In the peaceful Dutch countryside, where the mist drifts low over endless boglands, one of Europe’s most haunting archaeological discoveries came to light. In 1897, near the quiet village of Yde, two peat cutters stumbled upon what first seemed a strange bundle hidden beneath the dark surface of the Stijfveen swamp. But as they unearthed it, the truth revealed itself — a body, startlingly well-preserved, with traces of reddish hair still clinging to the skull. What they had found would go on to puzzle historians, scientists, and storytellers for generations: the Yde Girl, a young victim from two millennia ago whose fate remains one of Europe’s enduring mysteries.

A Discovery That Stopped Time

When the authorities arrived at the scene, they realized the significance of what had been found. The body, that of a teenage girl, was astonishingly intact thanks to the swamp’s natural preservation. Peat bogs — with their cold, oxygen-poor and acidic conditions — can preserve organic matter for thousands of years, creating the eerie phenomenon known as bog bodies.

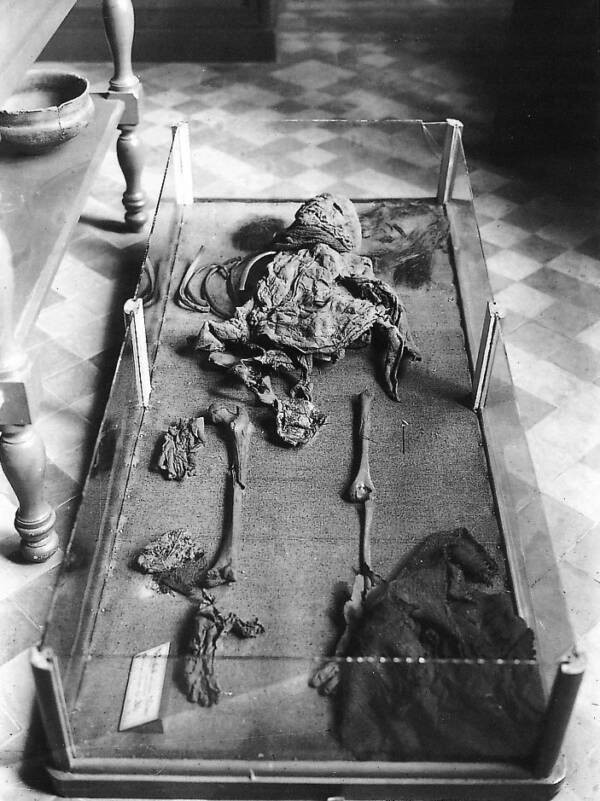

The Yde Girl’s remains, soon transported to the Drents Museum in Assen, offered a chilling glimpse into the past. Around her neck was a woolen cord, tied like a noose. A wound near her head suggested trauma, and her limbs, slightly displaced, hinted at possible postmortem movement. Half her hair had been cut short, while the other half flowed freely — a detail that would inspire both scientific inquiry and mythic speculation.

Clues Written in Her Bones

For decades, researchers could do little more than wonder who she was and why she died. But in the 20th century, with the rise of modern archaeology and forensic science, new light began to pierce the mystery. Radiocarbon dating placed her death between 54 BCE and 128 CE, aligning her life with the late Iron Age — a time when Europe’s tribal societies still practiced complex rituals blending religion, justice, and superstition.

Further analysis revealed that the girl had been about 16 years old at the time of her death. She suffered from scoliosis, a curvature of the spine, and a deformity of the foot that likely caused her to limp. Such conditions, though not fatal, might have set her apart within her community — an element that many later researchers would consider crucial to understanding her story.

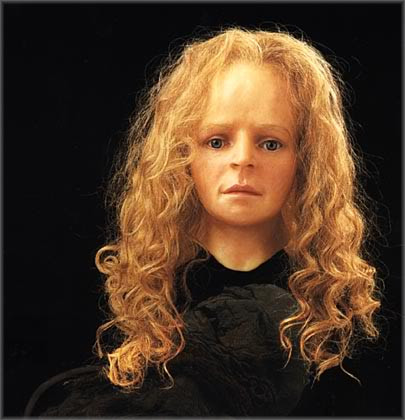

A Face from the Ancient World

In 1992, Professor Richard Neave, a facial reconstruction expert from the University of Manchester, conducted a CT scan of the skull. His reconstruction brought the Yde Girl back to life in haunting detail — a young woman with soft features, a solemn expression, and reddish-blonde hair that gave her an otherworldly presence. The image became iconic, transforming her from an archaeological curiosity into a face that seemed to gaze directly across two thousand years.

Ritual or Retribution?

From the beginning, scholars debated whether the Yde Girl’s death was an act of violence or veneration. Dr. Roy van Beek of Wageningen University proposed two main theories. One suggested that she may have been executed for breaking tribal law — the noose symbolizing a form of punishment. The other, now more widely accepted, interpreted her death as a ritual sacrifice, a solemn offering to the gods that ancient peoples believed governed fertility, harvest, and survival.

The site of her burial, roughly one kilometer from a known Iron Age settlement, seemed deliberate — secluded yet close enough to imply ritual significance. Similar discoveries across Northern Europe — in Denmark, Ireland, and Germany — reveal that bogs often served as sacred boundaries between the living and spiritual worlds, making them powerful sites for ceremonial offerings.

A Tragic Offering to the Gods

In 2019, Dr. van Beek and his colleagues revisited the case using new data and cultural analysis. Their hypothesis suggested that the Yde Girl’s physical differences — her limp, her posture, her distinctive features — may have marked her as special, even sacred. In societies deeply attuned to omens and balance, individuals who appeared “different” were sometimes chosen for ritual sacrifice, believed to embody a connection to the divine.

Her half-shorn hair might symbolize a ritual transformation, representing both life and death, purity and passage. The act of cutting one side of the head was, in some ancient traditions, a sign of dedication — a way of offering part of oneself to the gods.

Echoes of a Lost World

Today, the Yde Girl lies peacefully in the Drents Museum, preserved behind glass yet still whispering stories of an ancient landscape and a vanished belief system. Visitors often describe a sense of awe — and sorrow — when standing before her. Her body, fragile but enduring, bridges the vast distance between modern understanding and prehistoric faith.

Her discovery has also transformed how science perceives bog bodies. Researchers now recognize these remains not as isolated oddities but as part of a broader cultural phenomenon across Iron Age Europe. Each preserved figure — from Denmark’s Tollund Man to Germany’s Windeby Girl — tells a piece of a shared human narrative: one where nature, religion, and mortality intertwined in ways we are only beginning to grasp.

The Enduring Mystery

Despite centuries of study, the true circumstances of the Yde Girl’s death may never be fully known. Was she sacrificed to ensure a good harvest? Punished under tribal law? Or was her death a tragic misunderstanding, frozen forever in peat and time?

What remains undeniable is her legacy. The Yde Girl stands as both an archaeological treasure and a haunting reminder of humanity’s ancient complexities. Her life, though brief, continues to inspire curiosity and compassion, urging us to look deeper — into the soil, the myths, and ourselves.

Over two thousand years later, she still holds her secrets close — a silent witness from an age when the line between the sacred and the human was as thin as the mist over the bogs of Yde.