In rural Alabama, stories have a way of surviving even when people try to bury them. They survive in courthouse ledgers that no one opens, in family Bibles with pages glued shut, in land deeds folded and refolded until the ink fades. And sometimes they survive in whispers—passed down like a warning from one generation to the next.

One of those whispers, repeated for more than a century, circles around a pair of twin sisters said to have lived on a plantation outside Camden in the early 1840s. Their names appear in fragments of records—Margaret and Martha Ellison—daughters of a strict and influential landowner who ran his estate with the hard certainty of a man who believed authority was the same thing as righteousness.

To outsiders, the Ellison house was a postcard of prosperity: white columns, carefully trimmed grounds, cotton fields stretching like an ocean. The kind of place that looked peaceful from the road. But people who lived nearby had a different expression for such homes.

The prettier the porch, the darker the hallway.

Margaret and Martha were born in 1819, minutes apart, and raised in an environment built on silence. Their mother died shortly after their birth, and the household that remained was run more like a command post than a family home. The twins were educated privately, dressed well, and taught to embody refinement—but also taught, in ways spoken and unspoken, that they belonged to their father’s plans.

In communities like theirs, reputation was currency. It bought forgiveness, deflected questions, and kept doors closed. And the Ellison name—respected in public—was protected at all costs.

As the twins grew, townspeople said they were indistinguishable at first glance. But those closest to the household described something subtler: Margaret was controlled, observant, careful with her words. Martha was restless, impulsive, and more willing to test boundaries. Their closeness was intense in the way childhood grief can bind people together—two halves forming a single unit, especially in a home where tenderness was scarce.

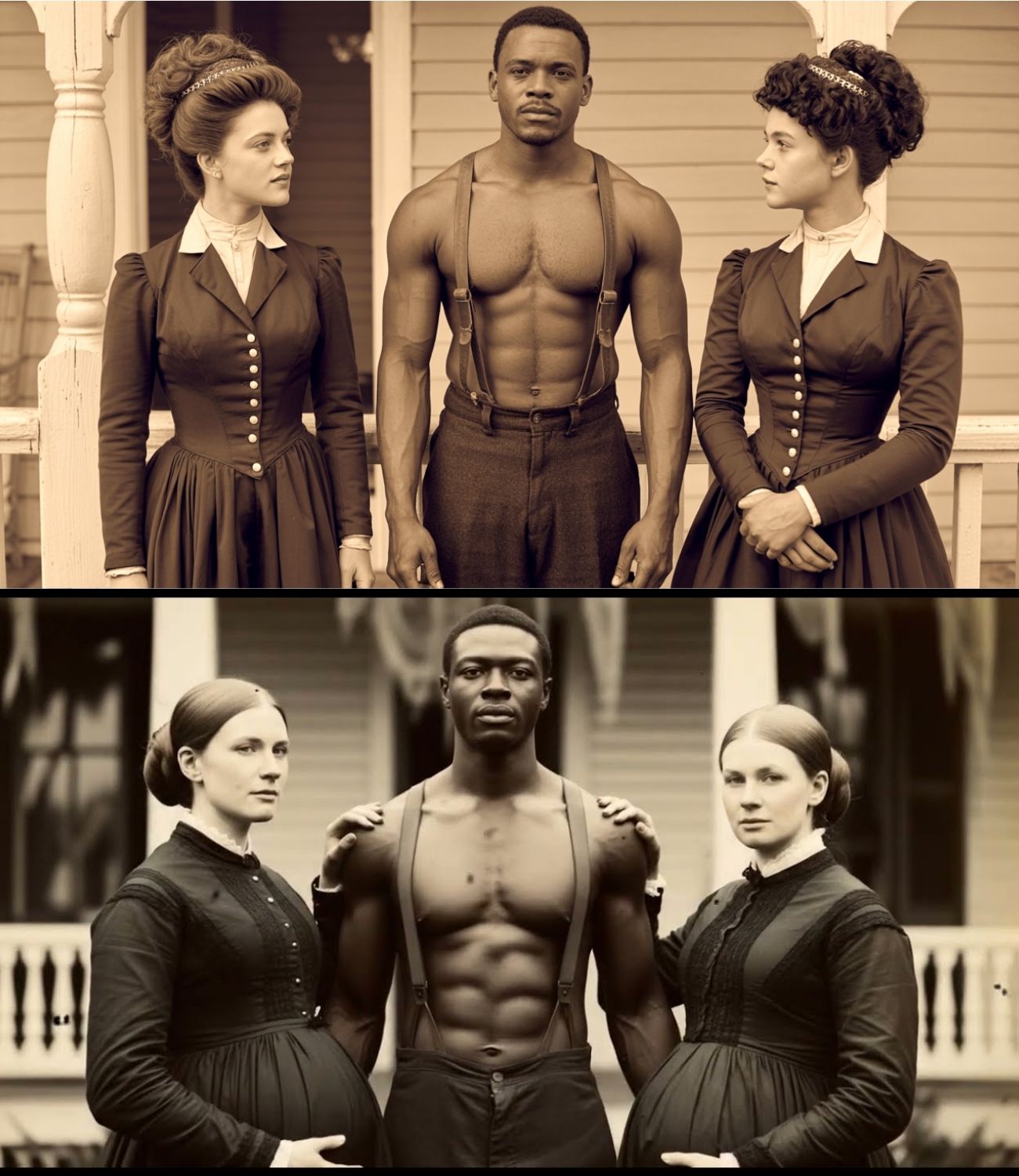

Then, in the late 1830s, a new name appears in scattered plantation records: Isaac. The official documents identify him only by a first name and job assignment—stable work, repairs, horse handling. Like countless others, he was reduced to a line item. Yet oral histories collected decades later describe him differently: quiet, capable, and unusually educated for someone trapped in a system designed to limit knowledge and movement.

That detail matters, because it changes the texture of what came next.

According to personal letters attributed to a neighboring family, the twins began spending time near the stables more often than expected. No record states what was said or why those visits began, and responsible historians avoid pretending certainty where there is none. But the pattern—two sheltered young women drawn toward the one place on the property associated with freedom of movement—created speculation then, and it fuels speculation now.

In the early 1840s, Colonel Benjamin Ellison reportedly attempted to arrange marriages for both daughters, consistent with the customs of the era. Yet those negotiations collapsed more than once. The reasons are unclear. Some accounts cite “illness,” others hint at “unusual family tensions.” Whatever the truth, the twins did not marry, and that alone made them subjects of conversation.

Then the household changed.

Neighbors wrote of lights burning late into the night. Of the sisters withdrawing from church events. Of servants leaving. Of the estate becoming quieter—less like a home and more like a sealed container. People filled the silence with whatever explanation best matched their fears: a curse, madness, shame, divine punishment. But superstition often functions as a mask for something more real: a community sensing harm yet unwilling to name it.

The clearest thread in the surviving material is not romance, but control. In a society built on hierarchy, relationships across lines of power could never be equal, never fully chosen, never free of coercion. When modern audiences hear stories from this era, the temptation is to reduce them to scandal. That impulse misses the point. The true story—wherever the facts land—would be about a system that distorted everyone inside it.

It is in that context that later testimony becomes especially important.

Decades after the Civil War, a formerly enslaved woman named Rachel Douglas was interviewed as part of a local history project. Her words—preserved in summary form—do not read like gossip. They read like exhaustion. She described the Ellison home as a place where the air felt heavy, where fear moved from room to room, and where the twins, despite their privilege, seemed trapped inside something they could not control.

She also described Isaac as a person who carried himself with quiet restraint, and she spoke of punishments on the property as routine—an everyday mechanism of power, administered not as justice but as enforcement. In her recollection, the household’s tensions were not merely personal—they were structural, produced by an environment that trained people to treat others as possessions.

Within a year, whispers shifted into something more specific: hidden births.

This is where the historical record becomes foggier and where responsible writing must slow down. In some versions of the story, two infants were born in secrecy. In others, there was only one child, moved away quickly. Some accounts describe altered ledgers or missing entries. A later-discovered family clause—reportedly inserted into a will—suggested that any children connected to the daughters would be denied inheritance and the family name.

That kind of clause, if authentic, would not prove paternity. But it would suggest panic: a family anticipating the need to erase.

After Colonel Ellison’s death in the early 1840s, the twins withdrew further. Travelers’ journals from the period—often unreliable in detail but revealing in tone—described the estate as oddly still, as if the house itself was holding its breath. A boy was reportedly seen near the stables, watched closely, never introduced. Again, this proves nothing. But it shows how consistently observers noticed the same theme: concealment.

The story’s most dramatic turning point—recorded in local tradition more than in official documents—was a fire. The east side of the home burned, and although the sisters survived, Isaac did not appear again in any later plantation lists. No confirmed remains were documented. No public notice was filed. In an era when an enslaved person could “disappear” without legal consequence, the absence of a record is not evidence of a single outcome. It is simply evidence of power.

For decades, the Ellison property declined. Eventually it was abandoned, reclaimed by the landscape. In the early 20th century, surveyors cataloging forgotten estates reportedly found damaged personal items—letters, partial diaries, and household fragments. Some accounts claim there was a small notebook bearing Isaac’s name; others suggest that attribution was added later by archivists eager for a clean narrative.

What is more credible is the broader pattern that scholars frequently document across the South: families attempting to seal records, rewrite genealogies, and remove inconvenient names from public memory. The Ellison story fits that pattern, whether every dramatic detail is literal or not.

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, renewed interest in genealogy and historical trauma brought new attention to cases like this. Researchers began to compare church records, probate files, and cemetery maps. Some families—Black and white—found themselves connected by lines that had been intentionally obscured.

That’s the unsettling truth at the heart of the legend: not the rumor of “forbidden love,” but the reality that slavery entangled bloodlines, identities, and histories in ways people later tried to deny. A system that treated human beings as property did not simply exploit bodies—it distorted families, law, religion, and memory itself.

And so the so-called “mirror house” becomes more than a ghost story. It becomes a metaphor.

A mirror reflects what stands before it. But a cracked mirror reflects in fragments—overlapping faces, incomplete shapes, distorted outlines. That is what these archives often offer us: not clean answers, but evidence of what people tried to hide. Not a neat morality play, but a record of human beings caught in a machine built to remove choice.

If the Ellison twins were real people behind the myth—and they were—then their lives were shaped by the constraints of their era and the brutal hierarchy their family benefited from. If Isaac was real—and records suggest he was—then his story would be the most important one, not because it’s mysterious, but because it represents countless lives reduced to footnotes.

And Rachel’s testimony, brief as it is, matters because it refuses the easy version of history. It doesn’t frame the Ellison home as “cursed.” It frames it as constructed—built from control, protected by silence, and destined to rot from the inside out.

In the end, whether every whispered detail is verifiable or not, the lesson remains painfully clear: when a society builds comfort on coercion, the cost does not vanish. It travels forward—through records, through families, through the stories people tell when official history refuses to speak.

The real question isn’t whether the legend is dramatic.

The question is why so many legends like it exist—why so many archives contain gaps where names should be, why so many family trees have branches sawed off, why so many communities learned to treat silence as virtue.

Because the darkest secrets don’t survive because they’re supernatural.

They survive because someone had the power to hide them.