In the summer of 2025, an international team of paleoanthropologists announced a discovery that reshapes our understanding of human evolution in Asia. At the Hualongdong site in Anhui Province, China, researchers studied dental remains dating back around 300,000 years. These teeth, preserved within a remarkably complete cranium, revealed an unexpected blend of anatomical traits—some primitive, others distinctly modern.

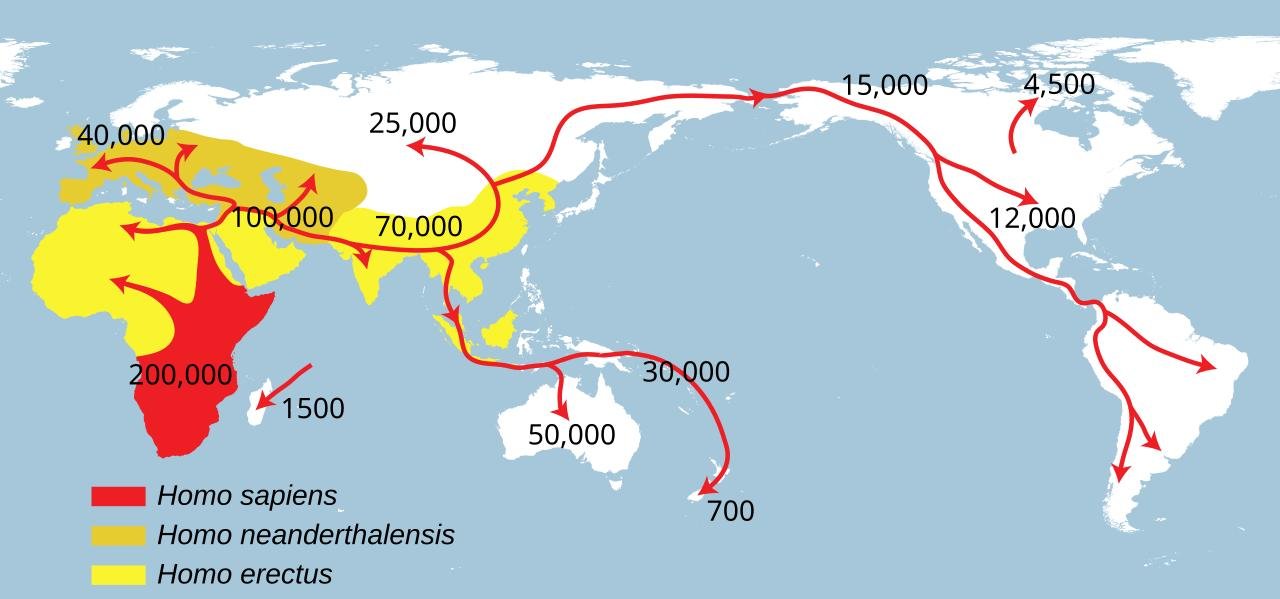

The findings, published in the Journal of Human Evolution, suggest that Asia during the Middle Pleistocene (roughly 780,000 to 125,000 years ago) was not home to a single line of human ancestors, but rather to a variety of populations experimenting with different evolutionary pathways.

The study adds to a growing body of evidence showing that human evolution was not a straightforward process. Instead, it was a complex mosaic of overlapping lineages, interbreeding, and regional adaptations.

The Discovery at Hualongdong

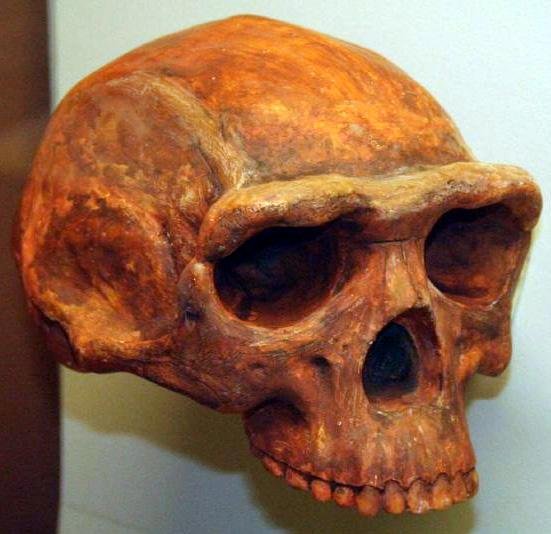

Excavations at Hualongdong began in the early 21st century, with major fossil finds occurring between 2014 and 2015. Among them was a well-preserved hominin skull, including parts of the face and jaw. Later analyses uncovered 21 dental elements, 14 of which remained embedded in the skull.

Led by Professor Wu Xiujie of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) in Beijing, and in collaboration with the Centro Nacional de Investigación sobre la Evolución Humana (CENIEH) in Spain, the research team set out to examine the dental features in detail.

Their analysis confirmed what earlier skeletal studies had hinted: the Hualongdong hominins were unlike any other known group.

A Mosaic of Traits

The dental remains displayed a fascinating combination of features:

-

Modern-like traits: Small third molars and smooth buccal (cheek-facing) surfaces, characteristics closer to modern humans (Homo sapiens).

-

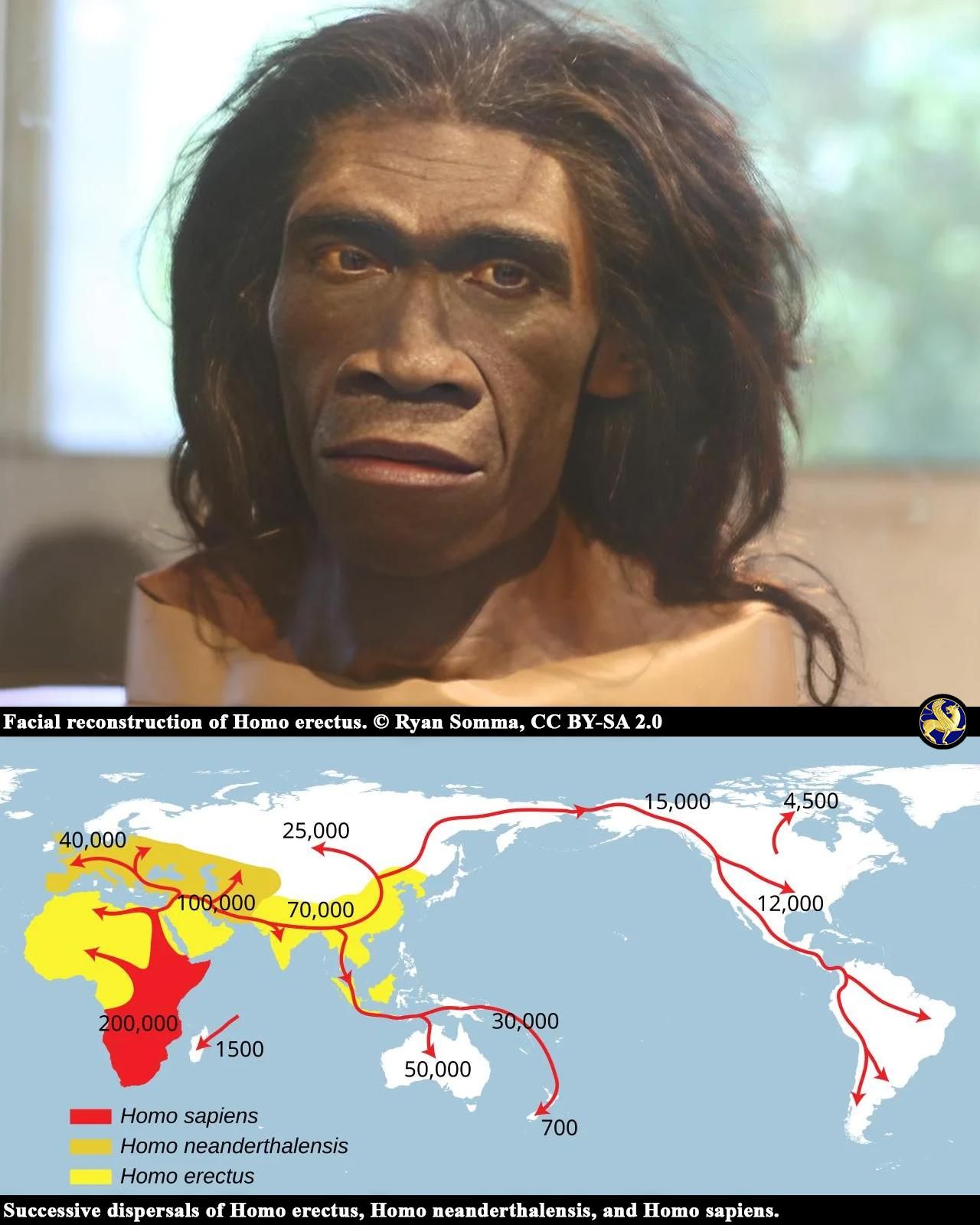

Archaic traits: Large, robust molar and premolar roots, typically associated with Homo erectus, an earlier hominin species that spread widely across Asia.

This mixture mirrors the broader skeletal evidence. The face of the Hualongdong fossils shows proportions closer to Homo sapiens, while the jaw and limbs retain a sturdier, more archaic build.

According to María Martinón-Torres, Director of CENIEH, “It’s a mosaic of primitive and derived traits never seen before—almost as if the evolutionary clock were ticking at different speeds in different parts of the body.”

Her colleague, paleobiologist José María Bermúdez de Castro, added: “The Hualongdong discovery reminds us that human evolution was neither linear nor uniform, and that Asia hosted multiple evolutionary experiments with unique anatomical outcomes.”

Distinct from Neanderthals and Denisovans

One of the most significant aspects of the Hualongdong fossils is what they lack. Unlike Neanderthal or Denisovan remains, the Hualongdong teeth show no distinct Neanderthal features—such as the characteristic large interproximal contact areas or shovel-shaped incisors.

This suggests that the Hualongdong population was not part of the Neanderthal or Denisovan lineages. Instead, they represent either:

-

A unique population of hominins in East Asia that shared ancestry with modern humans.

-

Evidence of gene flow—interbreeding between an early Homo sapiens-like population and archaic groups such as Homo erectus.

-

A distinct lineage, related to modern humans but not identical to any known species.

Implications for Human Evolution in Asia

The Hualongdong discovery adds complexity to the human evolutionary story in Asia. For decades, Homo erectus was considered the dominant species in East Asia for nearly two million years. However, recent finds suggest that Asia hosted a much greater diversity of hominins than previously recognized.

Some of the most significant discoveries include:

-

Homo luzonensis (Philippines, 2019): A small-bodied species with unique dental and skeletal traits, dating to at least 50,000 years ago.

-

Homo longi (China, 2021): A large-skulled hominin, now widely considered to be Denisovan.

-

Homo juluensis (China, 2024): Another recently proposed species based on fossil evidence, dating to around 300,000 years ago.

These discoveries suggest that during the Middle Pleistocene, Asia was an evolutionary hotspot, where multiple hominin populations coexisted, interacted, and possibly interbred.

Advanced Traits Emerging Earlier Than Expected

Despite being 300,000 years old, the Hualongdong teeth show several traits associated with later populations and even modern humans. These include:

-

Human-like occlusal outline: The chewing surfaces resemble those of Homo sapiens.

-

Advanced groove patterns: The structure of premolars shows complexity typical of Late Pleistocene hominins.

This indicates that some modern traits were already appearing in Asia long before Homo sapiens spread globally around 60,000 years ago.

Scientific Methods Behind the Analysis

The study relied on a combination of traditional comparative anatomy and advanced imaging techniques. Using 3D micro-CT scans, the researchers were able to examine the internal structures of the teeth, including root morphology and enamel thickness.

The fossils were then compared with thousands of dental samples from other hominin species across Africa, Europe, and Asia. This allowed scientists to identify the unique “mosaic” pattern of traits at Hualongdong.

Evolutionary Scenarios

The team outlined several possible explanations for the unusual traits:

-

Interbreeding Hypothesis: The population could represent a hybrid community, the result of genetic mixing between early Homo sapiens-like groups and archaic Homo erectus.

-

Unique Lineage Hypothesis: The Hualongdong hominins might belong to a separate evolutionary branch that eventually contributed to modern humans.

-

Regional Adaptation Hypothesis: Isolated populations in East Asia may have developed distinct traits through adaptation to local environments, while still retaining some archaic features.

Each hypothesis highlights the complexity of human evolution and the need for more fossil evidence from Asia.

Broader Context: The Middle Pleistocene Puzzle

The Middle Pleistocene is often described as the “black box” of human evolution. Fossil evidence is sparse, and yet it was a critical time when many distinct human lineages emerged and interacted.

Discoveries like Hualongdong, alongside Panxian Dadong and Jinniushan in China, are filling in this gap. These sites collectively suggest that Asia was not a peripheral stage but a central arena in human evolution.

Future Research Directions

The next steps for researchers include:

-

Expanding excavations at Hualongdong to search for additional skeletal remains.

-

Conducting isotopic analyses to reconstruct diet and environmental adaptation.

-

Attempting to recover ancient DNA, though preservation in East Asian climates makes this challenging.

-

Comparing Hualongdong fossils with other Middle Pleistocene finds to clarify their evolutionary position.

Why It Matters

The Hualongdong discovery underscores that human evolution was multilinear—a process of branching, mixing, and adaptation rather than a single line of progress. It challenges long-held assumptions and highlights Asia’s critical role in shaping modern humanity.

By showing that modern human traits appeared earlier in Asia than expected, the study raises important questions about where and how Homo sapiens acquired their defining characteristics. It also emphasizes the need to look beyond Africa and Europe when reconstructing our species’ global story.

Conclusion

The 300,000-year-old teeth from Hualongdong represent one of the most significant paleoanthropological discoveries of the decade. Their unusual combination of primitive and modern traits reveals a complex evolutionary landscape in East Asia, where multiple lineages of humans once coexisted and possibly interbred.

Although many questions remain unanswered—particularly regarding the precise identity of the Hualongdong population—the find provides compelling evidence that human evolution was far more diverse and interconnected than previously understood.

As more discoveries emerge from sites across China, the Philippines, and beyond, the human family tree will likely become even more intricate. But one message is clear: Asia was not a silent backdrop to evolution—it was a dynamic center of innovation, adaptation, and survival.

Sources

-

National Geographic – Hualongdong and Asian Fossil Discoveries

-

CENIEH (Centro Nacional de Investigación sobre la Evolución Humana) – Research Updates

-

IVPP (Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Beijing)