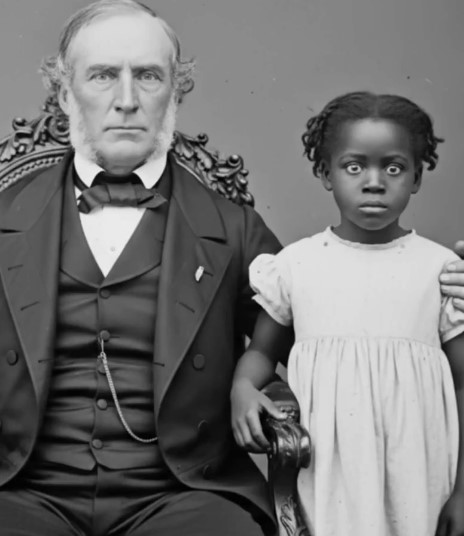

For over one hundred years, a faded photograph from 1858 rested quietly in a university archive — catalogued, boxed, and largely overlooked. Countless students, researchers, and archivists passed the worn paper image believing it was nothing more than a typical family portrait from the mid-19th century.

The photograph showed a young woman seated in a plain chair and a small boy standing beside her. Their clothing was simple, their expressions subdued, and their posture formal in the way early photographic subjects usually appeared. Nothing about the image seemed unusual. It resembled the thousands of early portraits taken throughout the American South before the Civil War.

For decades, that assumption went unquestioned. But a routine digital preservation project in 2023 revealed that the photograph contained something far more complicated — and far more painful — than anyone had realized.

The Restoration Project That Changed Its Meaning

In an effort to digitize thousands of 19th-century photographs stored in climate-controlled rooms across Charleston, a team of historians and archivists began scanning each image at high resolution. The goal was simple: preserve history.

One photograph, however, did not behave like the others.

When enhanced using modern imaging software, faint shadows behind the woman and child sharpened into legible shapes. Smudges became strokes of ink. What had once been indistinguishable texture revealed itself as writing.

Lines of writing that had been invisible for more than a century emerged with startling clarity.

Behind the woman’s shoulder, in looping 19th-century script, archivists read the words:

“Lot 436 – Female, age 24, with child (male), age 3.”

The image was not a family portrait.

It was an auction listing.

Everything researchers thought they knew about the photograph had to be re-examined.

When Photography Became a Tool of Recordkeeping

Historians quickly traced the handwriting back to known auction clerks associated with the Charleston Exchange, one of the busiest slave markets in the antebellum South. The writing style, the ink pattern, and the numbering system matched ledger books still preserved in the same region.

The photograph’s purpose suddenly shifted from sentimental portrait to documentation — an early example of how photography was used in the 1850s not to preserve family memory, but to support the administrative systems of slavery.

In the mid-19th century, some enslavers commissioned photographs to:

• inventory enslaved people

• provide evidence of ownership

• demonstrate condition for potential buyers

• document family units being sold together

These images were often stored with business papers, not personal albums.

The woman and child in the photograph were not being commemorated; they were being recorded.

Subtle Details Revealed by Technology

The digital enhancement also illuminated other small but telling features in the photograph — elements unnoticed for more than a century.

The woman’s hand, resting lightly on the small boy’s shoulder, initially appeared to be a gesture of affection. But experts recognized it as a standard pose used in inspection photographs meant to show height and posture.

A faint rectangle of cloth beneath their feet indicated they had been asked to stand on a clean, neutral background — a common practice in early documentation photography.

These details transformed the photograph from a seemingly gentle testimonial into evidence of a transactional system that treated human lives as items to be cataloged.

A Painful Connection to the Past

Once the writing was deciphered, researchers cross-referenced the numbers with surviving 1858 auction records. While the names of the woman and child were not included in the original listing, the ages and descriptions aligned with entries connected to one of the largest slave auctions in American history — the 1859 sale often referred to as the “Weeping Time,” where more than 400 individuals were sold over two days.

Although the photograph itself predates that event by one year, the documentation style mirrors the methods used by the same network of traders and brokers, suggesting the image may have been taken during a period of intensified record-keeping.

The Significance of Rediscovery

The museum staff who worked on the restoration described a profound shift in the room the moment the writing appeared. For generations, the woman and child had been presented to the public — when the photograph was occasionally displayed — as early examples of American portraiture.

Now, their image represented something entirely different.

Dr. Camille Rhodes, the archivist involved in the enhancement, explained the emotional impact of the discovery:

“It wasn’t simply a mislabeled photograph. It was an example of how ordinary objects can carry hidden truths. We were looking at a document of a system that sought to classify people as property.”

The museum chose not to hide the photograph after learning its true origin. Instead, they updated its display with historical context, teaching materials, and a description of the restoration process.

The decision transformed the image from an anonymous relic into an educational artifact.

An Example of How History Lives in Details

The rediscovery has sparked conversations nationwide about the role of photography in the era before the Civil War. While many Americans associate slavery primarily with plantations and labor, the photograph highlights the administrative systems — ledgers, receipts, numbered lists, and visual documentation — that supported the institution.

These records were not created with the intention of helping future generations understand the past. They were meant to facilitate commerce. And yet, ironically, they now serve as evidence that human dignity was disrupted, not erased.

Giving Visibility to Lives Lost in the Records

The identities of the woman and child are still unknown. Without their names, traditional genealogical research is difficult. Auction records from the 1850s often listed ages, descriptions, and prices, but omitted personal details.

Still, their image now stands for something larger.

It represents:

• those whose stories were never written

• those recorded as numbers instead of names

• those whose lives were preserved only accidentally

• those who lived through a system that documented ownership but not identity

Their silent photograph — one that once seemed ordinary — now carries the weight of remembrance for countless families who were never afforded a written history.

A New Chapter for an Old Image

Today, the restored photograph is displayed with the enhanced text visible. Visitors often linger longer than expected, captivated not by the photograph’s age, but by what it symbolizes.

What was once a quiet archival object has become a teaching tool that forces viewers to reconsider the role of photography in history. It reminds us that the past is embedded in objects we assume we already understand — that hidden stories can remain concealed until technology, curiosity, and circumstance bring them into view.

“This photograph challenges us to recognize that slavery was not only about labor,” said Dr. Rhodes. “It was also a structured system of documentation, classification, and control. And sometimes, those systems left behind traces that speak to us generations later.”

A Reminder That History Waits to Be Seen Clearly

The restored 1858 image has become a symbol of the importance of re-examining historical materials. It illustrates how a single photograph, once dismissed as harmless or generic, can illuminate the realities of a system that shaped millions of lives.

The woman and child in the portrait may never be identified by name, but their image allows the public to confront history with clarity, empathy, and renewed understanding.

Their presence — frozen for more than a century in fading ink and early photographic grain — now stands as a reminder that behind every number, every notation, and every “lot,” there was a life, a family, and a story that deserved to be remembered.