The Lost Journals of Saraphim’s Rest: A Georgia Plantation Mystery

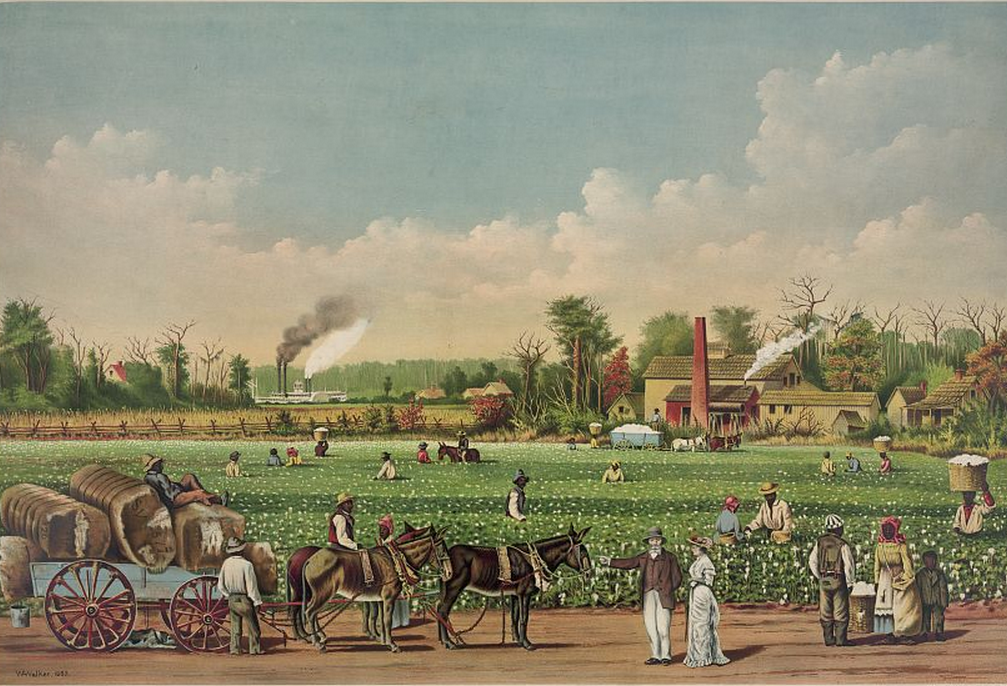

On the coastal edge of Georgia, where the marshes breathe mist and the air holds the scent of salt and pine, there lies a place locals once refused to name after dark.

Today, it’s just a ruin half-swallowed by trees and moss. But in 1841, it had another name.

Saraphim’s Rest.

A name that sounded peaceful. A place that, according to the stories, was anything but.

The Widow of Saraphim’s Rest

The story begins with a death.

One warm night in early May 1841, Augustus Vance, master of Saraphim’s Rest, was found lifeless in his bed. The county record called it sudden illness, the kind of dignified phrase that kept conversations short at church and dinner tables.

His widow, Aara Vance, stood at the center of it all.

Born Aara Devoe of Charleston, she had been married young into money and land. In public she was known as refined, educated, a little distant. In private, those closest to the family whispered that she had grown quiet over the years, as if something inside her had hardened under the weight of expectations.

She had given Augustus two daughters, but no son to extend the name. In a world obsessed with inheritance and bloodlines, that fact followed her like a shadow.

With Augustus gone, Saraphim’s Rest passed to her care in everything but legal title. For the first time in her life, Aara was not simply a wife or ornament of a household. She was, in practice, in charge.

And the plantation began to change.

A House That Stopped Singing

Those who lived and worked on the land—most of them enslaved people with no say over their own lives—felt the shift first. The easy sounds of daily routine faded. Laughter became rare. The big house, once a place of social visits and formal dinners, grew quieter, its windows shuttered more often, its doors closing earlier each evening.

Aara dismissed the overseer and began issuing every instruction herself. Work schedules shifted. Curfews tightened. New rules appeared, but no one understood the reasoning behind them. Even small habits—like when people could gather, when they could light lamps—became subjects of scrutiny.

The change was not explosive; it was steady, like a tide rising inch by inch.

What no one knew was that, inside the house, another change had taken root: a growing obsession hidden behind locked doors and heavy curtains.

Aara had always loved books. Now she began sending away for more—medical texts from Charleston, essays from Philadelphia, foreign volumes on the structure of the human body and the emerging science of “vital force.” A chest in her sitting room held notebooks and phials, tightly sealed and faintly scented with herbs and something harder to name.

She was not simply grieving. She was studying.

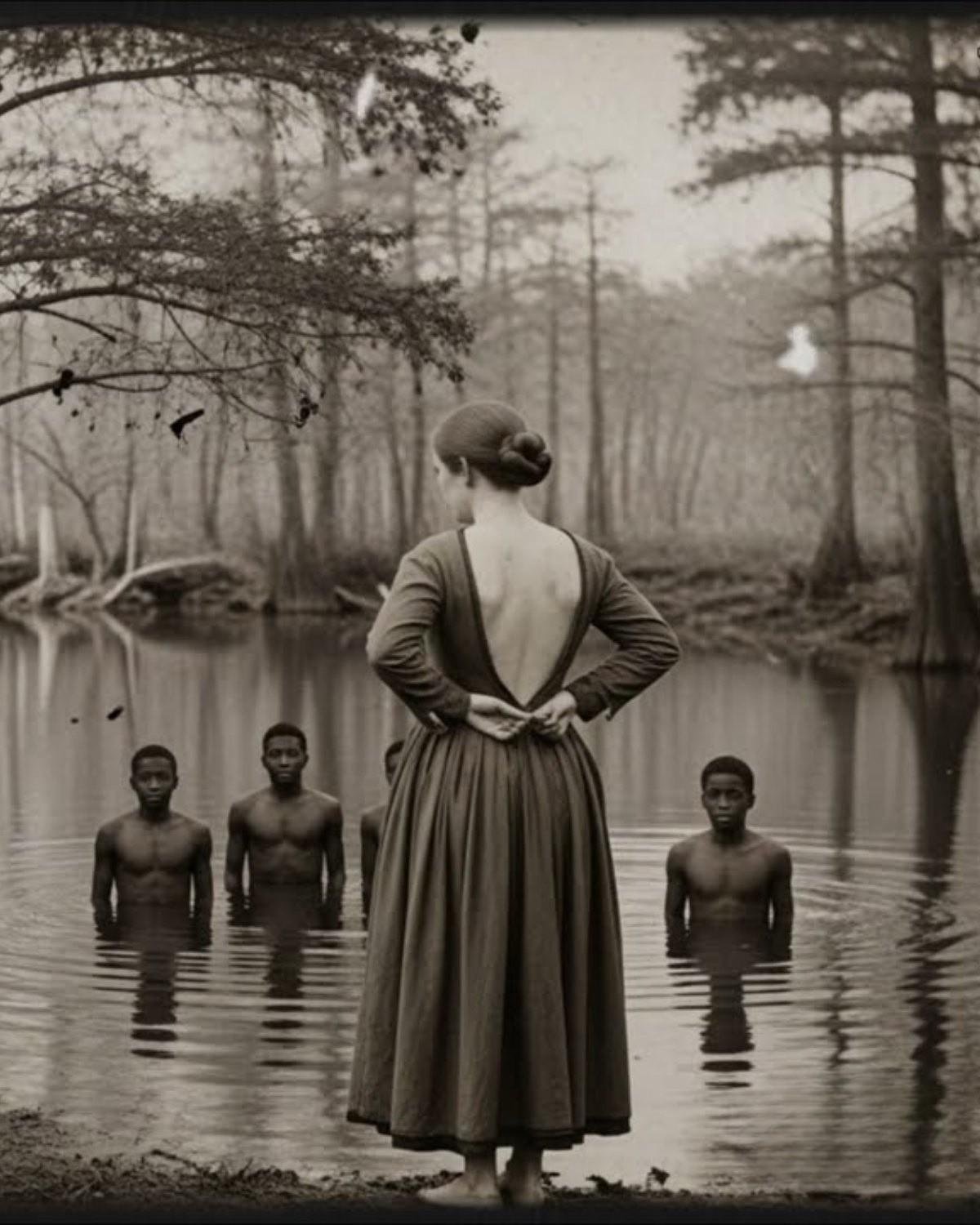

Observations in the Night

In the months after Augustus’s death, several men working close to the house were quietly summoned inside after dark—not for punishment, not for discipline, but for reasons no one could quite explain.

They were told to sit, to lie still, to rest under the watchful eye of the mistress while she took careful notes. She asked them questions about how they slept, what they dreamed, when they felt strong or weak, how the weather affected their energy. Sometimes she measured their pulse. Sometimes she simply watched their breathing.

By morning, they would be sent back to their cabins with no marks on their skin, but a lingering unease in their minds. They struggled to describe it. They only said that being in that room with her made them feel as though they were being weighed, counted, and recorded, more as specimens than as people.

Over time, a pattern emerged: those who spent the most nights under her observation began to look tired. They moved more slowly, laughed less, and stared off into the distance as if part of themselves had wandered away.

Among the enslaved community, a name took root for what was happening.

They called it “the draining.”

The Brother Who Would Not Look Away

News travels, even between places that pretend not to see each other.

By late summer, muted rumors of strange routines at Saraphim’s Rest reached Savannah, where Aara’s younger brother, Julian Devoe, lived and worked. He heard about a plantation where the songs had stopped and where the mistress kept to herself with stacks of unfamiliar books.

Julian had always admired his sister’s intelligence and will. The idea that she might be at the center of such stories disturbed him enough to act. He traveled south, following the long, shaded road through arches of oak trees until Saraphim’s Rest emerged ahead, its columns pale against the dark green of the landscape.

Aara greeted him on the veranda with perfect manners. To him, she seemed unchanged: elegantly composed, her hair smoothed, her dress immaculate. Yet something in her gaze felt sharper, as if she had learned to look through people rather than at them.

For several days, she played the role expected of her. She spoke of crops, of finances, of grief. She explained the quiet on the estate as discipline, the new schedules as “necessary order.” Every question Julian asked received an answer that sounded reasonable on the surface.

And yet, walking the grounds at dawn, he could not ignore what he saw.

Men who used to move with easy strength now worked like sleepwalkers. A house servant named Leo, whom Julian remembered as quick and bright-eyed, now seemed strangely subdued, as if carrying a weight he could not name. Conversations fell silent when Julian approached, not out of disrespect, but out of fear that spilled truth might cost them more than they could afford.

The trouble was not loud, not theatrical. It was subtle. That made it more frightening.

The Journal in the Floorboard

Julian might have left, unsettled but uncertain, if not for a chance conversation with an older woman named Hettie, known among the enslaved as a healer and midwife. One evening, as he stood near the stables pretending to admire a horse, she approached him quietly.

“Sir,” she said, keeping her eyes low, “this house is watching us even when we sleep. If you see something, don’t look away.”

It was all she dared say. But it was enough.

The next afternoon, while Aara worked in her downstairs study, Julian slipped upstairs, heart pounding. He moved through her chambers quickly, searching for anything that could explain what she was doing. At first he found only what anyone might expect: ledgers, letters, a locked cabinet of medicines.

Then he noticed one floorboard, slightly shorter than the rest near the hearth.

With his penknife, he pried it up. Beneath it lay a narrow compartment, lined with worn silk. Inside was a slim, leather-bound book.

A journal.

He opened it just long enough to confirm his fear. Neatly written lines marched across the pages: dates, initials, notes on breathing and heart rate, phrases like “subject appears subdued” and “sleep diminished after repeated observation.”

There were no gruesome details, no explicit harm described—only cold, clinical language applied to people Julian knew by name.

He slipped the journal into his coat. The decision took less than a second. Somehow, it felt like betrayal and rescue at once.

The Law Meets the House

From that moment, events moved quickly.

Julian fled to Brunswick in the middle of the night, arriving at the magistrate’s door drenched and shaking, journal in hand. Magistrate Elias Thorne was a cautious man, not easily swayed by rumor, but the sight of a plantation mistress’s private notebook describing those under her authority as “subjects” and “vessels” left him shaken.

Within hours, a small group rode back toward Saraphim’s Rest: the sheriff, two deputies, Dr. Finch—who had attended Augustus Vance in life—and Julian, clutching the journal as if it might vanish.

They arrived to find the front gate chained, the main doors barred. The sheriff read the writ that allowed entry to inspect the welfare of those living on the estate. There was a long pause, a moment when it seemed the house itself held its breath.

Then the gates opened.

Inside, the grand rooms of Saraphim’s Rest appeared orderly and still, as if waiting for guests. But behind one heavy door on the ground floor, they found what they had come to stop: Leo, pale and frightened, lying on a narrow cot, and Aara seated beside him with a notebook open and a glass vial on the table.

There was no visible harm, no spectacle. Only intent.

She looked up, more annoyed than alarmed.

“You are interrupting important work,” she said quietly.

To her, it was research. To everyone else in that room, it was a line that could not be crossed.

Leo was taken from the house. Aara was removed under court order to a private institution, her mental state deemed too dangerous for her to remain in charge of others. The journal was placed into the county archive, where it would lie undisturbed for decades.

Saraphim’s Rest, without its mistress, began to unravel.

The Ruins and the Return

Years passed. The plantation changed hands, then burned under unclear circumstances. Nature moved in where people moved out. By the time the 20th century arrived, the once-grand house was reduced to brick outlines and broken steps, its story half-remembered in local whispers of “the woman who measured people like clocks.”

In the 1930s, a federal survey team recorded the ruins and salvaged a few objects, including an old brass key stamped with two initials: A.V. They noted the site, then moved on. The key went into a box, then a drawer, then a shelf.

It waited there for nearly a century.

In 2019, a university team returned to the area to document lost plantation sites and the lives of the people who had labored on them. At Saraphim’s Rest, they found the buried remains of a small iron chest. Inside, wrapped in decaying cloth, was another journal.

The handwriting matched the first.

In this second volume, written during Aara’s years in the institution, there were no more “subjects.” Only reflections—on control, on fear, on the temptation to use knowledge without restraint. The tone was not remorseful, but it was restless, as if she were still arguing her case to a future that might finally understand her.

The researchers did not publish the pages verbatim. Instead, they used them to frame a larger story: not only about one woman, but about an entire system that allowed some people to treat others as material to be measured, directed, and managed.

Today, a small marker stands near the marsh where Saraphim’s Rest once rose. It does not carry the Vance name. It does not name Aara. Instead, it honors those whose lives were lived in the shadow of a house that valued control more than compassion.

Locals sometimes say the soil remembers.

Saraphim’s Rest is gone, but its lessons remain—quiet, patient, and waiting for anyone willing to read them.