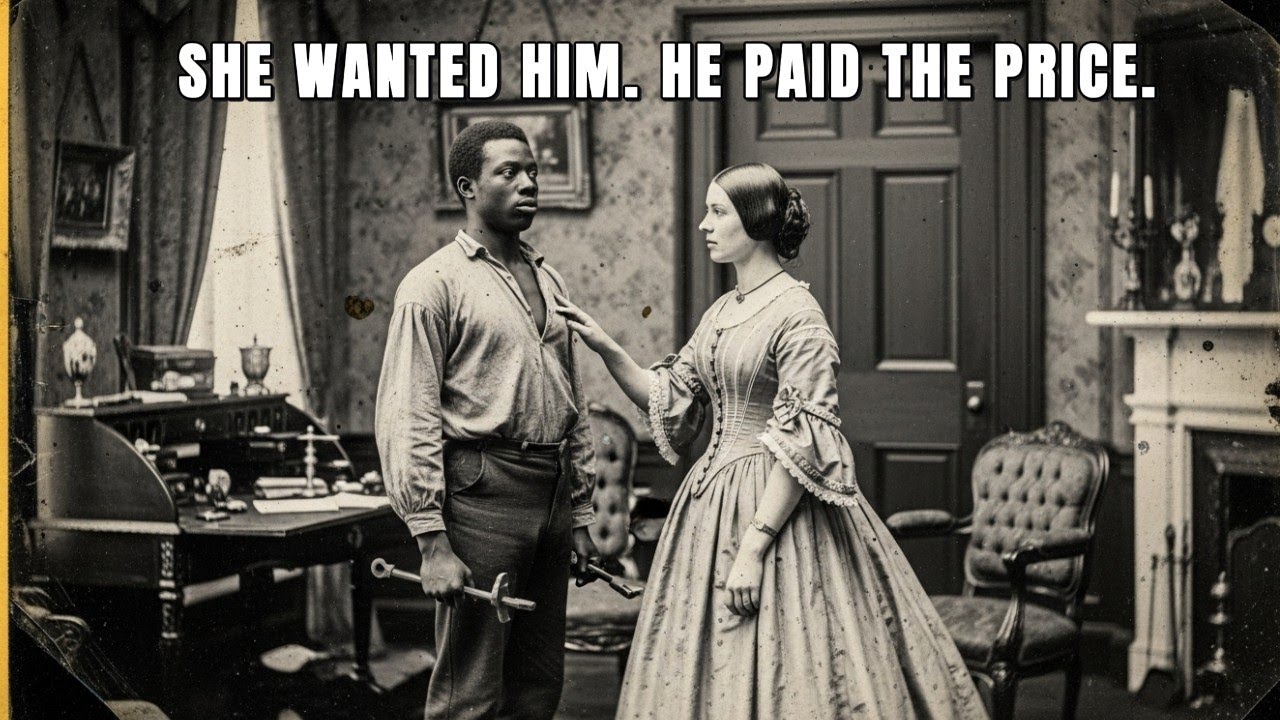

James Rutledge: The Erased Life of an Enslaved Young Man in Antebellum Virginia

Between 1847 and 1849, in the hills of western Virginia, a name quietly disappeared from plantation records.

It belonged to James Rutledge, an enslaved young man listed at $1,200 — a skilled blacksmith’s apprentice, barely eighteen years old.

Two years later, that name was scratched out and replaced with a single, chilling phrase in the ledger:

“Disposed of by arrangement — medical necessity.”

For generations, no one in Greenfield County spoke openly about what that meant. But in fragments of family correspondence, half-burned journals, and oral histories passed quietly from one generation to the next, a different story survived.

According to those traces, James was not sold, and he did not die of illness. Instead, he was subjected to an irreversible medical procedure ordered by his owner — a violent act framed as “discipline” and “protection” of a household’s reputation.

His fate reveals how power, race, and respectability could be used to justify almost anything in the slaveholding South.

The Plantation Behind the Image

In 1847, Belmont Hall stood as a symbol of Virginia wealth and status: hundreds of acres of tobacco fields, grand columns, and carefully cultivated appearances.

Its owner, Marcus Sutherland, considered himself a “modern” planter. He claimed to treat the people he enslaved “humanely,” avoided public whippings, provided better clothing and rations than some neighbors, and lectured others on more “moral” forms of management.

But beneath the polished surface, Belmont Hall rested on the same foundation as every other plantation in the region: the forced labor and total control of human beings. Any kindness existed only within the limits of ownership. At any moment, a life could be bought, sold, relocated, punished, or erased.

Sutherland’s young wife, Arabella Fairchild Sutherland, was twenty-five, educated, and restless. Raised in a declining Charleston family, she had married for stability, not affection. Her husband’s attention soon shifted to ledgers, crops, and his standing among other landowners. She was left with long days, rigid expectations, and little real power—except in one area: the authority she could exercise over the enslaved people around her.

Into this household stepped James Rutledge.

James Rutledge: The Apprentice

James was born enslaved at Belmont Hall in 1829. His mother, Rachel, worked as a seamstress in the main house. Though never recorded in formal documents, family whispers and later research strongly suggest that James’s father was Marcus’s own brother.

This unacknowledged lineage placed James in a complicated position. It afforded him slight privileges—access to training, less grueling field labor—but also made him visible in ways that could quickly become dangerous.

By twelve, he had been sent to learn the blacksmith’s trade. Over the next several years, he developed into one of the most capable young craftsmen in the county. His skill with iron, his calm manner, and his intelligence earned the respect of other enslaved workers and even some white neighbors. His physical presence and quiet dignity made him stand out further.

In the spring of 1847, repairs were needed on Belmont Hall’s east wing. James was assigned to assist with structural and hardware work in and around the main house. It was during this time that Arabella first truly noticed him.

A Dangerous Imbalance

Through parlor windows and hallway encounters, Arabella saw James at work—carrying tools, fixing hinges, lifting beams. In a world where she had little personal agency, the presence of a young man who embodied strength, skill, and composure invited attention she did not fully understand or control.

Later accounts suggest that Arabella’s interest shifted from curiosity to fixation. She began finding reasons to ask questions about the forge, about the heat of the fire, about the tools he used. When her husband left for business in Richmond, she requested James’s assistance in more private spaces of the big house.

What happened during those encounters is filtered through secondhand accounts and heavily biased sources. What is clear, however, is that James understood the peril of his position. In a system where any interaction could be reinterpreted to his disadvantage, there was no truly safe response. If he kept his distance, it could be read as insolence. If he complied with requests, it could be twisted into impropriety.

Within months, quiet fascination turned into something more dangerous: a narrative.

From Whisper to Accusation

Later letters and testimonies suggest that Arabella began shaping a story about James in the surrounding community. Small remarks were dropped in conversations—a suggestion that “a young man in the quarters had forgotten his place,” or that “certain looks” made her uncomfortable.

These insinuations, once released, took on a life of their own. In a white society conditioned to protect reputations and hierarchies, such hints were enough to reshape how people talked about James.

By mid-1847, Marcus began hearing fragments of these stories in town. Viewed through the lens of suspicion, ordinary gestures could now be interpreted as evidence of imagined “disrespect” or “inappropriateness.” The social logic of the time tilted automatically toward the protection of the white household, not the humanity of an enslaved teenager.

Eventually, Arabella went to her husband in tears, according to later family accounts. She claimed that James had behaved improperly toward her and that she had been too ashamed to speak of it sooner. In a world where Black voices were systematically dismissed, her word alone was enough to decide James’s fate.

“Medical Necessity”

Determined to avoid public scandal, Marcus turned not to courts or public punishment, but to the language of medicine—what he regarded as a more “rational” and discreet form of control.

He wrote to Dr. Cornelius Ashby, a Richmond physician known for so-called “corrective procedures” performed on enslaved men accused of moral or sexual misconduct. Ashby specialized in turning brutal punishments into clinical events: instruments, reports, and invoices replacing visible chains.

When the doctor arrived weeks later, he brought surgical equipment, chemicals to dull pain and consciousness, and assistants to carry out the procedure.

On a July day in 1850, James was summoned to a room in the main house. He was told that he had “misconducted himself” toward the mistress of the home and that a medical operation would be performed “to ensure he would never transgress again.”

Records do not preserve James’s full response. But from that moment on, his bodily autonomy was stripped away under the sanction of “science.” He did not choose the procedure; he endured it.

In the physician’s later correspondence, he described the operation as “successful,” and assured Marcus that James would recover and return to work in a few weeks.

On paper, it was labeled a “medical necessity.” In reality, it was a punitive act meant to neutralize a perceived threat, protect a reputation, and maintain control.

A Changed Man

James did survive. His body healed enough for him to return to the forge. But accounts from other enslaved people and household observers note that he was transformed.

The young craftsman who had once carried himself with quiet pride now moved through the plantation with a distant, hollow focus. He worked as he was ordered, spoke little, and avoided eye contact. The operation had not only altered his body; it had also devastated his sense of self and safety.

To the Sutherlands, life returned to its routines. Crops needed tending, accounts needed balancing, guests needed entertaining. In private letters, Marcus characterized the event as an unfortunate but necessary step to “preserve domestic order.”

The system encouraged exactly this kind of thinking: acts of violence reframed as management, trauma renamed as treatment.

Disappearance and Erasure

In March 1853, James was sent into town to collect supplies. He never came back. Hours later, his horse returned to the plantation without him.

Some speculated that he had drowned in a nearby river. Others quietly suggested that he might have used the errand to escape, making his way north toward cities like Philadelphia, or farther, into free territory.

No formal investigation was made. Marcus noted the loss as property gone and moved on. Arabella, according to surviving sources, never asked publicly what had happened to him.

His mother, Rachel, refused to accept the idea of his death without proof. Until the end of her life, she reportedly told those who would listen, “My boy is alive. Somewhere, he is alive.”

After the Civil War and emancipation, the Sutherland family destroyed many of their papers. Arabella’s journals were burned at her request. “History,” she is said to have remarked, “is what we choose to remember and what we choose to forget.”

What remained of James’s story were scattered traces: a ledger note about “medical necessity,” a physician’s cautious letter, and fragments of memory passed down through descendants of both the enslavers and the enslaved.

Unearthing the Hidden Record

In 2003, genealogist Dr. Ellen Forrester was hired by Sutherland descendants to help trace their family tree. While combing through archives, law firm basements, and regional records, she found references that pointed toward an unsettling, long-suppressed story.

Piecing together the plantation ledger, Ashby’s preserved letter, and oral accounts from families connected to Belmont Hall, she reconstructed the core of James Rutledge’s experience.

In her report, she described his life as a window into “the intimate violence of slavery—where control over another person’s body could be enforced not only through overt punishment, but also through procedures cloaked in medical language and social respectability.”

The findings divided the family. Some believed a memorial or historical marker should acknowledge what had been done. Others preferred silence, arguing that the past should remain buried.

No formal monument was erected in James’s name.

Why His Story Matters

Today, Belmont Hall no longer stands. The house burned in 1923, and a state highway now covers much of its former land. A roadside plaque marks the site’s “economic importance” to the tobacco industry, but it makes no mention of the lives shaped and broken there, including that of James Rutledge.

Yet his name survives in scattered documents and research. His story illustrates how a young man’s life could be altered—or erased—by the combination of racial hierarchy, gendered expectations, and the desire to preserve appearances at all costs.

James was eighteen years old. He was a craftsman, a son, a person with skills and a future that should have extended far beyond the boundaries of one plantation. His greatest “offense” was existing within reach of power he could neither challenge nor escape.

Remembering his story is not about revisiting pain for its own sake. It is about acknowledging how systems once turned human suffering into paperwork and policy—and how easily a life could be written out as “disposed of by arrangement.”

Until names like James Rutledge are spoken, recorded, and recognized, the historical record remains incomplete, and the silence that once covered such lives continues, unchallenged.