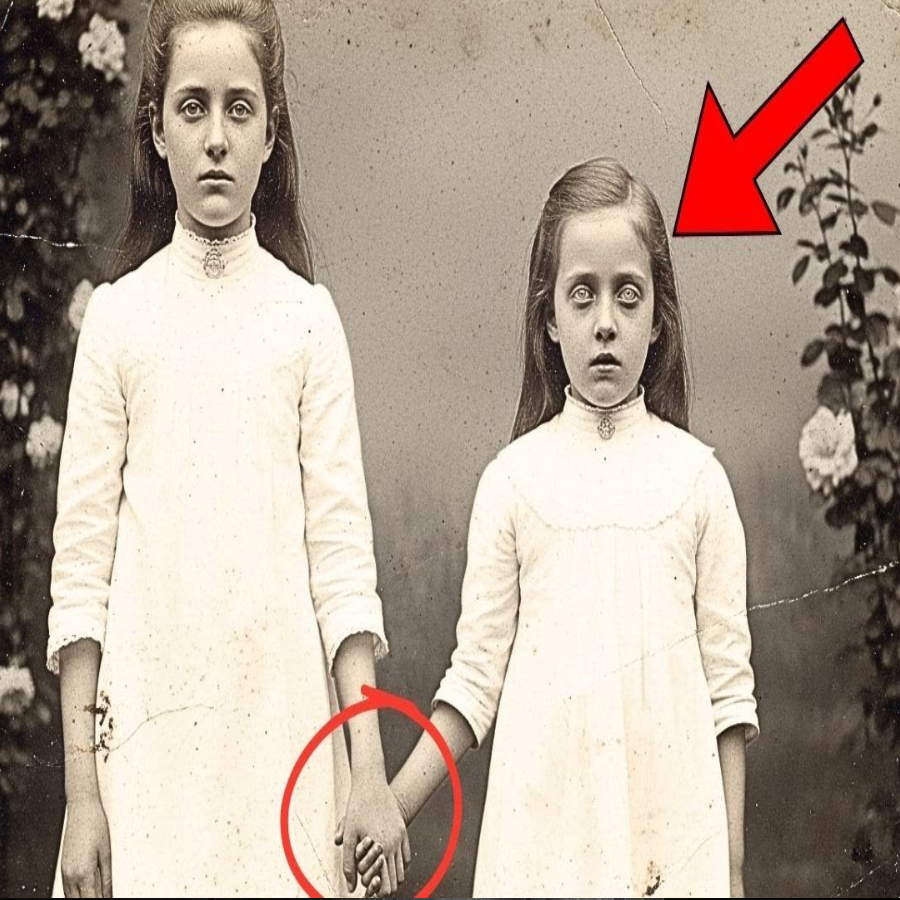

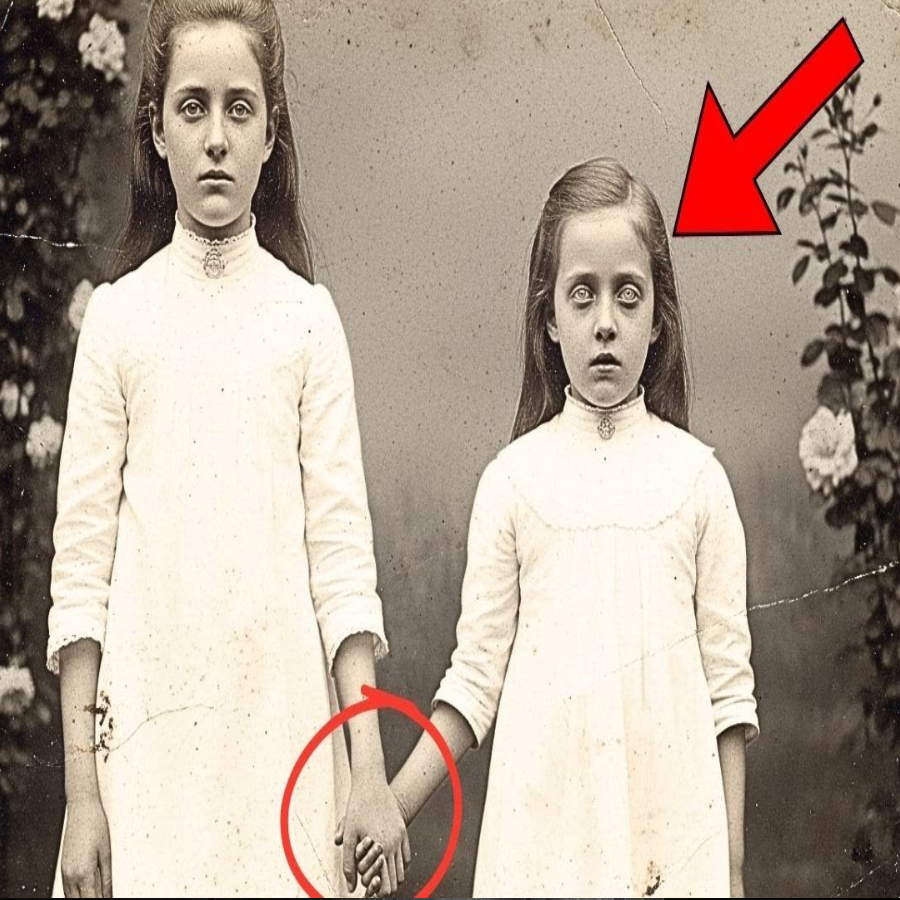

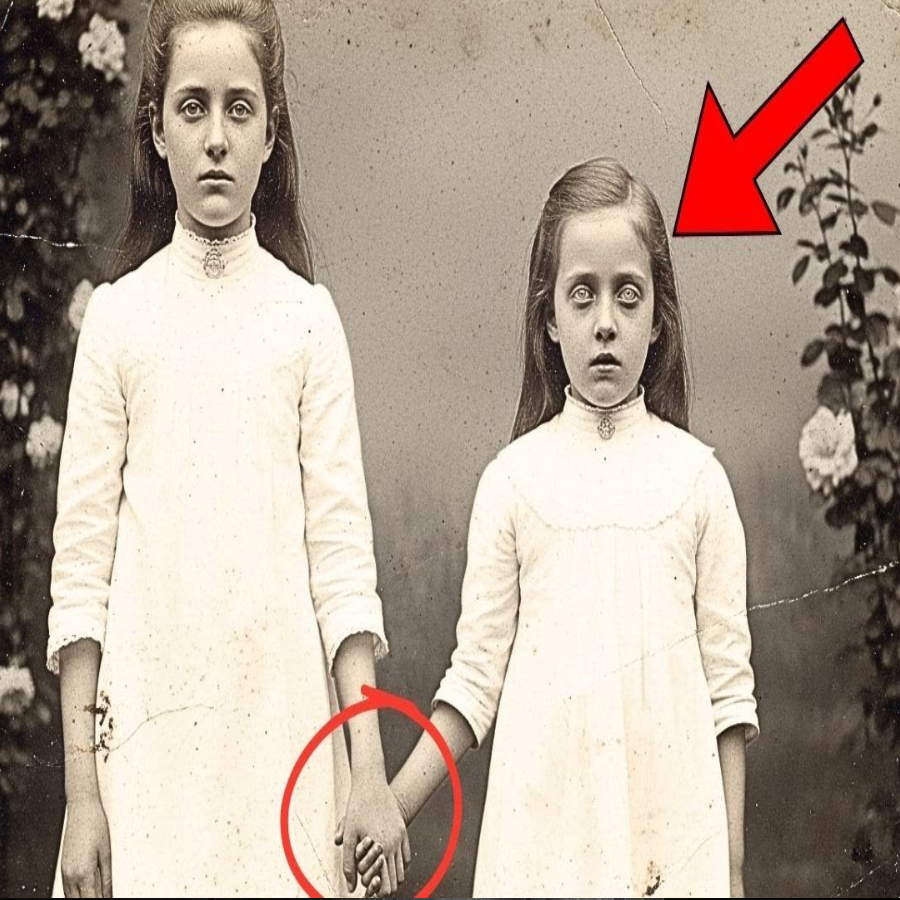

When museum curator Dr. Helen Foster examined this 1895 photograph in 2021, she initially saw what everyone else had seen for more than a century. Two sisters in identical white dresses stood hand in hand in a garden, their expressions serious in the familiar, composed style of the Victorian era.

The picture had been donated anonymously to the Boston Historical Society with only a brief handwritten note attached: “The Davy’s sisters, 1895. May they finally rest.” Helen was close to filing it away without much thought when something about the younger girl’s hand caught her attention. The way the fingers bent, the slightly strained position, looked off. She requested a high-resolution scan. What the digital restoration revealed helped her understand why the photograph had been kept out of sight for more than 100 years, and why the note ended with the words, “Finally, rest.”

This was not simply a portrait of two sisters. It was an image of a promise that continued beyond one child’s life. The photograph reached the Boston Historical Society on March 15, 2021, inside a plain manila envelope with no sender listed.

Inside was a single sepia-toned print, roughly 5×7 inches, mounted on thick cardboard backing typical of late-19th-century studio work. The photo showed two girls standing in what appeared to be a garden. The older child, around ten or eleven, stood on the left in a white Victorian dress with a lace collar and puffed sleeves.

Her dark hair was pulled straight back from her face in a strict style. Her expression was solemn, almost heavy, as if she carried more than a child’s share of worries. Next to her stood a smaller girl, perhaps six or seven years old, also wearing white. She was shorter and slighter, with the same dark hair and serious features. The younger girl’s right hand was clasped tightly in the older girl’s left. Their fingers were firmly interlaced.

Behind them, a trellis covered in climbing roses formed the backdrop. The gentle, diffused light suggested the picture had been taken outdoors, which was somewhat unusual for the period, when most portraits were composed in studios with controlled lighting. Along the bottom of the cardboard mount, in faded brown ink, were the words, “Lily and Rose Davies, June 1895.”

The accompanying note, written on modern paper in a shaky, elderly hand, read, “The Davy’s sisters, 1895. May they finally rest. I can’t keep this any longer. Someone should know the truth.”

At 52, Dr. Helen Foster had spent 18 years as curator of the photographic archives at the Boston Historical Society. She had examined thousands of Victorian portraits.

At first glance, this image seemed typical: a formal photograph of children from a well-off family, the kind of carefully posed portrait that filled archives around the country. Yet something about it unsettled Helen. She could not immediately put her finger on what was wrong. She picked up a magnifying glass and studied the image more closely.

The older girl—Lily, according to the inscription—looked straight into the camera lens. Her expression was hard to categorize: not clearly sad, not clearly angry, but something closer to acceptance, or perhaps a quiet resolve. The younger child, Rose, had her head tilted slightly toward her sister. Her gaze was also directed toward the camera, but her eyes appeared somewhat unfocused, lacking the usual spark.

Her mouth was parted just a little, and that was when Helen’s attention returned to the hand. Rose’s hand, the one Lily was holding, had a strange quality. The fingers were curled in an odd way, not quite matching natural muscle tension. The skin tone of the hand looked slightly different from the rest of the visible skin—darker, perhaps, or uneven in a way the sepia tint could not completely conceal.

Helen took out her measuring tools and examined the print’s size, mounting, and materials. Everything matched the techniques and standards of photography from 1895. The image was clearly not a modern fabrication. But there was still something about it that felt wrong, something she could not yet define. She decided the photograph needed to be scanned at the highest possible resolution.

The society had recently purchased a new scanner capable of capturing detail at 12,800 dpi—fine enough to reveal elements invisible to the naked eye, details that original Victorian viewers, and even the photographer, would never have noticed. The scan was scheduled for March 18, three days later. Helen placed the photograph carefully in an archival storage box and tried to move on to other tasks. That night, however, she dreamed about it.

In her dream, the two girls from the photograph were standing in her office. The older girl, Lily, was silently crying. Rose, the younger, stood perfectly still—no blinking, no visible breathing. Lily kept repeating the same sentence, over and over. “I promised. I promised I’d never let go. I promised.”

The high-resolution scan took four hours to complete. Helen stood in the society’s digital lab with Marcus Chen, the imaging specialist, watching as the scanner’s sensor array slowly recorded the photograph. The machine captured not only the visible image but also infrared and ultraviolet data that could reveal hidden writing, retouching, or damage not noticeable under normal light.

When the scan finished, Marcus loaded the file onto his workstation. The photograph appeared on the large 4K monitor with extraordinary clarity. Every grain of the emulsion, every tiny scratch on the mount, every fiber of the paper became sharply visible.

“Let’s start with an overall check,” Marcus said, zooming in to 200 percent. “This looks authentic—definitely late-19th-century paper and emulsion. I’m not seeing anything that suggests modern editing or tampering.”

Helen leaned closer. “Can you zoom in on the younger girl—on her hand?” she asked.

Marcus enlarged Rose’s right hand, the one clasped in Lily’s. At 800 percent magnification, details emerged that could not have been seen otherwise. The texture of the skin looked different. While Lily’s hand showed the fine lines and surface features of living skin, Rose’s appeared smoother, with a wax-like quality. The fingers, which had only seemed oddly placed at normal size, now clearly looked stiff, held in position by something other than muscle.

“That’s post-mortem lividity,” Helen said softly. “The darker discoloration—signs that the child had already passed away when this was taken.”

Memorial photography after death had been a known practice in the Victorian era, but those images were usually clearly identified as such: children posed in beds or cradles, often surrounded by flowers, the stillness of their faces unmistakable.

This photograph was different. It had been composed to give the impression that both children were still alive.

Marcus switched to the infrared layer of the scan. Under infrared, living and non-living tissue reflect light differently. The distinction between Lily and Rose became sharply defined. Lily’s body showed patterning consistent with the way a living subject’s form could register in a photograph, traces preserved in the emulsion even after more than a century.

Rose’s body showed no such pattern. There was only a uniform reflection, lacking the subtle variations visible in Lily’s form.

“The older girl was alive,” Marcus said. “The younger one had already passed. Given the visible discoloration at this resolution, I’d say she had been gone at least several days, possibly up to a week.”

A chill ran through Helen.

“Show me their faces,” she said. “As close as you can.”

Marcus enlarged Rose’s face to 1,600 percent. The effect was heartbreaking. What had looked like a slightly unfocused gaze at normal size now revealed itself as clouded eyes. The corneas showed the milky opacity that develops some hours after death.

Her slightly open mouth revealed just the tip of her tongue, which appeared darker and dry. Yet what struck Helen most was the cosmetic effort. At this magnification, she could see someone had carefully applied powder and rouge to Rose’s face to give her cheeks a hint of color. Rose had been positioned with great care to minimize visible signs of death.

Someone had worked very hard to make her appear alive.

Marcus then zoomed in on Lily’s face. At this level of detail, tiny details stood out: faint moisture around her eyes, the trace of tears barely noticeable before. Lily had been crying at the time of the exposure. The rims of her eyes were slightly red, and faint tear tracks ran down her cheeks beneath the powder she, too, was wearing. And there was something else—writing along the mounting board just below the photograph.

It was so faint it could not be seen without enhancement. Marcus adjusted contrast and sharpening. Gradually, words appeared. They were written in pencil, in a child’s hand: “I promised Mama I would hold her hand forever. I kept my promise. June 12th, 1895.”

Helen began searching for information on the Davies family immediately.

Locating detailed records from 1895 was not easy, but the Boston Historical Society had extensive collections and access to genealogical databases. Within two days, Helen had traced them. The Davies family had lived in Boston’s Beacon Hill neighborhood. The father, Robert Davies, was a successful textile merchant. The mother, Eleanor Davies, came from an established Boston family.

They had two daughters: Lily, born March 1884, and Rose, born September 1888. Records showed that Rose Davies died on June 3, 1895, at the age of six years and nine months. The listed cause of death was scarlet fever. Lily Davies died seven days later, on June 10, 1895, at age eleven years and three months, also from scarlet fever.

The photograph was dated June 1895, meaning it had been taken sometime between Rose’s death on June 3 and Lily’s death on June 10. Helen found both death certificates in the Massachusetts State Archives. The records showed that both girls were buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery on June 11, 1895, in the family plot. Their funeral service was held at Trinity Church. But one detail in the burial records stood out.

For Rose’s burial entry, a note read, “Delayed interment due to family circumstances. Body held at family residence June 3–10.”

Rose’s remains had stayed in the family home for seven days before burial. According to weather records, temperatures in Boston that week reached the mid-80s. Helen uncovered a Boston Globe article dated June 12, 1895.

Its headline reported tragedy in the Davies household: both daughters lost to scarlet fever. The article described a prominent Beacon Hill family, Robert and Eleanor Davies, mourning the loss of both daughters within one week. Rose, age six, had passed away on June 3. Her older sister Lily, age eleven, fell ill soon after and died on June 10.

Sources quoted in the piece said Lily had refused to leave her sister’s side during Rose’s illness and insisted on staying with her even after Rose died. The article noted that the funeral had been held the previous day at Trinity Church and that Mrs. Davies was described as overwhelmed by grief and under medical care.

Helen cross-checked the information with city health records and discovered more. On June 8, 1895, a physician named Dr. Samuel Morrison had been called to the Davies residence after neighbors raised concerns. His report, filed with the city health department, read that he had responded to a welfare complaint at 44 Beacon Street.

He found the surviving child, eleven-year-old Lily Davies, refusing to be separated from her deceased sister’s body. Lily had reportedly said she had promised her mother she would stay with Rose. Both parents were described as ill—Robert recovering from scarlet fever and Eleanor in a state of collapse from grief. Dr. Morrison recorded that Lily had been sleeping beside her sister’s body for five days.

Despite health concerns, the family had declined immediate burial. The doctor recommended urgent intervention, but none was carried out. Rose’s body remained in the house for two more days.

During that week, someone arranged for a photographer to visit the home. Someone dressed the two girls in matching white dresses and posed them together in the garden, hands clasped. Someone instructed Lily to look at the camera and try to remain composed.

The result was a photograph that presented both Davies sisters together one last time, as though they were both still alive.

Helen’s research next took her to the archives of the Boston Photographers Guild, where records of professional photographers active in 1895 were kept. One name appeared in connection with the Davies family:

Thomas Blackwell, a photographer known for memorial portraits after death. His business ledger, preserved in the society’s collection, included an entry dated June 7, 1895: “Davies residence, 44 Beacon Street. Memorial portrait. Two subjects. Special arrangements. Payment $50.” Fifty dollars in 1895 was a substantial amount, equivalent to roughly $1,800 today, and significantly more than a typical memorial photograph fee.

Helen sought more information on Blackwell and discovered that his personal diary had been donated to the society in 1957 by his granddaughter. She requested the volume, and when it arrived, she carefully turned to the pages for June 1895. The June 7 entry was longer and more detailed than most.

He wrote that he had received an urgent request to come to the Davies home on Beacon Hill. The situation there, he noted, was among the most troubling he had seen in two decades of memorial photography. The younger daughter, Rose, had died of scarlet fever four days earlier. The older daughter, Lily, had also contracted the illness and, according to the family doctor, was not expected to survive for long. But what unsettled him most was Lily’s behavior.

She refused to leave her sister’s side. She slept beside the body, held the dead child’s hand, and spoke to her as if she were still alive. The mother was overcome with grief, and the father was weak from illness. They had called him because Lily herself had requested it.

The child wanted a photograph of herself with her sister “so Mama can remember us together,” he wrote. He explained that he tried to suggest a traditional memorial portrait, but Lily became extremely distressed. She insisted the photograph must show both girls as if they were alive together. She asked him to promise he would pose them so that Rose’s condition would not be obvious.

Blackwell described feeling deeply uneasy about the request, but noted that Lily was dying and her parents were in no state to refuse her anything. He agreed to proceed.

He wrote that he photographed the two girls in the garden, positioning them so Rose’s condition would be as concealed as possible. He arranged them holding hands, as Lily demanded. Lily, he wrote, cried throughout but tried to stay still during the exposure. She spoke softly to her sister the entire time, asking her to stay calm and still just a little longer. Rose, of course, did not move at all.

He completed the sitting within half an hour and left quickly. The father paid him double his usual rate and begged him never to speak of the session. Blackwell recorded that he would keep their confidence, but that he would never forget the sight of a living child clinging to her deceased sister’s hand, trying with all her strength to act as though nothing had changed, trying to keep a promise that no child should ever have to bear.

Helen leaned back from the diary, her hands unsteady. The photograph now had a context.

This was not an attempt to deceive the public. It was a final gift from a dying girl to her grieving parents—a deliberate illusion created out of love. Lily understood she was dying. She understood that this photograph would likely be the last thing she could do. She chose to use that moment to create a picture where, for a brief, frozen instant, both Davies sisters appeared together, alive and whole.

Lily Davies died three days after the photograph was taken. Helen located her death certificate and associated medical notes. Dr. Morrison wrote that Lily’s condition declined rapidly after prolonged close contact with her deceased sister. Scarlet fever had been made worse by exhaustion and overwhelming grief. He recorded that Lily had refused food and water during her final 48 hours. Her last recorded words were, “I kept my promise.”

Lily was buried beside Rose on June 11, 1895. The joint funeral drew over 200 attendees. The Boston Globe reported that Eleanor Davies, the girls’ mother, collapsed during the service and had to be carried from the church.

Helen then searched for records describing what became of the parents afterward.

The documents she found were deeply sad. Eleanor Davies never fully recovered. In August 1895, she was admitted to an asylum, diagnosed with acute melancholy and severe nervous exhaustion. She spent the next 12 years there, largely unresponsive, reportedly spending much of her time gazing at a photograph she kept in her room.

According to the asylum records, it was a photograph of her two daughters in white dresses, holding hands—the same image Helen had been studying. Robert Davies sold the Beacon Street house in September 1895. He relocated to New York in an effort to rebuild his life. He remarried in 1899, though the marriage lasted only a short time. His second wife left, citing his ongoing focus on the past.

Robert died in 1904 at the age of 49 from heart failure. His obituary mentioned his first family only briefly, noting that he had been preceded in death by his daughters Lily and Rose and his first wife, Eleanor.

The photograph’s story did not end there. Helen traced its path through the family over the decades.

After Eleanor’s death in 1907, her few belongings were sent to her sister, Margaret Hartwell, from whom she had been estranged for years. Margaret reportedly understood at once what the photograph showed. In her diary, she wrote that Eleanor had kept the picture in her asylum room for 12 years, staring at it for hours and whispering to her daughters.

Margaret noted that she now understood why: in the image, Lily was still alive, but Rose had already passed. Eleanor had spent those years looking at the brief interval when she still had one child left and could almost imagine that both were still with her. Margaret called it a painful kind of comfort. She wrote that she could not keep the photograph because it was too distressing, but she also could not bring herself to destroy it, as it was all that remained of the children.

Margaret placed the photograph in a trunk, where it stayed for 50 years until her death in 1957. Her daughter Catherine inherited it and kept it out of sight, never showing it to anyone. When Catherine died in 1998, the photograph went to her son, James Hartwell, then 73. It was James who finally sent it to the historical society in 2021.

Helen located him through genealogical research and spoke with him by phone.

“I’m 94 years old,” James told her, his voice frail but steady. “My mother told me about that photograph when I was young. She said it wasn’t cursed in the usual sense, but that it carried a heavy kind of love. She said it showed what love becomes when it cannot let go, even when letting go might be kinder.”

He explained that he had kept the photograph for 23 years since his mother’s death. “I’m ill now—cancer,” he said. “I don’t want my children to inherit this responsibility. Let history take care of it. Let someone else remember those girls.”

He died two weeks after mailing the photograph. His obituary did not mention the Davies sisters or the image at all.

In April 2021, Dr. Helen Foster presented her findings to the Boston Historical Society’s board. The reaction was mixed. Some members believed the photograph should be displayed as a valuable historical artifact, illustrating Victorian attitudes toward illness, grief, and childhood.

Others felt it was too sensitive and too personal for public exhibition. They argued that showing it casually might ignore the pain woven into its history. Helen proposed a compromise: preserve and document the photograph thoroughly but keep it in restricted access. Allow researchers to study it under appropriate conditions, but do not present it as a standard museum display. Honor the story it carried.

The board agreed. The photograph was cataloged, scanned, and placed in the society’s restricted archives. A detailed file was created summarizing everything Helen had uncovered about the Davies family.

Yet Helen could not stop thinking about the faint inscription: “I promised Mama I would hold her hand forever. I kept my promise.” She wondered what exactly Lily had promised. When she revisited the medical records, she found a detail she had originally overlooked.

Rose Davies had been sick for three weeks before she died. During that time, Dr. Morrison’s notes recorded that Lily refused to leave her sister’s bedside. In an entry dated May 28, 1895, six days before Rose’s death, he wrote that Lily had also contracted scarlet fever but insisted on staying with Rose, despite the risk to her own health.

When he tried to separate them, Lily became extremely upset. She said she had promised her mother that she would hold Rose’s hand until “everything is better.” In her distress, Eleanor allowed this arrangement to continue. Dr. Morrison wrote that he feared both children would be lost.

The promise had not originally been about death at all. It had been about comfort.

In her desperation, Eleanor had asked Lily to stay with Rose, to hold her hand, to give her reassurance while she was ill—until things improved. Lily, still a child herself, took those words literally. She held Rose’s hand while her sister was sick. She continued to hold it after Rose passed away. She kept holding it during the seven days Rose’s body remained at home, and she insisted on a photograph showing her still keeping that promise, even though “better” would never come.

Helen discovered one more document that moved her deeply: a letter written by Eleanor Davies while in the asylum, dated 1901, preserved in the institution’s records.

In the letter, addressed to Lily, Eleanor wrote that she should never have asked her daughter to make such a promise. She wrote that Lily had taken her careless words and turned them into a duty that ended her life. She acknowledged that Lily had stayed when she might have been protected, had shared the same air as her very ill sister, and had worn herself out caring for Rose. When Rose died, Lily could not let go, because she believed she was still bound by her promise to her mother.

Eleanor wrote that she lived every day with the belief that she had lost both children—one to disease and one to love that carried a terrible cost. She described the photograph as a constant reminder of the moment of Lily’s sacrifice: Lily standing there, already ill, pretending for her mother’s sake that everything was still normal, pretending that Rose was still alive, creating one final comforting illusion so her mother would not be left with only painful memories.

She ended the letter by apologizing to Lily, asking for forgiveness, and asking her to rest.

The letter was never sent. It was found in Eleanor’s room after her death, addressed but not sealed.

Today, the photograph remains in the archives, a record of a promise honored at great personal cost—a memorial not just to loss, but to the weight of love that cannot let go. When Helen looks at it now, she no longer sees it as a simple act of concealment.

She sees a child trying to shield her mother from unbearable reality. She sees devotion that stretched across illness, loss, and time. She sees what love can become when it refuses to surrender, even in the face of what cannot be changed. The photograph stays sealed in the restricted collection.

Some stories of love and grief are considered too intense for public display. And yet, like this one, they continue quietly in the background, part of the hidden history behind some of the most moving stories the past has left behind.