Georgia, 1860. The land was thick with cotton and secrets, stretching for miles beneath a sky heavy with humidity and history. Harrow Plantation sat at the center of it all, its white columns gleaming in the morning sun, a monument to the kind of wealth built on other people’s unpaid labor and quiet suffering. Silas Harrow, the plantation owner, woke each day to the scent of fresh eggs and bacon, the clink of silverware on porcelain, the easy comfort of a life untouched by hunger. He ate like a king—roasted meats, sweet wine, bread so soft it seemed to melt on the tongue. But outside the big house, in the shadows of the fields, reality looked very different.

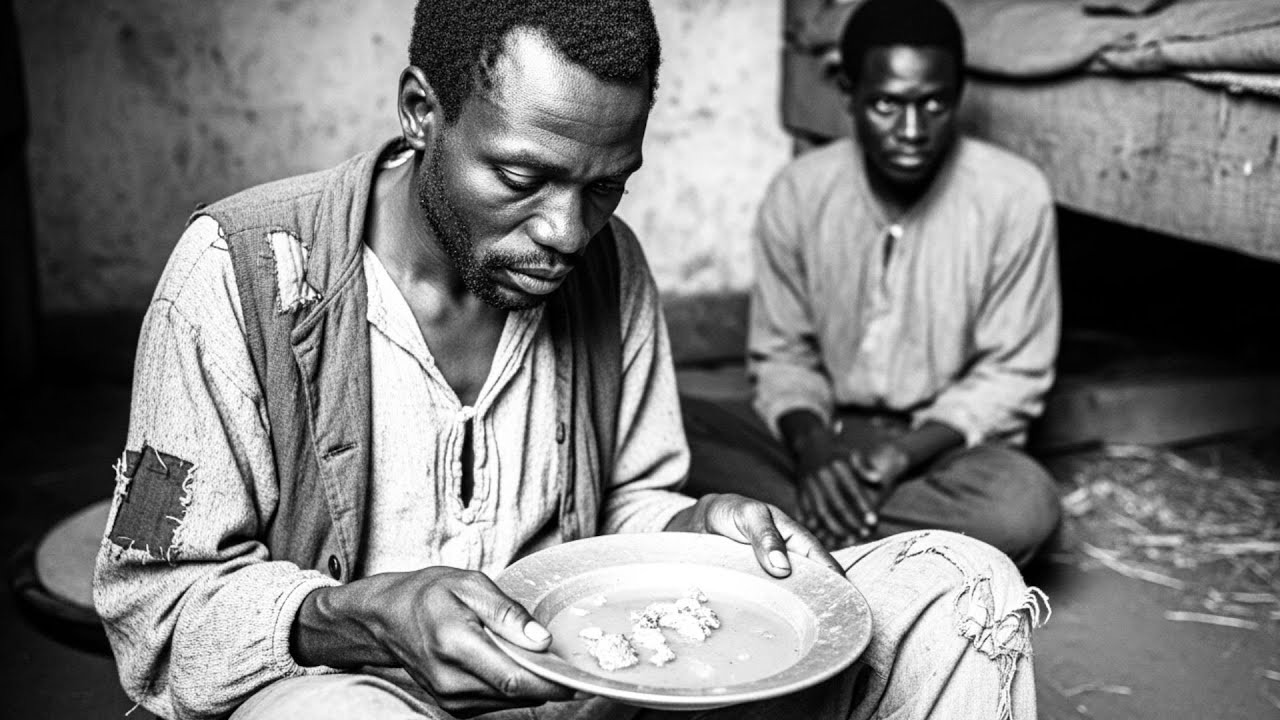

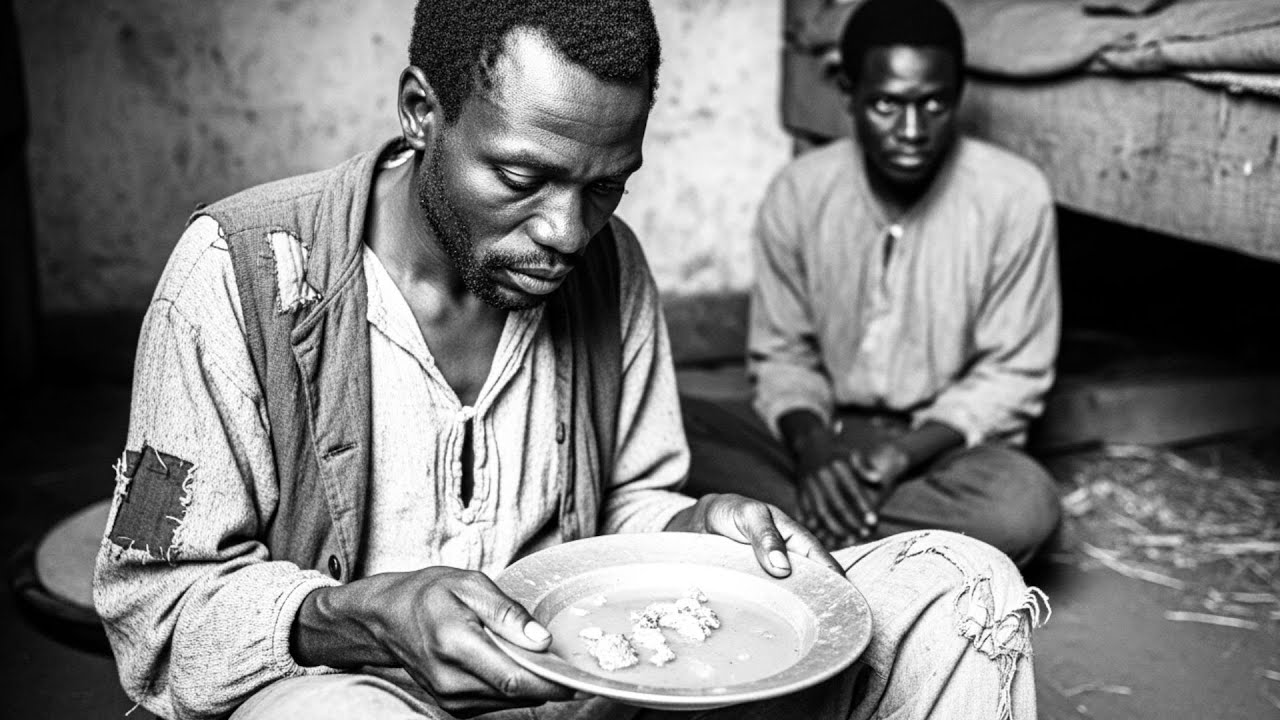

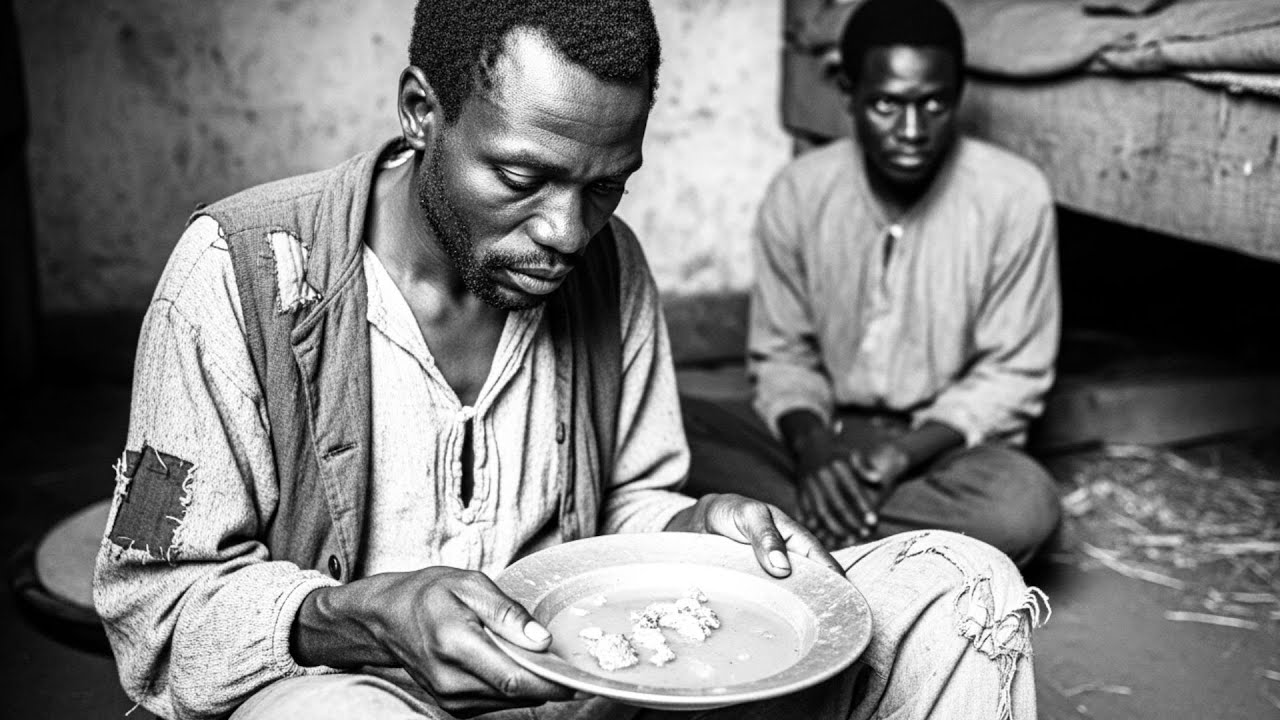

The enslaved people ate from a barrel. Not a clean one, not food meant to nourish, but whatever was left after the household had taken its fill—spoiled corn, scraps of meat on the edge of going bad, a thick sour broth that smelled wrong even from a distance. Silas called it “rations” and believed anything better was wasted money. “A hand doesn’t need good food,” he told his guests. “A hand needs to work.” For five years, that was the rule. The owner dined well, the people in the quarters endured. No one outside questioned it. No one inside dared challenge it. That was simply how things were on Harrow Plantation.

Until one night, everything shifted.

It started with exhaustion, not revolt. A young field hand spilled some of the barrel stew on the cabin floor. Silas saw not weakness, but disrespect. He grabbed his whip and, without overseer or guard, stormed toward the quarters, eager to make an example about “waste.” He walked into that cabin certain of his control. Thirty minutes later, someone ran to the big house screaming for help. They found Silas on the floor—pale, shaking, eyes full of a fear no one had ever seen on his face. What had happened in that small room? And why did no one rush to stop it?

The answer, whispered through generations, involved a man more than seven feet tall who never forgot a single meal.

Silas Harrow had not invented cruelty. His father had practiced it before him, and his grandfather before that. Hardness was the family business, passed down with the land itself. When he inherited Harrow Plantation in 1855, it was 300 acres of prime Georgia cotton, a big house with twelve rooms, forty-two enslaved people—everything a man of his station was told he needed to be “successful.” At thirty-two, Silas was determined to prove he could run the place better than his father ever had—more profit, less “waste,” maximum efficiency. The first thing he changed was the food.

His father had fed the quarters adequately. Not well, but decently enough—cornmeal, salted pork, vegetables from the garden. Basic fare that kept people on their feet. Silas looked at those costs and saw an opportunity. “Why am I spending good money feeding people who don’t produce enough to justify it?” he asked his wife one evening over dinner. She did not answer. She had learned not to respond when he spoke about management.

Silas began experimenting. Portions shrank. Quality dropped. He bought the cheapest corn he could find, often stale or infested. Meat that other plantations refused—pieces that were going off, cuts no one else would serve. When supplies arrived already spoiled, instead of sending them back, Silas had them carted straight to the quarters. “They can eat it or go hungry,” he said. “That’s their choice.”

The overseer, Cotton, who had worked for Silas’s father, tried once to object. “Sir, some of this meat is bad. It’ll make people sick.”

“Then they’ll learn to eat faster before it turns,” Silas replied. Cotton never raised the subject again.

Within six months, Silas had cut food costs by seventy percent. He was proud of the number. He wrote it in his ledger in careful ink, mentioned it to other planters after church. Some shifted uncomfortably. Others nodded, impressed. One man pulled him aside afterward.

“You feeding your people enough to keep working?” the man asked quietly.

“They’re working, aren’t they?” Silas answered.

“For now. But hungry folks get ideas. Dangerous ideas.”

Silas laughed. “My people know their place.”

The other man didn’t laugh. He just looked at Silas with something that might have been warning—or pity.

Every owner thinks that right up until the day he doesn’t.

The barrel system started in 1857. Silas had been running the plantation two years, his profit margins were excellent, but he wanted more. He was always looking for one more corner to cut. That’s when the idea came—one big batch of “food” each day. All the scraps, stale corn, unwanted meat, and kitchen waste would go into a single barrel. Water would be added to stretch it. The mixture would be stirred into a thick stew and ladled out twice a day.

“It’s more efficient,” he explained to Cotton. “Less waste, easier to hand out, one barrel instead of forty-two separate portions.”

“It’s also not fit for people,” Cotton muttered, low enough that Silas pretended not to hear.

The barrel was huge, big enough to hold twenty gallons. It sat outside the largest cabin, and twice a day people lined up with whatever they had—cups, bowls, hollowed gourds. They held out their containers and received a scoop of gray-brown liquid that smelled sour and heavy. Children cried when told to eat. Adults forced it down because the alternative was going without. Some fell ill—stomach cramps, fevers. One elderly woman passed after several days of sickness. Silas insisted it was “her age,” not the food. The people in the quarters called the barrel “Silas’s gift.” When they said it to his face, it sounded respectful. When they said it to each other, the bitterness was clear. But they ate from it every single day, because there was no other choice.

Silas watched this system run for three years. Three years of maximum gain at minimum cost. Three years believing he had found the perfect solution. He never noticed that one man watched him back.

Jedediah arrived at Harrow Plantation in 1857, the same year the barrel appeared. Silas bought him at an auction in Savannah for less than he’d expected to pay. The auctioneer had been almost apologetic.

“He’s strong as an ox, but he don’t talk much. Makes folks uneasy. Previous owner said he was trouble, though I ain’t sure what kind.”

Silas looked up at Jedediah on the block. The man was enormous, over seven feet tall, shoulders like a bull, arms thick as posts. His skin was dark as midnight. His face gave nothing away. His eyes seemed to see everything and nothing at once.

“He looks perfect to me,” Silas said, and bought him on the spot.

Jedediah was sent straight to the cotton fields. He worked without complaint. He picked more cotton than any two men together. He never talked back, never caused problems, never even met a white man’s gaze. He seemed like the ideal field hand.

But Jedediah was always watching.

He watched Silas eat breakfast on the big house porch—eggs and bacon and fresh bread with butter, coffee with real sugar, fruit preserves from the kitchen. He watched the barrel being filled each morning with stale corn and castoff meat and water from the pump. Watched the heavy stew being stirred with a wooden paddle. Watched people line up, watched children make faces, watched elders swallow carefully. He watched the old woman weaken and fade after three days of fever. And he remembered it all.

Jedediah had a gift for memory. He could recall every face he’d ever seen, every word he’d ever heard, every taste, every smell. His mind was like a ledger that never lost a number. He remembered the first spoonful of barrel food he ever tasted—the heavy texture, the sour tang, the way his stomach tightened afterward, and how he had to force himself not to bring it back up because wasting food meant punishment. He remembered the second spoonful, and the third, and the hundredth, and the thousandth. Three years of eating from that barrel. Two servings a day. More than two thousand meals of something that barely deserved to be called food. Jedediah counted every one.

Others in the quarters sometimes talked about running, about fighting back, about burning the big house or slipping something into the owner’s dinner—or a dozen other ideas that stayed mostly as talk, because the price of failure was too high and the chance of success too small. Jedediah never joined those conversations. He just listened and worked and ate from the barrel and counted. He was waiting for something, an opening, a moment when the mathematics of risk and reward finally balanced. He didn’t know when that moment would come, but he knew he’d recognize it when it did.

In the big house, Silas’s wife Martha worried about her husband—not because of how he treated the people on the place. She’d grown up among plantations. That life felt “normal” to her. She worried because he was changing in other ways. He had once smiled occasionally, once joked with guests, once seemed like a man enjoying his own prosperity. Now he was obsessed with numbers, costs, ledgers. He spent hours in his study tightening every line.

“You’re becoming your father,” she told him one night.

“My father died broke,” Silas snapped. “I won’t make that mistake.”

“Your father died with friends and respect. What will you die with?”

Silas didn’t answer. He just turned back to his books. Martha stopped trying after that.

She focused on managing the house, on keeping appearances pleasant when visitors came. But she knew something under the surface was wrong. She could feel it in the air. In the way the house staff moved around Silas, careful and quiet. In the way Cotton sometimes looked at her with something like warning. Something bad was coming. She didn’t know what, didn’t know when, but she felt it approaching the way you feel a storm roll in before the first thunder.

In the kitchen, an older woman named Ruth held things together. She had been cooking for the Harrow family for thirty years. She had cooked for Silas’s father. She had cooked for Silas when he was a boy. She knew every recipe, every preference, every secret pinch of spice—and she knew exactly what went into that barrel every single day.

When Silas started the barrel system, Ruth was the one who had to prepare it. Every morning, she gathered up the scraps, the stale bits, the things no one else wanted. She dumped them into the barrel. She added water. She stirred it until it became the thick, heavy mixture that fed nearly four dozen people. She hated every minute of it. But she did it because refusing meant punishment, or being sent away, or worse. Because she was old and tired. Because she did not see another choice.

Then one day, Jedediah came to the kitchen.

He didn’t speak at first, just stood in the doorway, so tall his head nearly brushed the frame. Ruth looked at him and felt something strange. Not fear, exactly. Recognition. Like looking at a knife and knowing sooner or later, someone would use it.

“What you want?” she asked.

Jedediah stepped inside. He looked around at the pots and pans, at the fresh food set aside for the big house table, at the barrel waiting in the corner. Then he looked at Ruth—really looked at her. When he spoke, his voice seemed to come up from the ground.

“I want you to keep some back,” he said.

Ruth frowned. “Keep what?”

“The worst of it. The most spoiled, the most gone. Don’t throw it away. Hide it. Put it somewhere safe.”

“Why?”

Jedediah didn’t answer directly. He just held her gaze with eyes that carried three years of counting. Three years of waiting. Three years of watching Silas feast while the quarters lived off refuse. Ruth understood more than his words said.

“That’s dangerous,” she said quietly.

“Yes.”

“Could get us both killed.”

“Yes.”

Ruth thought about her seventy years, about the three decades she’d spent cooking for the Harrow family, about every batch of barrel stew she’d stirred, about the children she’d watched get sick, about the old woman who’d never recovered. “How much you need?” she asked.

Jedediah smiled for the first time since arriving. It wasn’t a happy smile. It was something sharper. “Enough to fill his belly the way he’s filled ours.”

Ruth nodded slowly. “I’ll need time.”

“I got time,” Jedediah said. “Been counting three years already. I can count a little longer.”

He left the kitchen as quietly as he’d come. Ruth stood there a long moment, looking at the barrel, thinking about what she had just agreed to. Then she got to work.

The next morning, when Ruth prepared the barrel, she set aside the worst of the worst—the meat that was clearly over the line, the corn that had gone entirely fuzzy, the vegetables that had turned to dark mush. Instead of adding them to the day’s stew, she placed them in a sealed clay pot hidden beneath a loose kitchen floorboard. Every day she added a little more—a handful here, a scoop there. Never enough to change the barrel’s usual texture, never enough to raise suspicion. Just the absolute bottom scraps, saved and stored in the dark.

The pot filled slowly. The smell became almost unbearable when she opened it. Ruth had to tie cloth over her face whenever she lifted the lid. The mixture inside was no longer just spoiled; it was dangerous in a way anyone’s nose could recognize.

“This could kill a man,” she whispered one morning, staring into the pot.

That was exactly the point.

Weeks passed, then months. Ruth continued her hidden task. Jedediah never asked about it, never mentioned it again. He simply worked in the fields, ate from the barrel, and waited. Others in the quarters noticed something different about him. He had always been quiet, but now he carried the stillness of someone with a plan.

“That big man ain’t right,” one worker said. “He look at Mister Silas like he’s seeing something I can’t.”

“Leave him alone,” another replied. “Man that size got his own thoughts.”

Cotton noticed too. He watched Jedediah carefully now, looking for signs of trouble. But there were none. Jedediah was the model worker—obedient, strong, steady. That worried Cotton more than open defiance would have.

“Something about that big one doesn’t sit right with me,” he told Silas one afternoon.

“He’s the best worker I have,” Silas replied, not looking up from his ledger. “Picks more than anyone. Never complains, never causes trouble.”

“That’s what bothers me. Man that strong, that quiet—it ain’t natural.”

Silas finally glanced up. “You want me to sell my best hand because he’s good at his job?”

Cotton didn’t answer. He knew how it sounded. But instincts honed over twenty years on different plantations told him something under the surface was wrong.

In the house, Martha Harrow noticed the tension as well. The house staff moved differently now—quieter, more deliberate. They avoided unnecessary talking. She asked Ruth one morning, “Is something wrong in the quarters?”

Ruth kept her eyes on the pot she was stirring for the owner’s lunch. “No, ma’am. Same as always.”

“You’re not telling the truth.”

Ruth’s hand paused for just a heartbeat. She was too old to fully hide her feelings. “Things been the same too long,” she said softly. “Sometimes when things stay the same too long, they got to change. That’s just how the world is, ma’am.”

Martha stared at the older woman’s back. “What kind of change?”

“Can’t say, ma’am. Don’t know myself. Just feel it coming like rain.”

Martha wanted to press, but she heard her husband’s footsteps in the hallway. She left the kitchen quickly, not wanting him to overhear. Still, Ruth’s words stayed with her. Things been the same too long. They got to change. She found herself looking out windows more often, watching the quarters, watching the fields, watching Silas stride the land with his usual certainty—and wondering if that certainty was about to cost him more than he imagined.

The pot beneath the kitchen floor was nearly full now. Three months of gathering the worst of the worst. Ruth had added more than scraps—stale fat, used grease gone solid and sharp-smelling, odds and ends that had no business anywhere near a table. Even sealed, the odor seeped up. Ruth burned extra wood in the stove to cover it, blaming the smell on a dead rat in the walls. The others believed her because they wanted to—because the alternative required asking questions best left unspoken.

One evening, Jedediah came back to the kitchen. Ruth was alone, preparing the owner’s dinner. His shadow filled the doorway. She didn’t turn around.

“It’s ready,” she said.

Jedediah nodded. “How much?”

“Near five pounds of the worst mess I ever saw. Enough to lay a horse flat.”

“Good.”

“When?” Ruth asked.

“Soon,” Jedediah said. “I’m waiting for the right moment—when he’s alone, when he comes to us instead of us going to him. He never comes to the quarters. He will. Men like him always do, sooner or later. They get angry about something small. They need to remind everyone who’s in charge. They come looking for someone to punish.”

Ruth thought about that. About five years of Silas Harrow’s decisions. About the barrel. About the children and the old woman. “What happens after?” she asked. “After you do this thing, they’ll know it came from here. They’ll punish everyone.”

“Maybe,” Jedediah agreed. “Or maybe they’ll think he ate something from his own table. Maybe they’ll say his heart gave out. Maybe they’ll never be sure. And if they do know,” he paused, “I’ll make sure they know it was me. Not you. Not anyone else. Just me.”

“They’ll hang you,” Ruth said quietly.

“Maybe,” he answered. “But I’ll go knowing he tasted what he gave us. Knowing, for once, he felt what we’ve felt. That’s worth something.”

Ruth wiped her hands on her apron. She thought of her grandchildren in the quarters—three little ones who ate from that barrel every day. “They deserve better than what he gives them,” she said.

“Yes.”

“Then do it right,” she whispered. “Make sure it counts.”

Jedediah smiled that same unsettling smile. “I will.”

He left. Ruth stood alone, staring at the floor where the clay pot rested beneath her feet. There was no turning back now. Whatever came next, she was part of it. She went back to preparing the owner’s dinner—roasted chicken with herbs, fresh vegetables, soft bread, wine from France. As she worked, she thought about justice, about what it meant, about whether making a cruel man live by his own rules was justice or simply revenge. Maybe, she decided, sometimes those two were the same.

The moment Jedediah had been waiting for came three weeks later.

A thin young man named Thomas was carrying a bucket of barrel stew to share with his family. Months of poor food had left him weak. His hands shook as he walked. The bucket was heavy. He stumbled on a stone. The bucket tipped. A portion of the thick mixture splashed onto the packed earth outside the cabin.

Thomas stared at the puddle, horrified. That was food. However poor, however hard on the stomach, wasting it was forbidden. Someone saw. Someone told Cotton. Cotton told Silas.

Silas was in his study with his ledgers when Cotton reported the spill. Something inside him snapped. All his worry about money, about control, about keeping things tight, narrowed into anger.

“Wasted food,” he shouted. “That mess costs money. Do these people think I run a charity?”

“It was an accident, sir. The boy’s weak from—”

“I don’t care if it was an accident. He needs to learn. They all do.”

Silas stood, grabbed his whip from the wall.

“I’ll handle it,” Cotton said quickly. “No need for you—”

“No. I’ll do it. I want them to see me. I want them to remember who runs this place.”

Cotton tried again to calm him, but Silas was already out the door. The overseer had seen this mood before. Once Silas got like this, reason had little effect.

Silas walked across the yard toward the quarters. It was early evening. The sun was dropping. Most of the field workers had returned to their cabins. They saw him coming, saw the leather in his hand, and slipped quickly inside. Cotton followed at a distance, a knot forming in his gut. The settlement felt too quiet. Usually, when the owner came down angry, there were already sounds—crying, pleading. Tonight, there was only a heavy silence.

Silas reached the largest cabin, where Thomas’s family stayed. He didn’t knock. He pushed the door open and stepped inside.

The room was dim. A single candle flickered in one corner. Several people were there—Thomas, his mother, two other families. And standing in the shadows at the back was Jedediah.

Silas pointed his whip at Thomas. “You spilled the food.”

Thomas nodded, trembling. “Yes, sir. I slipped. I didn’t mean—”

“Do you know what that food costs me? Do you have any idea how much money you just threw in the dirt?”

“I’m sorry, sir. I—”

“Sorry doesn’t fix waste.” Silas raised his arm. “Everyone here needs to learn.”

Before the whip could fall, a low voice came from the back of the room.

“No.”

Silas turned. Jedediah stepped forward into the candlelight. The giant of a man, towering over everyone, shoulders nearly brushing the rafters. For the first time in five years, Silas felt something unfamiliar in his own cabin on his own land: fear.

“Get back,” Silas ordered, but his voice was not as steady as usual.

Jedediah didn’t move back. He took another step forward. The others moved aside to give him space. The little room suddenly felt smaller.

“I said, get back.” Silas lifted the whip toward Jedediah now.

Jedediah moved faster than a man his size should have. His hand shot out and caught Silas’s wrist in midair. The whip stopped. Silas pulled, but the arm might as well have been made of iron.

“Let go of me,” Silas demanded. “Let go right now or I’ll—”

Jedediah’s other hand rested on his shoulder, not striking, just holding him in place with an unmistakable warning of how easily that grip could become something worse.

Outside, Cotton heard the raised voices and hurried toward the door, but people from neighboring cabins stepped into his path. They didn’t threaten him. They didn’t shout. They just stood shoulder to shoulder, a quiet wall.

He reached for his gun, then hesitated. There were too many of them. One man, one pistol—it wasn’t good arithmetic. He stayed where he was, listening.

Inside, Jedediah slowly, steadily pushed Silas downward. Not with violence, but with the calm force of someone moving a piece of furniture. Silas found himself sitting on the packed earth, expensive clothes gathering dust, the feeling of command slipping through his fingers like sand.

“What are you doing?” he said, his voice edging higher. “Do you know what they’ll do to you for this?”

Jedediah did not answer. His hand on Silas’s shoulder held him as firmly as if he’d been nailed in place.

Then a small girl stepped into the cabin. Her name was Naomi—Ruth’s granddaughter. Ten years old, thin from long months at the barrel. She carried a large wooden bowl. It was clearly heavy; her arms trembled as she set it down.

The smell hit Silas immediately. His face twisted.

“What is that?” he demanded.

Naomi placed the bowl in front of him. It was nearly full of thick, old stew—darker, heavier, more concentrated than anything he’d seen in the barrel. The surface had a dull sheen; bits of who-knew-what floated in it. The odor was overpowering.

Silas recognized it anyway. Barrel food. But not mixed the usual way. This was the concentrated worst of it, saved and combined.

“You can’t be serious,” Silas said, looking up at Jedediah. “You don’t think—”

Jedediah’s other hand moved to Silas’s jaw, turning his head back toward the bowl.

Ruth entered then, walking slowly. She looked at Silas with eyes that had watched him eat well for decades while others made do with scraps.

“Five,” she said quietly. “Same number of pounds you make forty-two people share every day. But tonight, it’s all for you, Mister Silas. Every bit.”

Silas tried to stand, but Jedediah’s hand kept him on the floor. “You can’t make me,” Silas said. “I’m the owner here. You’re all—” He stopped himself, perhaps realizing that the words he usually used had no power in that room. “This is madness. You’ll all pay for this.”

“Maybe,” Jedediah said. “But first, you eat.”

He picked up the wooden spoon resting in the bowl, scooped a heaping portion of the thick mixture, and held it near Silas’s mouth.

“Eat.”

Silas clamped his teeth shut and turned his head away. Even the smell made his stomach flip. The thought of swallowing it was unthinkable.

“You can eat it yourself,” Jedediah said calmly, “or I can help you. Either way, every last bit goes down.”

“This will kill me,” Silas gasped. “You’re trying to kill me.”

“No,” Ruth answered from behind him. “This is just supper. Same as we’ve had for years. If it’s good enough for us, it’s good enough for you.”

Silas looked around the room at the faces watching him—Thomas and his mother, the other families, even the children. Not one face showed pity. Outside, he could hear Cotton shouting, demanding to be let in. The voices that answered were steady and quiet. No one was opening that door.

“Please,” Silas said, hating the sound of his own pleading. “Please. I’ll change the food. I’ll buy proper supplies. I’ll—”

“Five years too late for ‘please,’” Jedediah replied.

He moved the spoon closer. Silas kept his jaw shut. Jedediah sighed, pinched Silas’s nose lightly between two massive fingers, and waited. Denied air, Silas held out for a few seconds. Then his chest burned. His lungs screamed. Instinct overruled pride. His mouth opened to gasp—

The spoon slid in.

The taste hit like a blow. Sour, rancid, heavy. The texture was thick and wrong. His body tried to reject it immediately. He gagged, trying to spit it out, but Jedediah’s hand covered his mouth just long enough.

“Swallow,” Jedediah said.

Silas’s throat worked. The mixture slid down. When Jedediah’s hand lifted, Silas coughed and struggled, but nothing came back up.

“That’s one,” Jedediah said. “You’ve got a lot more to match what you’ve given.”

Another spoonful. Another battle between instinct and the hand on his shoulder. Somewhere around the tenth, tears started down Silas’s face—not from pain, but from the humiliation of being held on the floor of a cabin he’d barely noticed before, made to eat what he’d always considered beneath him.

“Please,” he whispered. “I’ll do anything.”

“Anything except live by your own rules,” Jedediah said. “Interesting.”

The bowl was half-empty now. Silas’s stomach felt like it was on fire. His body was clearly reacting badly. He was sweating, breathing hard.

“I can’t,” he said hoarsely. “I can’t take another bite.”

Jedediah looked at the bowl, then at Silas, then set down the spoon.

“Then drink,” he said.

He lifted the bowl, pressed it to Silas’s lips, and tipped. The heavy mixture poured in a slow, unstoppable stream. Silas tried to turn away, but there was nowhere to go. He swallowed or choked. Reflex chose swallowing.

By the time the bowl was empty, his whole body was shaking. Jedediah set the bowl aside and finally lifted his hand from Silas’s shoulder. Silas tried to get up. His legs wouldn’t hold him. He crumpled back to the floor.

“What did you do to me?” he whispered.

“Fed you,” Jedediah answered. “Same as you fed us. Nothing more.”

Silas’s stomach clenched. His body fought the shock of what it had just taken in. His vision blurred. The candlelight wavered. Faces around him melted into shadows.

“I’ll have you all punished for this,” he managed. “Every last one…”

“Maybe,” Ruth said, “but you won’t be here to see it.”

Silas’s hand reached up weakly toward his throat. He opened his mouth, but whatever he tried to say came out as air. His breathing turned shallow and uneven. The room tilted. The last thing he saw clearly was Jedediah’s calm, unreadable face.

Then he went still.

The cabin was silent except for the sound of many people breathing. One man no longer did.

Jedediah looked down at the body and felt only completion. The account was settled. The count was finished.

Ruth bent carefully, two fingers at the side of Silas’s neck. She waited, then straightened.

“He’s gone,” she said.

Outside, Cotton heard the words through the thin boards. Heard the finality. “Break it down!” he shouted to the other white men who had gathered. “Now!”

They rushed forward. The people blocking the door stepped aside. There was no more need to hold the line. What was done could not be undone.

The men burst into the cabin and were met by the smell first—the lingering sourness of the bowl. They saw Silas on the floor, clothes askew, eyes open and empty. They saw the empty wooden bowl beside him. Cotton knelt, checked for breath, felt nothing. He looked up at the faces around him—calm, steady, waiting.

“What happened here?” he demanded.

“Mister Silas came to punish Thomas for spilling food,” Ruth said evenly. “He was angry, said we didn’t appreciate what we had. Said he’d show us what real hunger was.” She nodded at the bowl. “Then he saw that there, said if we thought it was so bad, he’d prove we were wrong. Said he’d eat it himself to teach us a lesson. He did. Whole thing. Then he went strange and fell. We tried to help, but…”

It was a story. Obviously a story. But it fit the scene. It matched the bowl, the smell, the owner’s temper everyone knew.

“You expect me to believe he ate that much of this… on purpose?” one of the men asked, face twisting as he looked into the remains clinging to the sides of the bowl.

“Mister Silas was a stubborn man,” Ruth said. “Stubborn men do stubborn things.”

Cotton stared at Jedediah in the corner, at Ruth, at Thomas, at Naomi, at the others. Every head nodded along with Ruth’s account. He looked back at the empty bowl, at the gray smear along its edges.

“He was done in by his own food,” he said at last.

“Food he ordered. Food he chose,” Ruth replied softly. “Terrible tragedy. But whose doing is that?”

In the weeks and months that followed, folks told different versions of what happened that night in the cabin on Harrow Plantation. Some said it was judgment. Some said it was simple consequence. Others said it was just a man finally forced to live under the rules he’d made for everyone else.

But everyone agreed on one thing: after that night, no owner in that county ever looked at a barrel of scraps the same way again.