For thousands of years, human remains have carried silent stories of life, struggle, and loss. One of the most extraordinary examples is the Detmold Child, a Peruvian mummy dating back 6,500 years. Predating Tutankhamun by over three millennia, this tiny individual has become a symbol of how modern science can illuminate the past — while also sparking ethical debates about how we engage with ancient remains.

Through advanced imaging and analysis, researchers have pieced together not only the medical conditions that shaped this child’s short life but also broader questions about health, culture, and respect for the dead.

The Discovery of the Detmold Child

The Detmold Child is considered one of the oldest preserved mummies in the world. Unlike Egyptian mummies deliberately embalmed for ritual purposes, this infant was naturally preserved in the dry climate of ancient Peru.

Discovered in the Andean region and later acquired by the Lippe State Museum in Germany, the mummy quickly gained attention from historians, archaeologists, and medical experts. What made the case extraordinary was not just the child’s age but the remarkable preservation, which allowed modern science to study it in ways unimaginable even a generation ago.

Using Modern Science to Study Ancient Remains

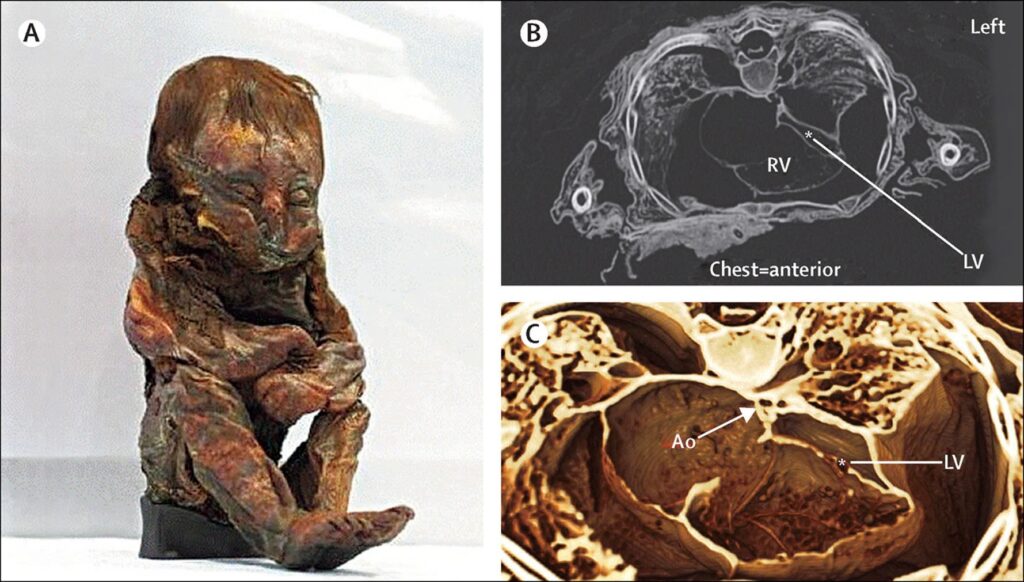

Researchers from the North Rhine Westphalia Heart and Diabetes Centre (HDZ NRW), working in partnership with the Lippe State Museum, applied high-resolution CT scanning to the mummy. This non-invasive technology provided an unprecedented look into the child’s internal structure without disturbing the remains.

The scans revealed details about bone development, organ shape, and evidence of disease. This level of insight has transformed mummy studies, replacing older methods that often required direct dissection.

A Rare Congenital Heart Condition

The most significant discovery was evidence of hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS). This rare congenital defect occurs when the left side of the heart — which pumps oxygen-rich blood to the body — fails to develop fully.

Today, HLHS is usually diagnosed in infancy and requires complex surgical interventions for survival. But 6,500 years ago, there was no medical knowledge or treatment available. For the Detmold Child, the condition meant life would always have been fragile and short.

This diagnosis highlights both the limitations of ancient medicine and the resilience of human survival against natural odds. The child lived for 8 to 10 months, an impressive span considering the severity of the condition.

Multiple Health Struggles

The CT scans also revealed other health challenges that likely contributed to the child’s early death.

-

Vitamin D deficiency: Evidence of rickets suggested the child may not have received enough sunlight exposure or sufficient nutrients in early life.

-

Turricephaly: The skull shape showed signs of abnormal development, creating a conical appearance. This condition is often linked to genetic or environmental factors.

-

Respiratory illness: Signs of infection, possibly pneumonia or tuberculosis, indicated the child was battling a serious lung condition at the time of death.

The combination of congenital heart disease, nutritional deficiency, and infection paints a tragic but scientifically rich picture of life in ancient Peru.

What This Tells Us About Ancient Peru

Although the Detmold Child cannot speak, the mummy provides powerful insights into early Andean life.

-

Healthcare limitations: Without modern medicine, many infants with congenital disorders did not survive beyond their first year.

-

Nutritional environment: Vitamin deficiencies suggest that even in fertile regions, diet and environmental exposure could be inconsistent.

-

Community resilience: The fact that the child lived as long as it did indicates care and attention from caregivers, reminding us of the enduring human instinct to nurture and protect.

From Exhibition to Ethical Debate

The Detmold Child gained international fame when it toured the United States as part of the Mummies of the World exhibition, which showcased more than 150 mummies from cultures across the globe. Visitors marveled at the opportunity to see such well-preserved remains up close.

Yet the display also sparked ethical debates. Should human remains, particularly those of children, be exhibited in public museums? Does the educational value outweigh the potential for sensationalism?

Video

-

Education: Exhibitions allow the public to learn about ancient civilizations in direct and impactful ways.

-

Scientific awareness: They highlight advances in research methods and encourage appreciation of medical science.

-

Cultural connection: Seeing human remains can foster empathy and a sense of continuity with the past.

Arguments Against Display

-

Respect for the dead: Some believe human remains should not be treated as artifacts but rather buried or memorialized.

-

Cultural sensitivity: Descendant communities may find displays inappropriate or offensive.

-

Commercialization concerns: Critics argue that ticketed exhibitions risk reducing human lives to entertainment.

The debate remains unresolved, but it underscores the tension between curiosity and respect when it comes to ancient remains.

Lessons from the Detmold Child

The Detmold Child has become more than a scientific case study. It represents the intersection of medical discovery, cultural history, and ethical responsibility.

-

For medicine, it demonstrates how congenital conditions existed long before modern records and how science can diagnose them centuries later.

-

For history, it provides a rare window into prehistoric Peru, revealing not only diet and health but also the universality of human struggle.

-

For society, it prompts reflection on how we honor the dead while still learning from them.

FAQs: Understanding Ancient Mummies and Health

How old is the Detmold Child?

The mummy is approximately 6,500 years old, making it one of the oldest known preserved mummies in the world.

What caused the child’s death?

A combination of hypoplastic left heart syndrome, vitamin D deficiency, and respiratory infection most likely contributed to the early death at 8–10 months old.

Is the Detmold Child unique?

Yes. While many mummies have been studied worldwide, very few infant mummies from such an early period exist with this level of preservation.

Why is there debate over displaying it?

Some argue that displaying human remains is educational, while others feel it disrespects the dead and their descendants.

Where is the Detmold Child now?

After touring in the U.S., it has been returned to the Lippe State Museum in Detmold, Germany, where it is currently housed.

Conclusion

The Detmold Child’s story is one of fragility, discovery, and reflection. This 6,500-year-old Peruvian mummy has taught us about ancient diseases, nutritional struggles, and the limits of prehistoric medicine. At the same time, it has forced us to confront deeper questions about ethics, respect, and the role of museums in educating the public.

By examining the Detmold Child with compassion and care, we not only honor the life of a long-lost infant but also deepen our understanding of what it means to be human — across time, culture, and history.