In the heart of Mexico City, archaeologists have unearthed a chilling yet extraordinary structure that has stunned the world. Known as the Huey Tzompantli, this Aztec skull tower reveals the scale of ritual sacrifice in the empire’s capital, Tenochtitlán.

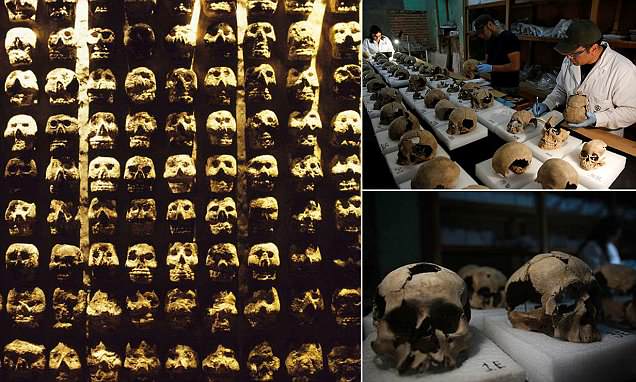

The discovery—originally made in 2015 but expanded in later excavations—showcases over 600 human skulls meticulously arranged and cemented together. Far from being a morbid curiosity, the tower represents a window into the religion, politics, and cosmology of the Aztec world.

What Is a Tzompantli?

The word tzompantli comes from the Nahuatl language, meaning “skull rack.” Such structures were used by Mesoamerican cultures to display the skulls of sacrificial victims or captured warriors.

The Huey Tzompantli (“Great Skull Rack”) was the most important of these monuments in Tenochtitlán. Spanish conquistadors, including Hernán Cortés, described them in awe and horror during the conquest of 1521. Until the recent excavation, many scholars debated whether the accounts were exaggerated. The archaeology, however, confirms their existence.

A Grim Legacy of Scale

So far, archaeologists have documented 603 skulls in the Huey Tzompantli. The cylindrical structure, measuring more than 16 feet in diameter, was built from lime and sand mortar. The skulls were arranged in rows, forming a circular wall of bone.

Excavations revealed:

-

Skulls of men, women, and children, challenging earlier beliefs that only male warriors were sacrificed.

-

Evidence of ritual placement, with skulls treated not as refuse but as sacred offerings.

-

Construction dating between 1486 and 1502, during the reigns of rulers Ahuízotl and Moctezuma II.

The presence of women and children among the remains has raised new questions about the social and religious functions of the tower.

Ritual Sacrifice and the Aztec Cosmos

For the Aztecs, ritual sacrifice was not cruelty but cosmic necessity. They believed the gods required nourishment to maintain the balance of the universe—particularly the sun, which demanded constant energy to rise each day.

The skull tower symbolized:

-

The cycle of life and death, where human offerings ensured agricultural fertility and cosmic order.

-

Power and prestige, projecting the dominance of the Aztec Empire over rivals.

-

Religious devotion, with skulls transformed into sacred objects or even embodiments of deities.

By constructing the Huey Tzompantli near the Templo Mayor, the main religious center of Tenochtitlán, the Aztecs placed this structure at the symbolic heart of their world.

Historical Accounts and Conquest

Spanish chroniclers were both horrified and fascinated by the skull racks they encountered in 1521. Bernal Díaz del Castillo described thousands of skulls displayed in racks near the Templo Mayor. While numbers may have been exaggerated, the archaeology confirms that such towers existed on a massive scale.

Following the conquest, Spanish forces destroyed most of the structures, seeking to erase symbols of Aztec religion. The Huey Tzompantli lay hidden for centuries beneath colonial and modern Mexico City, only resurfacing during recent excavations.

Unsettling Revelations

Perhaps the most striking revelation is the diversity of individuals represented in the tower. Among the 119 newly discovered skulls are those of women and children, including three with immature teeth.

This challenges assumptions that only captured warriors were sacrificed. Instead, the evidence suggests that a broader segment of society—including non-combatants—was included in these rituals. The reasons remain debated:

-

Some argue it reflects dedications of entire families or social groups.

-

Others suggest it was part of cosmological offerings, where age and gender diversity symbolized humanity as a whole.

Excavation and Research

The excavation has been led by Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) through its Urban Archaeology Program. The site lies close to the Metropolitan Cathedral, atop the ruins of the Templo Mayor complex.

Archaeologists have carefully documented, stabilized, and studied the remains to preserve them for ongoing research. Every skull contributes data about age, sex, health, and ritual modification, building a clearer picture of Aztec life and death.

Between Faith and Fear

To modern observers, the skull tower evokes horror. But within Aztec culture, it embodied the fusion of faith and fear. The display of skulls was not only a reminder of divine power but also a political message to enemies and subjects: the gods demanded offerings, and the empire had the might to provide them.

This duality—sacred devotion intertwined with state authority—is what makes the Huey Tzompantli so significant. It was not simply an execution site but a ritual monument with profound symbolic meaning.

Why the Discovery Matters Today

The Huey Tzompantli is more than an archaeological marvel. It matters because it:

-

Confirms the accuracy of historical accounts once dismissed as exaggerations.

-

Expands our understanding of Aztec religion and society, including the role of women and children in rituals.

-

Preserves cultural heritage, reminding us of the complexity of pre-Columbian civilizations.

For modern Mexico, it is a reminder of an indigenous past that, though often misunderstood, was rich in meaning and cultural sophistication.

Conclusion: The Tower That Speaks Across Centuries

The Huey Tzompantli skull tower is a rare monument where history, archaeology, and myth converge. Its macabre magnificence forces us to confront difficult truths about the human past: that devotion can inspire acts both awe-inspiring and terrifying, and that cultures express their deepest values in ways that may unsettle outsiders.

As excavations continue, the tower will yield more insights into Aztec cosmology and society. But even now, standing beneath Mexico City’s cathedral, it reminds us of the enduring dialogue between life, death, faith, and power in human history.