The Portrait That Wouldn’t Let Go: The Tragic Story Behind a Victorian Photograph

London, 1887.

In a modest townhouse on Waverly Crescent, a portrait hung above the mantelpiece for generations — a mother in fine silk, her two daughters at her side, their faces serene, their posture immaculate. Visitors admired its composition, the subtle lighting, the air of quiet grace. Few lingered long enough to notice what the photograph truly was.

For decades, it seemed a beautiful keepsake of Victorian gentility. But beneath the glass, hidden in plain sight, was one of the era’s most haunting relics — a reminder of how grief once intertwined with art.

A Visit to Fleet Street

It was a cold February afternoon when Mrs. Eleanor Whitcombe stepped into a portrait studio on Fleet Street. The air smelled of varnish and chemicals; the photographer adjusted his brass lens while muttering about light and exposure.

She carried two small dresses folded neatly in her arms — one lilac, one cream. Behind her, an attendant followed, holding something swaddled in a thick woolen blanket.

“Are you certain, madam?” the photographer asked quietly.

“I am,” Eleanor replied. Her voice was calm, her hands steady inside her gloves. “They deserve to be remembered as they were — together.”

The man nodded. He had taken portraits like this before. In 19th-century London, where fever and influenza claimed lives with cruel frequency, mourning photography had become a somber custom. Families would commission final portraits of loved ones — particularly children — arranging them as if still alive, eyes open, surrounded by those they had left behind.

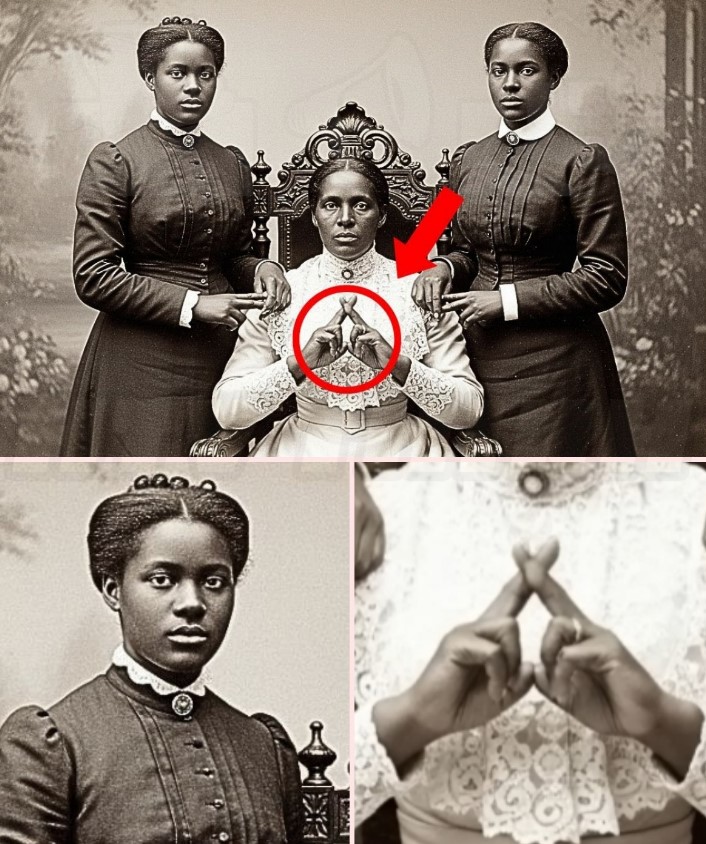

The Photograph

When the plate was developed, the result was deceptively beautiful. Eleanor sat upright, her expression dignified, the lace of her gown glowing softly in the light. The two little girls beside her — their curls brushed, ribbons perfectly tied — seemed merely tired, as if resting after play.

But the longer one looked, the more unease settled in.

The girls’ skin was too pale, their eyelids faintly darkened, their lips rigid. Their small hands, folded delicately in their laps, appeared stiff. The younger child’s fingers rested atop her sister’s — pale, motionless, waxen.

The photographer, skilled in his melancholy craft, had done what he could. He tilted their heads, painted faint blush onto their cheeks, and added light to their eyes in the final print. The illusion was nearly perfect.

When Eleanor received the finished photograph, she smiled. For one fleeting instant, she could pretend that her daughters were still with her.

A Family Secret Preserved

For years, the portrait hung in the Whitcombe home. Visitors commented on its beauty, unaware that two of the three faces had long been buried in Highgate Cemetery. To the family, it was not a secret to be discussed but a sacred memorial — a way of keeping love visible.

When Eleanor passed away in 1912, the portrait went to her nephew, who had it cleaned and reframed. It remained a decorative heirloom until, almost a century later, it resurfaced at an estate sale in 1989.

A collector of Victorian memorabilia bought it, struck by its uncanny stillness. During restoration, a conservator noticed faint brushstrokes around the eyes — the telltale signs of retouching common in postmortem photography. Under magnification, the hands showed minute traces of stiffening — flesh photographed after life had fled.

The Ledger Entry

Further research uncovered the original photographer’s ledger in an archive of London studios. Next to the entry for “Mrs. Whitcombe and daughters,” a short notation appeared in delicate script:

“Special request. Mother insisted both appear awake. Exposure difficult due to condition.”

No further comment was recorded.

The Era of Mourning Photography

To modern sensibilities, the practice can seem macabre. Yet for Victorians, it was an act of mercy — a final, tangible link to those lost too soon. Death, ever-present in an age of epidemics, was woven into daily life. The camera offered solace, freezing the illusion of continuity between the living and the dead.

In that world, photography was not merely an art form. It was memory made visible.

As one historian of the period, Dr. Harriet Lowenfeld, notes:

“For the Victorians, mourning photography was not morbid — it was love refusing silence. These images are less about death than defiance, a refusal to let go.”

A Mother’s Expression

What draws viewers most to the Whitcombe portrait, now held in a museum archive, is not the children’s stillness but the mother’s face. She is composed, yet her eyes seem distant — as though suspended between duty and despair. Her gloved hand rests protectively on her youngest daughter’s shoulder, but her fingers tremble slightly, betraying the truth the photograph was meant to conceal.

It is not merely a likeness. It is a farewell disguised as a moment of life.

Rediscovery and Reflection

Today, the photograph resides in controlled storage, exhibited rarely to prevent fading. When it is displayed, visitors often approach it without context — admiring the craftsmanship, the delicacy of tone, the grace of the subjects.

Then, inevitably, their gaze shifts downward, toward the hands. And realization dawns.

What seemed at first a tender portrait of Victorian refinement becomes something altogether different — a record of loss, devotion, and the strange ways humans resist impermanence.

The Whitcombe portrait has become a cornerstone in exhibitions exploring Victorian mourning culture, appearing in collections alongside jewelry made from hair, letters sealed with black wax, and memorial lockets containing photographs of the departed.

Each object tells the same story in a different voice: love that refused to fade.

The Letter

When archivists examined the belongings found with the photograph, they discovered a small, yellowed note — a letter written by Eleanor herself sometime after 1887. Its ink had faded, but one line remained clear:

“The dead do not vanish. They remain in the photographs, waiting for us to remember.”

It was signed simply, E.W.

Her words encapsulate both the tenderness and tragedy of an age that sought to make peace with mortality through art. The portrait, long misunderstood, now serves as a reminder that photography — in its earliest form — was as much about remembrance as representation.

Love Beyond the Frame

Viewed through modern eyes, the Whitcombe portrait is unsettling, yet profoundly moving. It forces us to confront the delicate boundary between memory and mourning, between art and grief.

To Eleanor, it was never an artifact of death. It was proof that love could be captured — if not in heartbeat, then in light.

And so the mother sits eternally beside her daughters, bound not by time but by tenderness, their hands forever joined in that fragile illusion of life.

Sources

- Victoria & Albert Museum – Mourning and Memory in Victorian Photography

- The Guardian – “How the Victorians Photographed the Dead” (2023)

- [British Library Archives – Early Photographic Practices in 19th-Century London]

- [National Portrait Gallery – Victorian Postmortem Portraiture Collection Notes]

- [Museum of London – Social History of Grief and Commemoration]