Savannah, Georgia, 1935.

The city was still recovering from the Great Depression, its streets lined with oaks weighed down by Spanish moss and memories. The past lived quietly in the cracks of old brick sidewalks and the tired façades of fading mansions. In Yamacraw, one of Savannah’s oldest Black neighborhoods, history didn’t feel distant. It was close enough to sit with you on the porch.

And in a small, weather-worn cabin at the edge of that neighborhood, history had a name: Patience Monroe.

Patience’s cabin looked as if it had been standing since before the war. The boards were bleached by sun and rain, the tin roof marked by rust in slow, sprawling patterns. Children in Yamacraw sometimes said the house itself seemed to be watching.

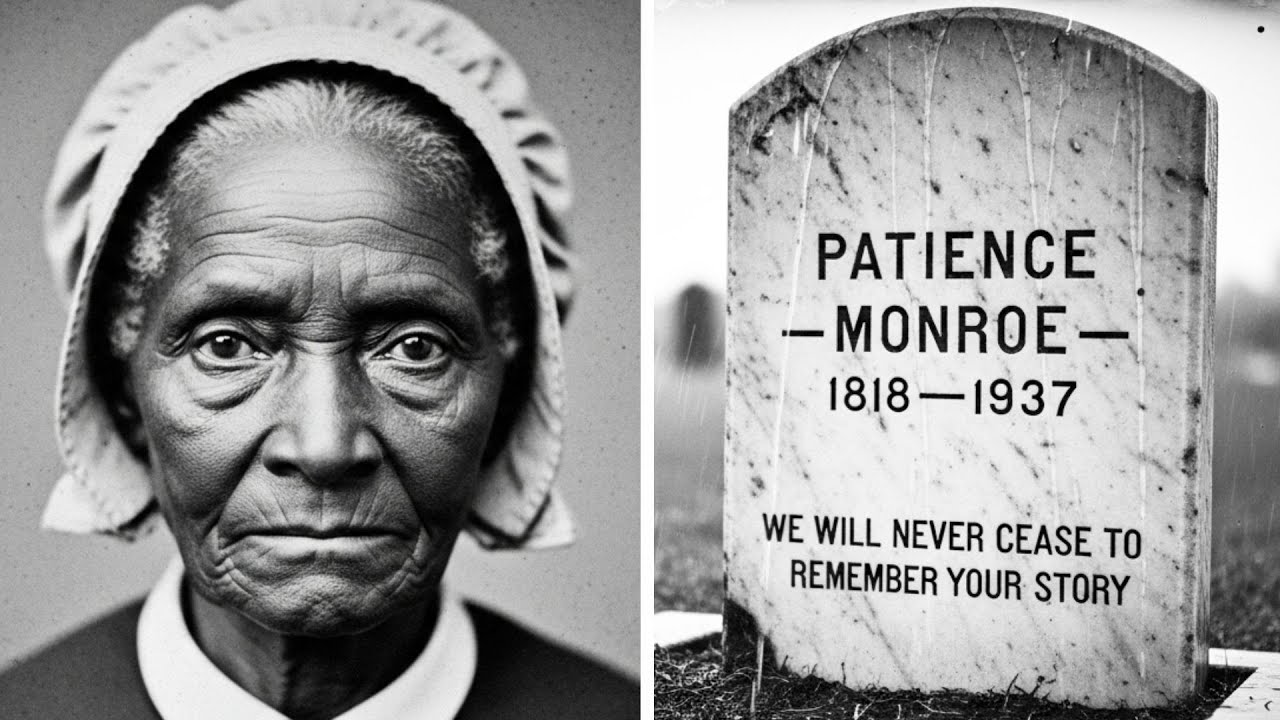

Patience looked like someone who had been shaped by many seasons. Her back was bent, her skin deeply lined, her hair a thin silver halo wrapped in a faded cloth. But it was her eyes people remembered: a clear, amber-brown that seemed to hold more than one lifetime. Children mistook her for a shadow until she moved. Adults, if they met her gaze for more than a second, often looked away—unsettled without quite knowing why.

She spoke rarely, and when she did, her voice was low and rough, forcing listeners to move closer. Her speech mixed old-fashioned English with the rhythm of Gullah and coastal Creole. To most people she was simply “Miss Patience,” a constant presence in Yamacraw that had somehow always been there.

Very few knew precisely how long “always” was.

In November 1935, Dr. Eleanor Whitmore, one of Savannah’s few female physicians, was called to the cabin. Neighbors said Miss Patience had taken a bad fall. Whitmore expected bruises, perhaps a broken bone.

She did not expect what she found.

“Her vital signs make no clinical sense,” Whitmore wrote in her diary that night. “Blood pressure unusually low yet steady. Resting pulse barely above forty-five. Body temperature slightly below normal. By ordinary standards this should indicate serious distress. Yet the patient is alert, oriented, and able to converse.”

What stayed with Whitmore even more than the medical puzzle were the traces of a life lived under constant hardship. Old injuries layered over one another: thickened skin around ankles and wrists where restraints had once been, areas of scarred tissue on her back and shoulders, evidence of bones that had broken and healed many times. Many of these marks, Whitmore estimated, had been there for decades—long enough to reach back into the era of slavery.

“Miss Patience,” she asked gently, “where were you born?”

The old woman regarded her steadily. “Blackwood Plantation,” she said at last. “Up in Georgia, before the war. My mama’s name was Rose. She came from across the water. She never let us forget it.”

As the rain tapped gently against the tin roof, Patience began to speak—not in a hurry, but in slow, careful fragments. Over many visits, those fragments became a narrative.

“I remember the smell most,” she said one evening. “Cotton has a smell, you know. Gets into everything—your hair, your clothes, your skin. When the fields were full, felt like even the air was made of it. Hot days, we’d breathe dust until our lungs burned. People would just… stop. Fall where they stood. They’d be carried aside and the rest of us told to keep working. We weren’t allowed to stop just because someone else did.”

She paused, eyes far away.

“But I remember the singing too. That’s what kept us going. Old songs our mothers brought from across the ocean, even when we didn’t know all the words anymore. Songs about rivers and walking home. We sang because silence was worse. The songs felt like holding hands when you couldn’t touch.”

Patience described being sold three times before the age of twelve. She remembered the auction block in Savannah’s Johnson Square; the way the city’s fine buildings seemed to look on and say nothing.

“The first time I stood up there,” she said, “I was nine. They looked at my teeth, my arms, my legs. Like they were checking an animal to buy. I didn’t know how to disappear, so I just stood there wishing I could stop existing. But I didn’t. I kept on living, even when I didn’t want to.”

One winter afternoon, as a storm rolled in from the river, Patience spoke of a place near Augusta—a plantation owned by a man she called Mercer.

“He liked to invent new ways to make people suffer,” she said quietly. “Punishments nobody had names for. Days in the sun with no water. Being held so you couldn’t move until your body gave out. Work pushed far beyond what a person should endure.”

She did not describe details. She didn’t need to. The weight in her voice carried enough.

“I was sure I would die there,” she continued. “But I didn’t. Every time I got close to the edge, something pulled me back. It was the same with sickness. Yellow fever came in ’32. People were here one day and gone a few days later. I burned so hot they were afraid to touch me. But I walked out of it. Cholera came later, took half the people around me. I stayed. I kept asking myself—why?”

“Perhaps you were simply very strong,” Dr. Whitmore suggested gently.

Patience shook her head. “Strength helps, but strength has limits. This felt like something else. Something that started when I was still small.”

Her voice softened when she spoke of Ayana, an older woman who lived on Blackwood when Patience was a child.

“She was from far away,” Patience said. “Some said she came on one of the last ships. She carried words nobody here understood—not the white folks, not even the other Black folks. She had ways… old ways. People went to her when doctors turned them away.”

When Patience was very young and often ill, everyone assumed she would die early. Ayana thought otherwise.

“She came to me one night,” Patience recalled. “Told me, ‘You’re not leaving yet.’ Took me by the hand and led me toward the swamp.”

Patience closed her eyes, as though watching a distant scene.

“I don’t remember everything,” she said. “It’s like part of my mind never wanted to hold it all. I remember water up to my ankles, frogs calling, air so thick it felt like we were walking through breath. She said words I didn’t know, in a language that felt older than the trees.”

She remembered Ayana taking her hand, drawing a small line on her palm, doing the same to her own and pressing them together.

“‘You will carry what others cannot,’ she told me. ‘You will live long enough to see what they dreamed of. You will remember the stories when no one else is left to tell them. This is a gift. And it is a burden.’”

Three days later, Ayana passed away in her sleep.

“After that,” Patience said, “I stopped getting sick the way other people did. Accidents that should have ended me didn’t. Illness would come, then go. And little by little, I noticed something else. When people died near me, especially when they still had stories heavy on their hearts… I started remembering things I had never lived.”

“What do you mean?” Dr. Whitmore asked. “Remembering things you never lived?”

Patience’s eyes were steady. “I remember a ship I was never on,” she said. “Dark belowdecks, wood wet with salt and fear. I remember a village near a wide river I’ve never seen, with red earth and cooking fires that smelled like palm oil. I remember a boy trying to hold on to his little sister while men pulled them apart on the beach. None of that is mine. But I carry it. As if someone laid their memories in my hands and I didn’t know how to put them down.”

Over time, she said, it didn’t stop with that one set of memories.

“Whenever someone passed near me with something heavy left unsaid, it felt like a door opening. Their last thoughts, their images, their fears—they found a place inside me. I know the final morning of a woman named Sarah, who stood between her child and a man with power over them. I know the thoughts of a man named Jacob, walking north until his feet gave out because he couldn’t accept never seeing his wife again. I know the silence of children too young to put words to what they’d lost.”

“How many lives do you think you hold?” Whitmore whispered.

“Dozens, maybe more,” Patience replied. “I stopped counting a long time ago.”

Word of Whitmore’s patient spread quietly through Savannah’s medical community. Skepticism began to crumble when other physicians examined her. Her bones bore the imprint of a body that had endured more than a century. Certain joints looked as if they’d carried weight for far longer than a human life should allow. Even her teeth showed aging at different rates.

Her recall of long-ago events was startlingly precise. When Whitmore checked details—weather patterns, crop failures, local events—the accuracy astonished her.

Professor Marcus Chen, a historian studying the region’s slavery records, soon joined the visits.

“What we rarely have are firsthand voices,” he said. “If she truly remembers, then she is a living archive.”

His files confirmed many of her claims: a bill of sale from the 1840s, movements between plantations, names that matched plantation ledgers. She remembered not only her own movements but the memories of others, preserved inside her mind.

By 1936, Patience sometimes began speaking in voices that were not her own—different ages, dialects, temperaments. During one episode, she recited a chant in a West African language. Another time, she whispered the fear of a man searching for the wife from whom he had been separated decades earlier.

Whitmore wrote, “She is not merely recalling. She is channeling. These are distinct lives surfacing through one body.”

Then a young Black journalist, Robert Harris, arrived. He wanted to document what she carried before the memories faded.

“Are you ready?” she asked him. “Because once you know, it doesn’t leave you.”

He said he was.

For three months he sat by her bed, filling notebooks with her accounts—stories of the inner world of the enslaved, the small acts of resistance, the way people sustained one another.

She spoke of the day freedom came. “I didn’t know what to do with it,” she said softly. “Forty-seven years enslaved. And suddenly, you can stand still for the first time. But I didn’t know where to go. Most of us didn’t.”

She described the fleeting hope of Reconstruction, then the return of systems designed to keep people controlled.

As the months passed, Patience weakened. She told Whitmore she could feel the memories detaching—like passengers leaving a train one by one.

“They are preparing to go,” she whispered. “All the ones I carried, they’re ready.”

Then came a period of clarity.

“It hurts,” she admitted. “Carrying so much pain for so long. But I carried their joy too. Their love. Their pride. That’s what kept me from breaking.”

“Why were you chosen?” Harris asked.

“Because someone had to keep the story,” Patience said. “Someone had to remember.”

One bright March morning, Patience asked to be taken outside. She sat beneath a live oak and sang a song in an ancient language—a song her mother had carried from the other side of the ocean.

“It’s about going home,” she said, smiling. “And I’m ready.”

A few days later, with Whitmore, Chen, Harris, and her neighbor Martha beside her, Patience took her final breath. It was quiet, almost gentle.

The coroner confirmed her astonishing age markers. Her gravestone read:

Patience Monroe

1818–1937

She remembered so we would not forget.

In the years that followed, Whitmore’s manuscript, Chen’s research, and Harris’s writings ensured that Patience’s story was not lost. Some doubted; others believed. But the records spoke for themselves.

The cabin where she lived stood for two more decades. Locals sometimes said they heard faint singing there at night. When it was demolished, the ground stayed bare for years—a quiet place where memory lingered.

Whether Patience truly lived to 119, whether Ayana’s ceremony changed something in her, whether her mind held more than one lifetime—those mysteries may never be resolved.

But her testimony remains. Her life, long beyond ordinary measure, became a vessel for countless others whose voices were nearly erased.

In the end, the greatest truth she left behind was not how long she lived, but what she chose to carry—and what she refused to let the world forget.