The summer of 1843 weighed heavy over Mobile, Alabama. Heat clung to the docks like a second skin, bringing with it the smells of brine, sweat, and sour rum. Buyers gathered near the auction platform, fanning themselves and trading rumors about a particularly unusual “shipment” that had arrived from the Caribbean.

When the hold door of the merchant ship Deliverance was forced open, the noise dipped to a low murmur. Shackled men shuffled into view—thin, exhausted, eyes dull from the crossing.

Then the last man stepped through.

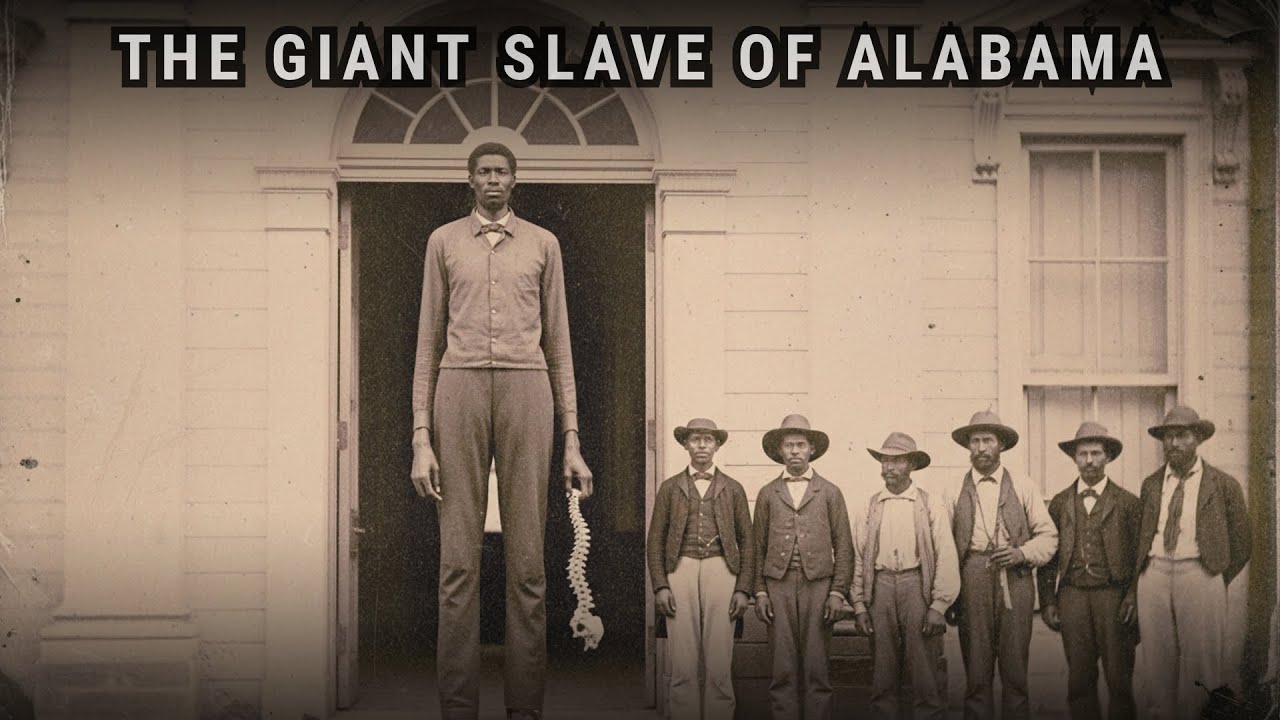

He had to duck under the frame. Even hunched, his shoulders scraped the door. When he straightened as much as the chains allowed, the crowd seemed to lean back all at once.

No one knew his exact height, but estimates flew—six and a half feet, six foot ten, maybe even more. His bare feet were planted wide for balance, his wrists locked in heavy iron cuffs usually reserved for cargo. He looked underfed, yet his chest, shoulders, and arms still carried an intimidating solidity. His skin was deep and dark, his back marked by old scars that hinted at a long history of punishment and survival.

He spoke a name in Haitian Creole, but it was quickly dismissed. The men on the docks gave him a new one instead, a name that would travel across plantations and into legend:

Samson.

Auctioneer Marcus Thornhill had worked the block for years. He had seen families torn apart, children sold with casual cruelty, and men broken by fear before they ever reached the fields. But the sight of Samson unsettled even him. The giant did not look at the buyers. His gaze fell somewhere beyond them, as if fixed on a memory he refused to release.

Rumors had arrived ahead of him—whispers of a plantation uprising in Haiti, of soldiers unable to subdue a man who seemed too strong to bend. In truth, no one knew what had happened. But fear did not need evidence. It needed only a story.

Bidding started high. It climbed faster.

Five hundred.

Six hundred.

Seven.

Eight.

Nine.

Finally, a voice in the back cut through the heated air.

“Twelve hundred dollars. Cash.”

Heads turned. The speaker leaned on a carved cane, dressed in the understated confidence of an old planter: Thomas Whitmore, owner of a vast cotton plantation along the Tombigbee River.

No one topped his offer.

The gavel fell.

Samson had a new owner—and a new chapter in a story that would grow far beyond the man himself.

Whitmore Plantation and the Overseer Who Ruled by Fear

The wagon ride north carried Samson through forests of pine and stretches of red clay roads. Whitmore Plantation rose out of the landscape like a self-contained world: endless cotton fields, rows of cramped cabins, and a white house perched on a hill, watching everything.

Waiting near the main yard was the man who kept daily order: James Rutledge, the overseer.

He was not tall, but everything about him signaled control—a stiff posture, a firm grip on his whip, the measured stomp of his boots. In a system built on fear, Rutledge was the instrument that made fear tangible.

Whitmore made a brief introduction, then retreated into the shade of his house.

Rutledge walked up until he stood directly in front of Samson.

“Look at me when I speak,” he said.

Samson met his eyes.

The overseer hesitated for a fraction of a second, taken aback by the clarity and steadiness he saw there. This was not the gaze of someone already defeated.

“You’ll call me ‘sir,’” Rutledge continued. “You’ll work where I say and how I say. You’ll meet your quota or answer to me.”

Samson remained silent.

“I asked if you understand,” Rutledge pressed.

“Yes, sir,” Samson replied at last. The words were empty of emotion—neither submissive nor defiant. They sounded more like a note recorded in his mind.

Rutledge, who was used to fear or pleading, did not know what to do with that kind of answer. It bothered him more than he admitted.

The First Punishment and the Lesson Underneath

On his first day in the fields, Samson was assigned a quota harsher than most: three hundred pounds of cotton, when two hundred already stretched the human body to its limits.

By midday, he was far behind. His hands were rough but inexperienced. His shoulders still ached from weeks of confinement on the ship. When Rutledge inspected his sack and found barely sixty pounds, he saw an opportunity to assert control in front of everyone.

He ordered Samson to remove his shirt. The people working nearby glanced away, knowing what was coming.

The whip cut into his back again and again. Samson reacted like any human being would—flinching, tensing, sucking in his breath. The overseer pushed on, partly to maintain authority, partly to prove to himself that the giant was just a man.

“Say you’ll do better,” Rutledge demanded.

Samson’s voice came out rough. “I’ll meet whatever work you give me, sir.”

The phrasing was careful. It sounded obedient, but something in the tone made listeners realize Samson was not surrendering, merely acknowledging the situation.

That night in Cabin Seven, an older healer named Esther tended his wounds with a quiet, practiced gentleness. A younger man, Isaiah, watched Samson cautiously.

“You should’ve answered him sooner,” Isaiah whispered. “It might’ve spared you the whip.”

Samson’s reply was simple, but it revealed the difference between how he saw the world and how the overseer did.

“I needed to see how he acts when he thinks no one can stop him,” Samson said. “How long he will go. How he breathes. Which side he favors when he swings. If I must live under him, I must understand him.”

Esther studied him thoughtfully.

“You’re not just trying to survive, are you?” she asked.

Samson didn’t answer directly.

“I don’t plan to die on another man’s schedule,” he said. “That’s all.”

Counting Cotton and Watching Patterns

Days became weeks. Samson learned the grim mathematics of the fields.

Each pound of cotton took dozens of bolls.

Each sack filled meant hundreds of repetitions.

Each day’s quota demanded tens of thousands of small, painful actions.

Most people counted only by exhaustion. Samson counted by numbers.

He tracked how long it took to fill one row, how much weight he could realistically carry in a day, how much extra effort would attract punishment rather than protection. He noticed who helped whom in the field, who collapsed from pace, who quietly shared their rations.

He also watched Rutledge.

When the overseer made his rounds, Samson saw the pattern in his movements—the way he favored his left leg, the rhythm with which he scanned the rows, the moments he was most alert and the times his attention wandered.

Whitmore believed he owned the people in the cabins. Rutledge believed he controlled them.

Samson believed that understanding those beliefs was his only real leverage.

When Numbers Turned Against the Overseer

One afternoon, after Samson had finally reached the three-hundred-pound quota assigned to him, Rutledge checked his ledger and announced loudly that the target had been four hundred.

Workers nearby stiffened. They had watched Samson labor methodically all day, pushing himself well past reasonable limits.

Samson looked at the altered numbers, still glistening slightly with fresh ink.

He did not argue.

“My mistake, sir,” he said quietly.

It was a calculated answer, the kind that gave Rutledge just enough room to step back without losing face. But the overseer didn’t. He demanded another public punishment anyway.

Later, as Esther wrapped fresh bandages over old scars, Samson murmured to Isaiah, “He just showed everyone he’ll change the numbers whenever it suits him. Sooner or later, he’ll do it when the wrong person is watching.”

Isaiah frowned. “You’re waiting for him to slip?”

Samson nodded once. “He believes fear is his strongest weapon. But fear makes a man careless when he thinks no one can challenge him.”

The turning point came days later.

Rutledge again set Samson’s quota at an impossible mark, despite his still-healing injuries. The others saw it clearly this time. Quietly, without speeches or plans, they began to help—handing Samson cotton, stepping into his row when the overseer’s back was turned, redistributing their own sacks.

By sunset, Samson’s tally was close enough to the demand that Rutledge had to inspect more carefully. He rode over, whip in hand, ready to accuse someone of cheating.

Before he could, Samson spoke in a calm, even tone.

“If you keep raising numbers you can’t justify, Whitmore will see that the cotton weighed doesn’t match what’s written in your book,” he said. “He checks it every week. You know he does.”

The sentence landed with more force than any blow.

Rutledge relied on Whitmore’s trust. Any sign that he was falsifying records could cost him his position—and his sense of power.

The workers watched, silent. An overseer used to absolute command now faced a simple truth: someone else understood the system as well as he did.

A Legend Built on Fear

Over the following years, stories about Samson spread far beyond Whitmore Plantation. In some versions, he snapped overseers’ spines with his bare hands. In others, he led uprisings and vanished into the swamps, leaving terror in his wake.

The reality, as often happens, was far quieter and more complex.

Samson did not become a one-man army. He did not single-handedly overturn the system that tried to contain him. But he did reshape life in the narrow space he could affect.

He helped others manage their quotas, teaching them how to count and pace themselves to avoid unnecessary punishment. He warned people when Rutledge was in a dangerous mood. He stepped in quietly when someone was on the verge of collapse, taking just enough of their load to bring them through the day.

The myth of a “cursed” giant who destroyed overseers likely grew from a simpler truth: men like Rutledge began to fear him—not because he was violent, but because he could not be intimidated in the ways they expected. And fear breeds exaggeration.

Over time, the overseer who once walked the fields with absolute confidence developed a restlessness people could see. He drank more. He slept less. He paced the yard at night, glancing toward Cabin Seven as though expecting something to happen.

Eventually, Rutledge left Whitmore Plantation—not in a dramatic confrontation, but under the weight of his own anxiety and declining health. A new overseer took his place, one who relied less on arbitrary cruelty and more on efficiency, if only to maintain order.

Samson remained.

The Man Behind the Myth

Samson lived long enough to see the country bend toward war and transformation. He watched children born into bondage grow into adults who would someday hear the word “freedom” applied to them for the first time.

He died quietly, buried behind the cabins without a marked grave or carved stone, like so many who endured the same system.

What survived was not just the myth of his size or the whispered tales of what he might have done, but something more enduring: the knowledge that even within the harshest constraints, a person could still think, still calculate, still influence the balance of fear.

In the end, Samson’s “curse” was not a supernatural force or a trail of broken men.

It was the simple, dangerous fact that he refused to see himself only as an object in someone else’s ledger—and showed others, by example, how to read the system that tried to control them.