Some stories lie buried in archives for so long that people begin to believe they were never real at all. The Thornwood case in Bourbon County, Kentucky, was one of those stories – a half-remembered rumor about a plantation family that seemed to fall apart almost overnight in 1859. For generations, the name “Ezra” was mentioned in low voices, if at all.

In 2024, that changed.

Archivists at the Kentucky Historical Society opened a sealed trunk once belonging to Colonel Marcus Thornwood, a respected veteran of the Mexican War and owner of Thornwood Plantation. Inside were letters, ledgers, witness statements, and fragments of a journal. Together, they revealed the inner life of a household that appeared stable from the outside, but was slowly cracking from within. At the center of that story was a young enslaved man named Ezra, purchased in the spring of 1859, whose presence exposed the fault lines that had been hidden in the Thornwood family for years.

Thornwood Plantation had been built on tobacco, land, and strict discipline. Established in 1812, it spanned thousands of acres and was often compared to English country estates. Visitors saw polished floors, formal dinners, and carefully maintained grounds. What they could not see was the emotional distance inside the main house: a marriage long exhausted, daughters who felt trapped by expectations, and a patriarch who equated silence with strength.

Colonel Marcus Thornwood, in his mid-fifties by 1859, carried himself as a man in complete control. He had served in war, managed his land, and believed deeply in order. In his private letters, however, he admitted to feeling a persistent hollowness, “a coldness around the heart” that he could not ease. His wife, Victoria, felt it too. Married young, she had spent years fulfilling the role of the perfect plantation mistress. Behind the practiced smile, she wrote to her sister of feeling unseen and unheard, “a ghost wandering through my own life.”

Their four daughters each lived under the same roof but carried their own silent burdens. Amelia, the eldest at twenty-four, did everything expected of her but feared a future that looked exactly like her mother’s. Beatrice, at twenty-one, had a sharp intellect but little opportunity to use it. Clara, nineteen, was often unwell and easily overlooked. Dorothy, eighteen, bristled openly at the rules placed upon her, longing for a different kind of life. By the time Ezra arrived, the family was already fragile, even if no one wanted to admit it.

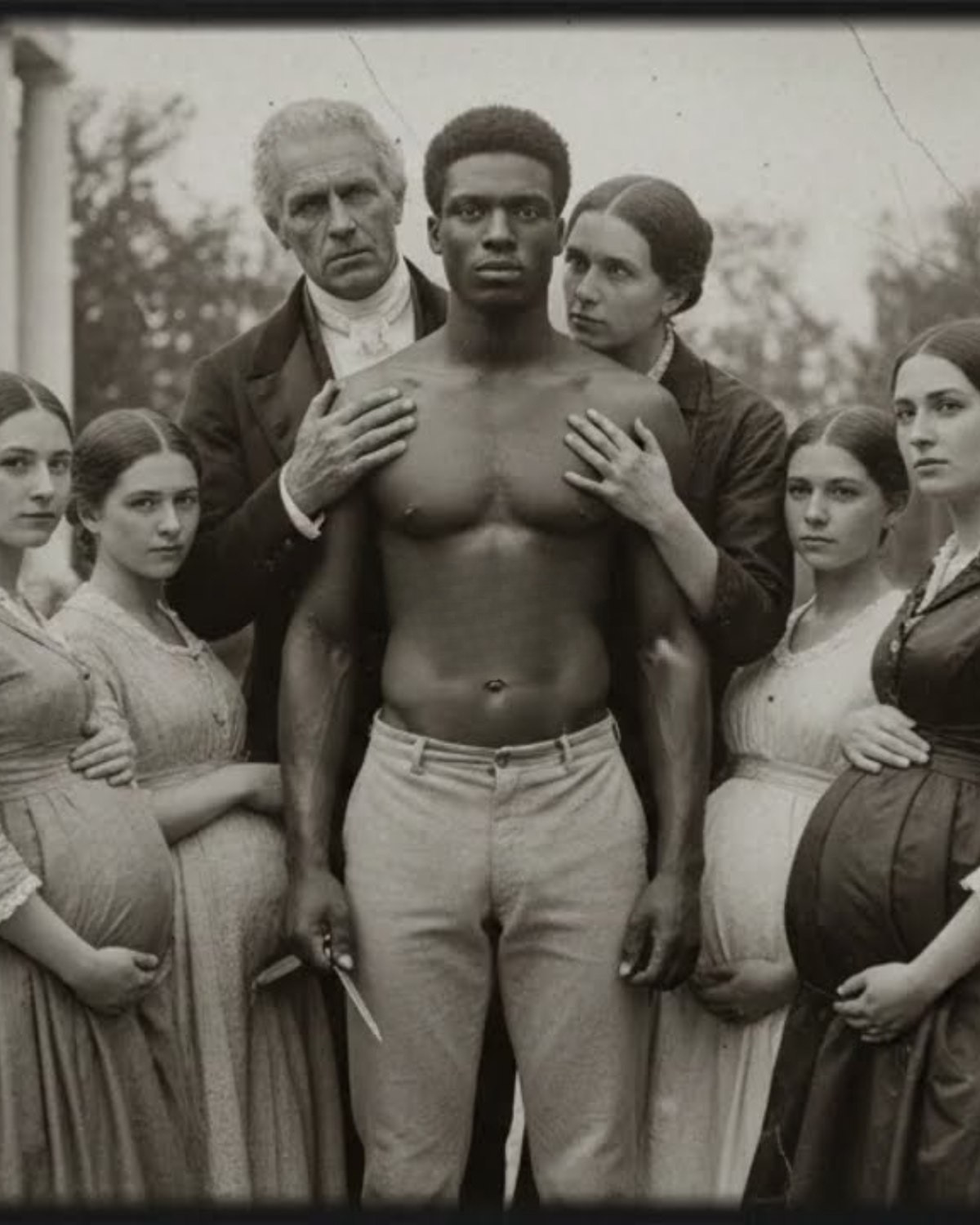

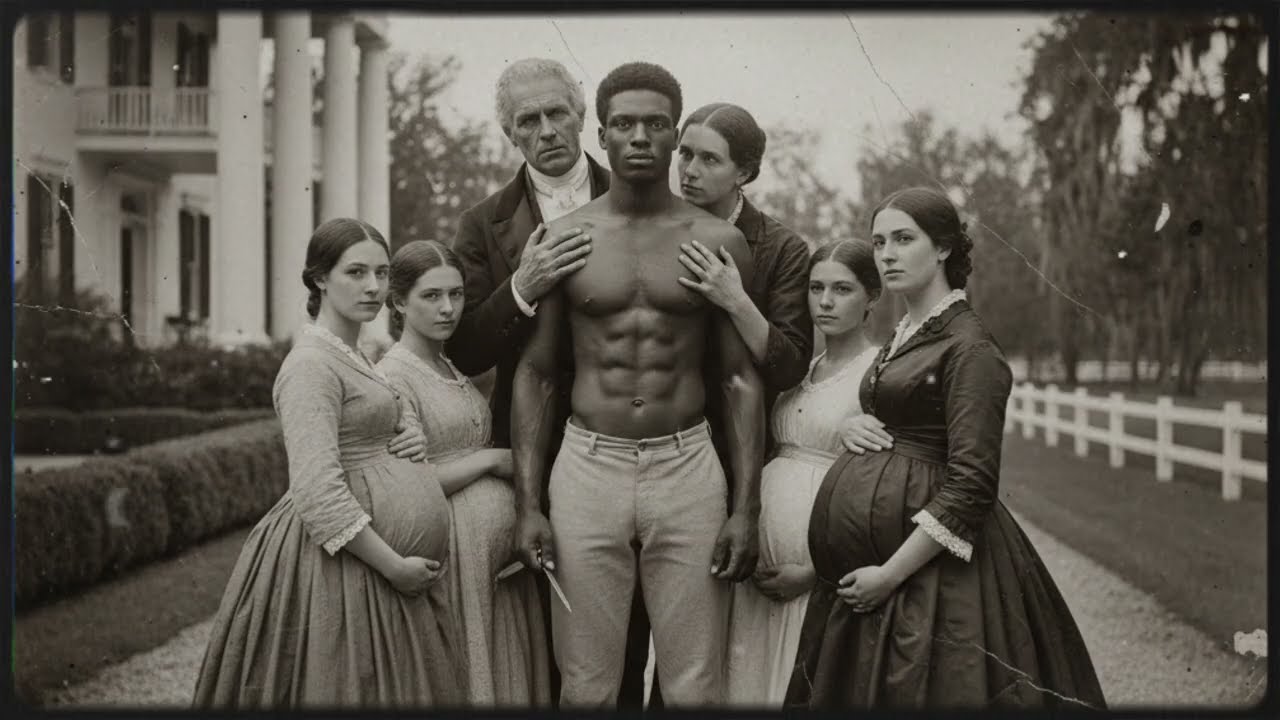

The records show that Marcus had not gone to Louisville in April 1859 intending to make any major changes to his household. He was there to observe crop prices and meet contacts. At the slave market, however, he noticed a young man who stood out immediately. Ezra, around nineteen or twenty, was described in the auction ledger as literate, perceptive, and suited to household work. Witnesses later said there was something about his calm posture and attentive gaze that made people pause.

The seller pulled Marcus aside and suggested that Ezra would be “more valuable in the house than in the fields.” Whatever reservations Marcus had, he set them aside and paid a notably high sum for Ezra. By the next morning, Ezra was at Thornwood.

The documents recovered from the trunk do not detail specific events in explicit terms, but they draw a clear picture of how quickly the dynamic between Marcus and Ezra became complicated. Within weeks, the colonel’s letters show a man wrestling with deep discomfort, guilt, and emotional dependence. He had spent his life insisting on self-control and authority; now he found himself confiding in someone he legally owned – someone who, in turn, seemed to understand his vulnerabilities better than anyone in his own family.

Other testimonies, including those of formerly enslaved people interviewed years later, describe Ezra as exceptionally observant. He learned the rhythms of the house, the fears of its owner, and the unspoken tensions in the family. He did not raise his voice or confront anyone directly. Instead, he listened, noticed, and responded with a kind of steady presence that unsettled those who were used to being the ones in charge.

It was Victoria who next became aware of how much had shifted. Accustomed to her husband’s emotional distance, she began to notice his distracted behavior and unexplained absences. One morning, following him at a distance, she saw a moment that overturned everything she thought she knew about her marriage and her husband’s unshakable authority. What affected her most was not scandal, but the realization that the rigid hierarchy she had lived under was not as simple as she had believed.

In the weeks that followed, Victoria’s own interactions with Ezra became more substantial. She approached him not as a woman seeking to break rules for their own sake, but as someone deeply starved for conversation, warmth, and acknowledgement. The records do not dwell on the details, but her surviving notes reflect a sense of being noticed, of feeling alive after years of emotional numbness. For the first time, someone listened to her without judgment, without reminding her of duty.

One by one, the daughters were drawn into the same orbit. Amelia, who had spent her life doing what was expected, noticed the subtle changes in her parents and the tension in the air. When she discovered her mother’s connection to Ezra, she was shocked – then curious. In her private diary, she wrote that he was “the only person in this house who looks at me as if I exist beyond my responsibilities.”

Beatrice, always observing, tried at first to treat Ezra as a subject of study. She asked questions, tested his insights, and found herself increasingly unsettled by how accurately he read the family’s patterns. Clara, frequently overlooked, found in him someone who recognized her presence without dismissing her as frail or fragile. Dorothy, restless and rebellious, saw in the changing household dynamic a chance to push against the structure that had confined her since childhood.

Was Ezra intentionally drawing them in, or simply responding to needs that had been neglected for years? The archive does not offer a simple answer. Some writings suggest a deliberate strategy: a man who had suffered under previous owners learning to navigate the only space of influence available to him. Other fragments show someone who understood that when people feel continually unseen, they will cling to the first person who truly pays attention.

What is clear is that, by late 1859, the Thornwood family no longer revolved around Marcus’s authority. Every member of the household, in different ways, had begun to orient themselves around Ezra – their confidences, their frustrations, their longings. The formal structure remained, but emotionally, the center of gravity had shifted.

The breaking point came within months. Financial records show that the plantation’s management began to suffer. Marcus neglected correspondence, delayed decisions, and failed to address conflicts among staff. There are hints of disputes between overseers and the family, disagreements over discipline, and growing unrest among the enslaved people who observed the household’s changes.

Then came the fire.

On a night in early 1860, a blaze broke out in the root cellar beneath the main house. The exact cause was never conclusively determined. Some witnesses spoke of an accident with stored supplies; others suspected deliberate action, though no formal charge was ever proved. What is known is that the fire spread quickly and exposed how unprepared the plantation was for crisis.

Marcus inhaled smoke while helping to fight the flames and died a few days later. Victoria survived physically but struggled mentally from that point onward, described in letters as “never fully returning to herself.” One daughter left Kentucky entirely and disappeared from local records. Another was later placed in a care institution. The younger two appear in scattered documents from Northern states in the years leading up to the Civil War, suggesting they left with outside help.

As for Ezra, the records become thin and contradictory. Some reports claim he was confined shortly before the fire, as Marcus attempted to reassert control. Others suggest he was last seen near the outbuildings on the night of the blaze. No burial record under his name has been found. Whether he died there or escaped remains unknown.

What the trunk does make clear is that the Thornwood story was not simply about one man exerting influence over those who owned him. It was about a family already under immense internal pressure meeting someone who refused to play the roles they expected. In a system built on control, silence, and hierarchy, the presence of a person who listened, questioned, and quietly observed acted like a catalyst. Old secrets rose to the surface. The gap between how the family appeared and how they felt became too wide to maintain.

Some later commentators have framed Ezra as a master manipulator. Others see him as a survivor using the only tools available in an unjust world. Still others argue that the Thornwoods were the primary authors of their own downfall, having built a life on emotional repression and rigid roles that could not withstand honest reflection.

Perhaps the most balanced conclusion is that this was a meeting of vulnerabilities: a man who had been deeply harmed learning to read the weaknesses of those around him, and a family whose carefully maintained order was not as stable as it looked. When those forces collided, the old structure could not hold.

One surviving line from Clara’s correspondence, written years later under a different name, captures the lasting impression of that year at Thornwood:

“We thought he was the one being controlled. We were wrong. We had built a house on silence, and he was the first to show us how loud that silence really was.”

Over a century and a half later, the Thornwood documents do not just tell the story of one plantation. They invite a deeper look at how power, dependency, and unspoken needs can reshape any household, especially one already standing on unstable ground.