In the aging, humidity-warped records of a plantation in northeastern Alabama, there is an entry so unusual that historians still struggle to classify it. Dated March 1856, it describes an incident at Harrington Plantation in which twelve white overseers, armed and authorized by law, failed to restrain a single enslaved man.

These overseers were not new to their roles. They were experienced, organized, and supported by the full force of the slave system. They carried weapons. They had numbers on their side. They assumed the outcome was guaranteed.

Yet they did not succeed.

What they witnessed that morning affected them so deeply that:

-

Three resigned within days

-

At least one was permanently injured

-

Two refused for the rest of their lives to talk about what had happened

Plantation owner Colonel Marcus Harrington ordered that all documents regarding the event be sealed. Families were paid to keep quiet. No newspaper reported on it.

Still, the story survived.

It did not survive because the owner preserved it. It survived because the enslaved people remembered it, repeated it, and passed it down.

What happened that morning was not a legend, nor a supernatural tale, nor an exaggeration created by fear. It was something much simpler—and far more threatening to the logic of slavery.

It was evidence that even the harshest system still depended on one fragile element: the willingness of human beings to comply.

To understand how one man disrupted the order of an entire plantation, we have to understand him: the man who walked away from Harrington Plantation and disappeared into the wider world.

This is the story of Jacob Terrell.

A Plantation Built on Numbers and Control

In 1856, Harrington Plantation was among the most profitable operations in Madison County, Alabama. Spanning some 3,000 acres of fertile bottomland near the Tallapoosa River, it was built on cotton and strict discipline.

The plantation’s structure included:

-

Around 240 enslaved laborers

-

17 white overseers

-

Roughly 1,500 bales of cotton produced per year

-

Fields, mills, cotton gins, worker cabins, and designated punishment areas

The main house, a large Greek Revival mansion, symbolized wealth and status. But the true power of Harrington Plantation lay in its systematic approach to control.

Colonel Marcus Harrington kept detailed records on every person he owned:

-

Daily work output

-

Hours in the fields

-

Punishments administered

-

Injuries recorded

-

Deaths noted in the ledgers

He saw himself not simply as a landowner, but as a manager of a complex system. Precision, routine, and predictability were his pride.

So when he purchased a man named Jacob Terrell in Richmond in 1852 for the unusually high price of $2,000—three times the typical price—Harrington believed he had made a particularly valuable investment.

A Quiet, Powerful Man

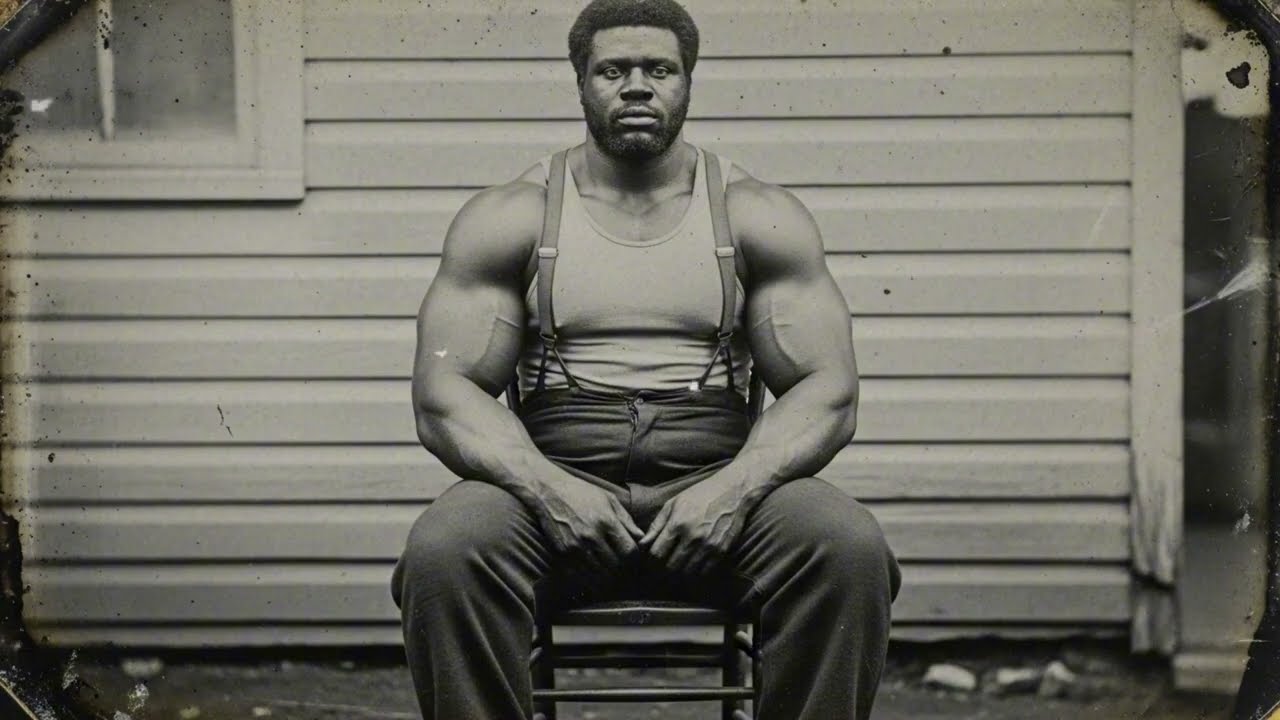

Descriptions preserved in archival notes portray Jacob as follows:

-

Age: around 28

-

Height: about 6 feet 7 inches

-

Weight: approximately 260 pounds

-

Background: raised on an iron plantation, used to industrial labor

-

Build: dense, powerful muscles developed by ironwork and timber

-

Temperament: quiet, steady, with no recorded history of rebellion

Jacob’s strength differed from that of most field workers. His body had been shaped by forges and furnaces rather than only cotton rows, giving him a compact, resilient kind of power.

On Harrington Plantation, he worked hard, spoke rarely, and did as he was ordered—for nearly four years. Overseers described him with words like:

“Reliable.”

“Mechanical.”

“Predictable.”

He was exactly the type of worker owners hoped for: efficient, calm, and seemingly resigned to his fate.

But during the winter of 1855, something changed.

The Letter That Changed Everything

At some point, a letter reached Jacob.

Enslaved people were generally forbidden from receiving mail, so how that letter found its way to him remains uncertain. Witnesses later recalled seeing him behind the cookhouse, standing completely still, staring at a single piece of paper in his hands.

His hands trembled.

His expression seemed empty, as though something inside him had collapsed.

No one on the white side of the plantation knew what the letter contained. Not the overseers, not the colonel. Even among the enslaved community, the details were not widely shared at the time.

But from that day forward, overseers began to notice small changes:

-

Jacob asked about property boundaries

-

He quietly inquired about river depth and crossing points

-

He wanted to know the distance to the next counties

-

He showed interest in routes that led away from the plantation

He was not organizing an uprising. He was not threatening anyone. He was planning something much more personal and final: an end to his own submission.

One elder later described the feeling around Jacob as “the stillness before a storm.” He did not become louder or more aggressive. He simply became inwardly unafraid.

When a man stops fearing punishment, he becomes very difficult to control.

March 14, 1856: The Confrontation

The morning began like many others. A low fog covered the fields, softening the outlines of buildings and trees. Work started at first light.

Around 7:15 a.m., three overseers approached Jacob near the cotton press. There was some kind of exchange—a disagreement, perhaps, or a demand. One of the overseers, angered, raised his strap and struck Jacob.

Jacob did not react.

Another overseer grabbed his arm, expecting resistance, flinching, or an attempt to pull away. Instead, he felt what he later compared to trying to move a solid wooden beam. Jacob did not struggle, did not fight back, but he refused to move as ordered.

Humiliated, one overseer fired his pistol into the air to summon help.

Four more overseers arrived. Then five more. Soon there were twelve men surrounding one unarmed man.

What happened next appears consistently in the surviving testimonies.

The twelve men attempted to seize Jacob at once. What followed was confusion and chaos: men stumbling, colliding with each other, being pulled off balance by their own force and momentum. A shoulder was dislocated. Ribs were broken. At least one overseer lost consciousness.

Jacob, however, was not described as striking anyone. He did not attack them. He simply refused to be moved, bracing himself against their attempts, stepping or twisting just enough to let their own weight work against them.

To those watching, it did not look like a brawl. It looked like twelve men trying—and failing—to shift something that no longer agreed to bend.

When Colonel Harrington arrived, several overseers were on the ground, injured or shaken. Jacob stood in the middle of the clearing, breathing hard but physically unharmed.

The colonel drew his pistol.

Witnesses later said the silence that followed felt almost unreal.

Then Jacob spoke.

“I’m Not Here Anymore”

His words have been quoted and repeated in various forms, but the core idea is the same:

“I ain’t here no more. You might be looking at me, but I ain’t here. I been gone since that letter came.”

He then turned and walked toward the tree line.

He did not run.

He did not plead.

He did not look back.

The colonel ordered the overseers to stop him. No one moved.

Jacob disappeared into the woods and out of sight.

A Search With No Answer

The colonel launched an extensive search:

-

Twenty-plus armed riders

-

Tracking dogs

-

Coordination with neighboring plantations

-

River and road patrols

The dogs traced Jacob’s scent to a small creek. There, the trail vanished. The hounds could not pick up the scent upstream or downstream.

No body was found.

No scraps of clothing.

No sign of a struggle.

On paper, Jacob simply ceased to exist.

The plantation, however, did not simply go back to normal.

The System Begins to Falter

In the days that followed, three overseers resigned. One wrote that he no longer believed order could be maintained as before. Others turned to drinking or withdrew in fear.

The colonel, troubled and obsessed, investigated further. Eventually, he learned the content of the letter that had reached Jacob.

It had come from Georgia, from Jacob’s wife, who had been sold away from him:

-

She told him she was pregnant

-

She warned him not to attempt a violent rescue

-

She wrote that she knew they might never see each other again

-

She asked him to “stay whole inside,” even if they were separated

The letter, meant to break his spirit, had instead severed his fear. Jacob decided that if he could not control what had been done to his family, he could at least control the choices he made from that day on.

Weeks later, a cloth bundle was found in a hollow tree near the plantation’s boundary. Inside were a wooden carving of two figures, a piece of paper with a Georgia address, an iron tag from his former workplace, and a short note in Jacob’s handwriting. In it, he explained that he was walking—slowly and carefully—toward Georgia. If he made it, no one at Harrington would hear from him again. If he did not, he wanted it known that he had died trying to reach what he loved.

Then he added a line that deeply unsettled the colonel:

“I wasn’t fighting that morning. I was showing you I ain’t a thing you can move no more. You can kill a man like that. But you can’t work him.”

The colonel burned the note.

The enslaved community passed the words along anyway.

A Quiet Idea That Spread

After Jacob’s disappearance, something changed on Harrington Plantation:

-

Escape attempts increased

-

People began quietly refusing to cooperate in certain punishments

-

Groups would stand together, humming or remaining silent, making it clear they were watching

The plantation did not erupt into open revolt. Instead, people began to test the boundaries of what they would accept. The overseers’ authority no longer felt automatic.

By 1858, overseers were leaving regularly. The plantation’s profitability decreased. Eventually, the colonel sold the estate. A new owner tried to restore discipline but faced the same problem: the people no longer viewed themselves purely as objects of control.

Jacob had become a symbol—“the man twelve couldn’t move.”

What Became of Jacob?

Official records provide no clear answer about Jacob’s fate. Some accounts suggest he may have reached free territory in the North. An anonymous testimony published in an abolitionist paper in Philadelphia, written by a man whose details match Jacob’s, includes a striking line:

“I didn’t fight those men. I just decided they couldn’t decide for me anymore.”

Whether he lived long afterward or not, his influence continued.

The Strength That Truly Frightened the System

Jacob Terrell did not single-handedly end slavery. The institution persisted for years after his escape. But on one foggy morning in 1856, he revealed a truth that many slaveholders preferred not to face:

Their power depended on people believing they had none.

The system relied on fear, repetition, and the assumption that resistance was pointless. When one man stopped accepting that assumption, twelve armed overseers, the plantation owner, and even the records in his ledgers could not fully contain what he showed others.

Jacob’s greatest strength was not only physical. It was the quiet decision that he would no longer participate in his own oppression. Once he made that choice, the structure around him began, slowly and silently, to crack.

And that is why, nearly two centuries later, his story still resonates: a reminder that dignity, once claimed, can unsettle even the most rigid systems built to deny it.