

The Case for Violence or Punishment

An alternative explanation is less ritualistic and more personal. The boy’s defensive wound suggests he resisted his attacker. This detail complicates the sacrifice theory, where victims might be incapacitated or killed swiftly.

Some archaeologists argue that the child could have been the victim of punishment within his community. The Iron Age was marked by social hierarchies, conflicts, and harsh systems of justice. A child might have been targeted for reasons we may never fully understand: social stigma, accusations, or interpersonal disputes.

Another possibility is concealment. Binding the body and leaving it in the bog may have been an attempt to hide a crime. Ironically, the bog’s chemistry preserved the evidence instead of erasing it.

Lessons From Other Bog Bodies

To understand the Kayhausen Boy, it is helpful to compare him to other bog discoveries:

-

Tollund Man (Denmark): A man found with a noose around his neck, interpreted as ritual sacrifice.

-

Grauballe Man (Denmark): Discovered with a slit throat, also linked to ceremonial death.

-

Windeby Girl (Germany): Originally thought to be a punished adulteress, but later studies showed the individual was a teenage boy who may have died by natural causes.

These cases reveal how interpretations can shift with new forensic technology. What was once seen as punishment may later be understood as ritual—or vice versa. The Kayhausen Boy remains within this spectrum of uncertainty.

Advances in Forensic Archaeology

Modern techniques continue to shed light on bog bodies. CT scans, isotope analysis, and microscopic examinations reveal details about diet, health, and cause of death. For the Kayhausen Boy, future studies may clarify his ancestry, daily life, and perhaps the precise sequence of his final moments.

Stable isotope analysis, for example, could show whether he was local to the region or brought from elsewhere, while textile studies of his bindings may reveal cultural patterns. Such work underscores how each new generation of science can reframe ancient mysteries.

Symbolism and Cultural Meaning

Whether the Kayhausen Boy was sacrificed to gods or slain in violence, his death reflects the complex relationship between Iron Age societies and mortality. Children, often symbols of innocence, rarely appear in the archaeological record as victims of ritual. His case forces us to confront difficult questions about how ancient communities balanced spirituality, justice, and cruelty.

At the same time, his preservation allows modern societies to engage with the past not only through artifacts but through individual human stories. The Kayhausen Boy was not an anonymous statistic of prehistory; he was a child who lived, resisted, and died, leaving behind evidence of his humanity.

A Mystery That Endures

More than a century after his discovery, the Kayhausen Boy continues to provoke debate. Was he a sacred offering, a punished transgressor, or simply a victim of interpersonal violence? The answer remains elusive.

What is clear is that his story adds to our understanding of the Iron Age as a time of ritual intensity, social complexity, and human vulnerability. Each theory—sacrifice or violence—reveals a different side of ancient life.

Conclusion: A Voice From the Past

The Kayhausen Boy stands as both an archaeological treasure and a sobering reminder of humanity’s past. His small body, preserved by chance in a German bog, bridges millennia to remind us of the darker aspects of history.

As science progresses, perhaps new discoveries will one day reveal more about his short life and tragic end. Until then, his presence challenges us to reflect on the fine line between ritual, justice, and violence in human societies—both ancient and modern.