Ancient Text Challenges Traditional Biblical Narratives

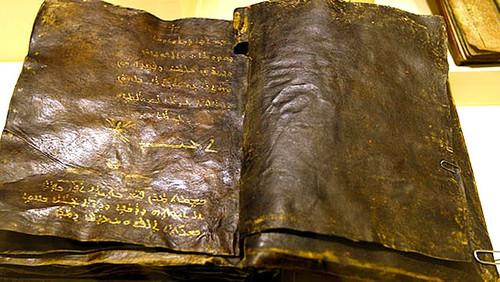

In a quiet museum in Ankara, Turkey, rests a relic that has reignited one of history’s oldest debates — a 1,500-year-old Bible written in Syriac, a dialect closely related to Aramaic, the language spoken by Jesus himself. Its discovery has sparked global fascination and theological controversy, for within its pages lies a version of events that diverges sharply from the accepted Christian narrative.

A Controversial Discovery in Turkey

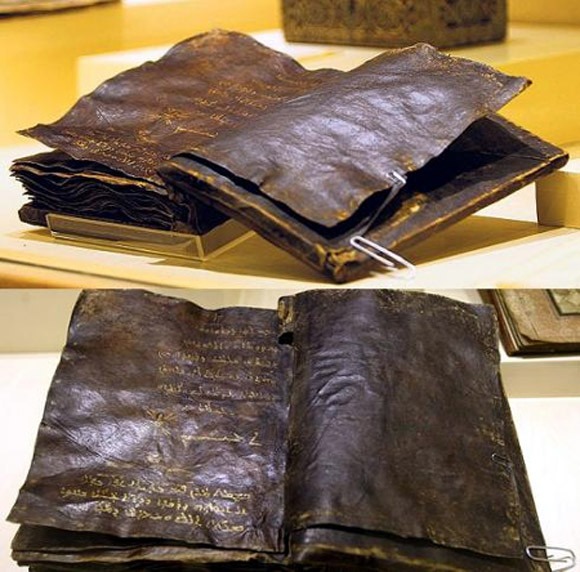

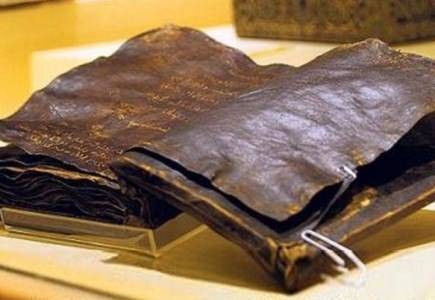

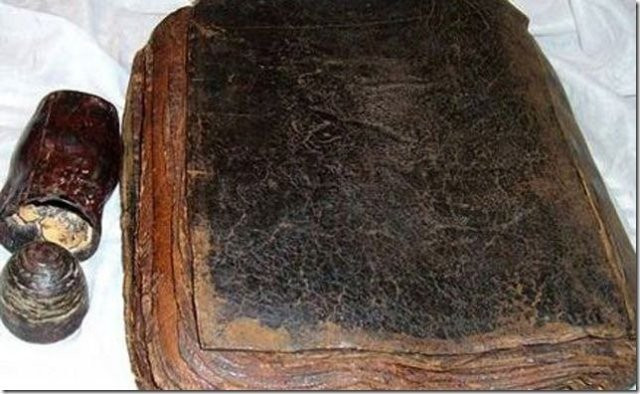

Believed to date between the 5th and 6th centuries, the manuscript was recovered from a smuggling operation in southeastern Turkey and later secured by the nation’s Department of Antiquities. Bound in dark leather and written in gold lettering, the ancient text has been remarkably well preserved — a silent testament to centuries of hidden history.

But it is not its age that has stirred such intense debate — it is what it says.

The Syriac Scriptures and the Gospel of Barnabas

The book is believed to contain a version of the Gospel of Barnabas, a text long referenced in historical writings but rarely seen in such ancient form. In it, the crucifixion story unfolds very differently from the one recorded in the canonical Gospels of the New Testament.

According to this text, Jesus was never crucified. Instead, it claims that Judas Iscariot, the disciple who betrayed him, was transformed to resemble Jesus — and it was Judas, not Christ, who was executed on the cross. The gospel further asserts that Jesus ascended to Heaven alive, escaping the earthly suffering described in Christian tradition.

Such a version aligns more closely with certain Islamic teachings found in the Qur’an, which also deny the crucifixion and suggest that Jesus was taken up by God. This overlap has led some scholars to suggest that the manuscript may represent a bridge between early Christian and later Islamic thought.

Vatican Interest and Scholarly Debate

News of the manuscript’s existence quickly drew attention from religious institutions around the world. Reports suggest that the Vatican formally requested permission to study the text to assess its contents and authenticity.

Meanwhile, experts continue to debate whether the book is an early copy of a known apocryphal text or a later reinterpretation written in ancient style. While radiocarbon analysis confirms its age, scholars remain cautious, noting that ancient texts often reflect complex theological movements rather than factual accounts.

Still, the potential implications are profound: if authenticated as a genuine 6th-century version of the Gospel of Barnabas, the manuscript could force historians to revisit long-held assumptions about the diversity of early Christian belief.

A Call for Open-Minded Examination

For believers and skeptics alike, the ancient Bible serves as a reminder that history is rarely as clear-cut as tradition suggests. Each new discovery — whether confirming or challenging established doctrine — adds nuance to humanity’s ongoing search for truth.

While some view the text as heretical, others see it as a historical treasure, a piece of the vast mosaic that shaped early faith and philosophy. Its existence underscores how many voices and versions once vied to define the story of Jesus — and how some were lost, suppressed, or forgotten.

As scholars continue their work, one truth remains certain: the past still has secrets to tell. And sometimes, they emerge not to erase belief, but to deepen our understanding of how profoundly human the search for divine truth has always been.

Sources

- BBC News – Ancient Bible Found in Turkey Sparks Debate

- The Guardian – The Gospel of Barnabas and Early Christian Texts

- National Geographic – Lost Gospels and the History of Christianity

- Smithsonian Magazine – The Syriac Manuscripts and Early Biblical Variants

- Reuters – Vatican Scholars Request Access to Ancient Biblical Manuscript