High in the mist-covered highlands of Ethiopia, where stone churches are carved from living rock and monasteries cling to cliffs, a Christian tradition has been quietly preserved for more than 1,500 years.

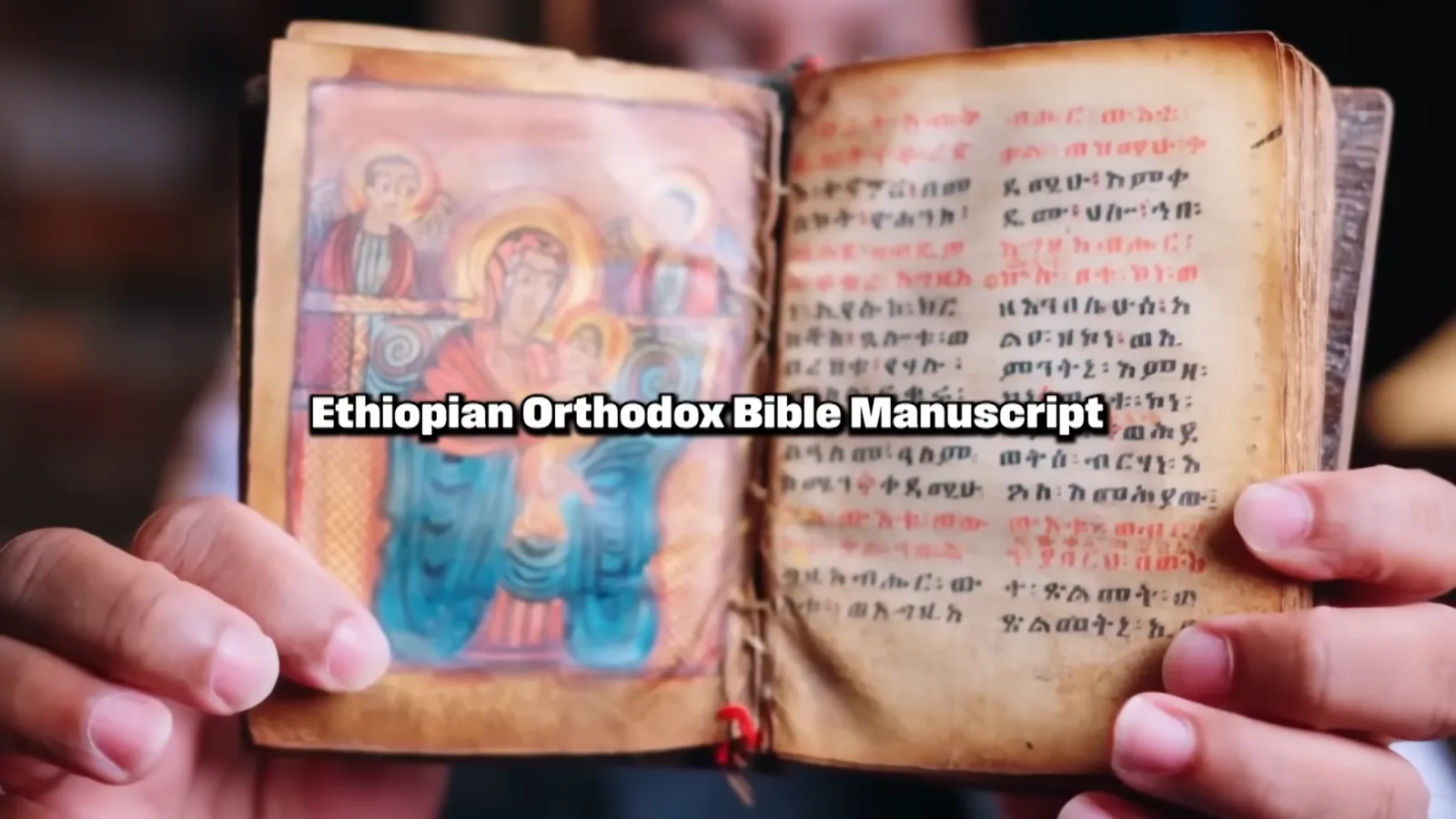

At the heart of this tradition is a remarkable collection of handwritten manuscripts in Ge’ez, the ancient liturgical language of Ethiopia. Some of these codices are bound in leather, written on parchment, and copied by monks who devoted their entire lives to prayer, fasting, and the careful transmission of sacred texts.

For many in the West, “the Bible” means the familiar 66-book Protestant canon or the slightly larger Catholic and Orthodox collections. But in Ethiopia, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church preserves one of the broadest biblical canons in the Christian world—traditionally counted as 81 books. This expanded canon has led some popular writers to describe it as containing “lost” or “forgotten” words of Jesus and early Christianity.

The reality is more nuanced—and, in many ways, more interesting.

A Bible That Looks Different From the Western One

The Ethiopian canon includes the books known across global Christianity—Genesis, the Gospels, the Psalms, the letters of Paul—but it also preserves texts long considered “apocryphal” or “extra-canonical” elsewhere. Among them are:

-

1 Enoch – an ancient Jewish work about heavenly visions and judgment

-

Jubilees – a retelling of Genesis and part of Exodus with its own calendar and emphases

-

The Shepherd of Hermas – an early Christian text of visions and parables

-

Various church orders and “covenant” texts that blend law, liturgy, and moral teaching

These writings do not “replace” the New Testament Gospels, but they sit alongside them in Ethiopian tradition, shaping prayer, theology, and imagination in ways that differ from Western Christianity.

Because some of these texts are preserved only or primarily in Ge’ez, Ethiopia has become a crucial archive for scholars trying to reconstruct the diversity of early Christian belief.

Ge’ez Manuscripts and the “Words of the Risen Christ”

Stories often circulate online about an “Ethiopian Bible” that contains secret sayings of Jesus after the resurrection—words supposedly hidden from the rest of the world. There is a grain of truth behind that, but it needs careful framing.

Ethiopian Christianity, like many ancient traditions, preserves:

-

Homilies and sermons attributed to Christ

-

Mystical reflections on the forty days after the resurrection

-

Liturgical prayers and dialogues where Jesus “speaks” to his followers

Some of these appear in texts referred to as “Book of the Covenant” or other ecclesiastical collections, which combine biblical quotations, church rules, and spiritual teaching. In them, Jesus is portrayed as emphasizing:

-

The heart as the true “temple” of God

-

Love, mercy, and humility as the core of divine law

-

Warnings against corruption, greed, and using religion for power

Rather than being treated as literal, stenographic transcripts of new sayings, these passages are generally understood by scholars as later theological expansions: early Christian communities and later church writers meditating on what the risen Jesus might say about their struggles, injustices, and hopes.

To the faithful within the Ethiopian Church, these texts are not just curiosities. They form part of a living tradition of how Christ’s voice is heard through Scripture, liturgy, and centuries of spiritual reflection.

Resurrection “Reimagined”—Or Deepened?

In Western Bibles, the resurrection narratives are relatively brief:

-

Jesus appears to the women at the tomb

-

He meets the disciples in locked rooms and on the road

-

He speaks, blesses, and then ascends

Ethiopian liturgical and extra-canonical texts often linger on these forty days, contemplating them in detailed, symbolic language. Rather than altering the core claim—that Jesus rose from the dead—they expand it with:

-

Extended discourses on the nature of the soul

-

Teachings about inner transformation and “spiritual resurrection”

-

Imagery of light, fire, and awakening

Some texts speak of humans as “wearing” the body like clothing and describe death as changing garments rather than ceasing to exist. Others picture every person carrying inner “fires” of good and evil choices, a poetic way of talking about conscience and spiritual growth.

These themes don’t erase the resurrection event; they reinterpret its meaning for daily life, turning it from a single moment in history into an ongoing call to inner renewal.

Warnings Against Power, Wealth, and Empty Religion

One striking feature of many Ethiopian homilies and church writings is their sharp critique of religious hypocrisy and worldly power.

Passages attributed to Jesus in these traditions—whether literally his words or later paraphrases of his teaching—often emphasize that:

-

Faith is not about impressive buildings or political influence

-

True worship is measured by justice, mercy, and care for the poor

-

Those who use God’s name to gain wealth or status betray the heart of the Gospel

These themes echo the canonical Gospels (“Beware of the scribes…who devour widows’ houses”) but press them further, sometimes applying them implicitly to later ages in which churches became powerful institutions.

For devoted Ethiopian monks, these warnings are not theoretical. Their own lives of fasting, simplicity, and seclusion are partly a response to such teachings: a conscious choice to prioritize spiritual depth over public influence.

Ethiopia’s Unique Christian Story

Ethiopia’s Christian tradition is ancient and unusually continuous:

-

Christianity became deeply rooted there by the 4th century CE, around the same time as in the Roman Empire.

-

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church developed its own liturgy, iconography, and canon, closely linked to both Jewish and early Christian traditions.

-

Ge’ez, now a liturgical language, preserves some texts earlier than their surviving Greek or Latin versions.

Ethiopian tradition also includes powerful legends, such as:

-

The visit of the Queen of Sheba to King Solomon

-

The birth of Menelik I, said to be their son

-

The arrival of the Ark of the Covenant in Axum

Historians distinguish between verifiable facts, strong traditions, and legendary elements—but there is no question that Ethiopia has been a center of Christian thought and practice for over 1,600 years, largely on its own terms.

Faith, Scholarship, and the “Lost Words” Narrative

Modern media often frames Ethiopia’s manuscripts in dramatic terms: “hidden gospels,” “lost bibles,” or “forbidden words of Jesus.” These phrases attract attention, but they can be misleading.

A more responsible way to describe the situation is this:

-

Ethiopia preserves a wider early Christian library than many Western traditions.

-

Some texts contain sayings attributed to Jesus, visions, and teachings not included in the standard Western canon.

-

Scholars debate their dates, authorship, and relationship to the earliest Christian communities.

-

For Ethiopian believers, these writings are part of a living spiritual tradition, not simply historical artifacts.

The question is less “Did the church hide these?” and more “How did different Christian communities decide which texts to canonize, which to keep as devotional literature, and which to set aside?”

Why These Manuscripts Matter Today

Even for readers who do not belong to the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, the Ge’ez manuscripts are important because they:

-

Show how diverse early Christian thought really was

-

Preserve voices that emphasize mercy, simplicity, and inner transformation

-

Challenge the assumption that Christianity developed along a single, uniform path through Rome alone

-

Invite fresh reflection on themes like resurrection, justice, and spiritual awakening

For some, the “lost words of Jesus” label is about mystery and suspense. For others, the real treasure lies in something quieter: the faithfulness of communities that copied, read, and prayed these texts across centuries, far from imperial capitals, wars, and doctrinal councils.

A Different Kind of Resurrection

When people speak of “resurrection reimagined” in the context of Ethiopia’s ancient Bible, they are often pointing to this insight:

-

The resurrection is not only an event in the past;

-

It is a pattern of renewal, a call to awaken the “divine spark” within, to turn from injustice to compassion, from empty ritual to living faith.

Whether one accepts Ethiopian extra-canonical traditions as historical records, spiritual poetry, or somewhere in between, they offer a profound message:

That the story of Jesus did not end at the empty tomb.

That generations of believers continued to listen for his voice—in Scripture, in prayer, in the depths of conscience.

And that some of those echoes were written down, in ink and parchment, in a language now read by monks in stone churches above Ethiopian lakes and valleys.

For nearly two millennia, those words have been preserved not as a replacement for the Gospel, but as an invitation to go deeper into it.

In that sense, the most important “lost word” may not be a specific sentence at all—but the reminder that the story of faith is larger, older, and more diverse than many of us ever realized.