In the world of history and science, there are discoveries that inspire awe, others that spark debate, and some that straddle the curious line between myth and reality. One such case is the enigmatic Merrylin Cryptid Collection, often referred to as Merrylin’s Macabre Museum. Hidden away in the cellar of a London townhouse and rediscovered in the early 2000s, this collection of strange specimens has captivated researchers, skeptics, and storytellers alike. From skeletal remains resembling dragons and faeries to carefully preserved creatures straight out of folklore, Merrylin’s collection challenges us to reconsider the boundaries of imagination, biology, and belief. But what exactly is the truth behind this mysterious trove?

Unearthing History: The Man Behind the Mystery

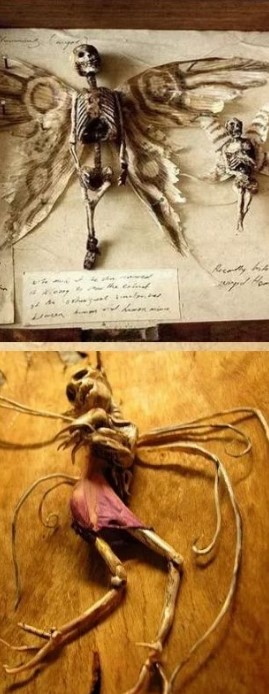

The story begins with Thomas Theodore Merrylin, an eccentric 19th-century naturalist and collector whose life remains cloaked in myth. Born in 1782, Merrylin is said to have devoted his life to the study of natural history and cryptozoology—the pursuit of animals whose existence is suggested in myths but unproven by science. By the late 1800s, Merrylin had allegedly amassed a collection so unusual that it blurred the lines between scientific curiosity and fantastical imagination. His specimens included skeletal remains that resembled mythical beings—miniature humanoid figures, winged creatures, and skeletal formations that looked like dragons or goblins from European folklore. For decades, the collection vanished into obscurity, stored in the basement of a London property. It was only in the early 21st century that the crates were rediscovered, bringing Merrylin’s work back into the public eye.

The Macabre Collection: Folklore in Physical Form

What makes the Merrylin Museum so compelling is not just the breadth of the collection, but its uncanny resemblance to creatures that have lived for centuries in human imagination. Faeries and sprites: Delicate skeletons with fine bone structures and elongated limbs, some with hints of wings, suggesting physical embodiments of European fairy tales. Dragons and serpentine forms: Tiny reptilian skeletons with elongated spines and pronounced jaws, fueling speculation about whether Merrylin was attempting to “prove” dragon myths. Chimeric creatures: Specimens that combined characteristics of multiple animals—bat-like wings with feline skulls or avian skeletons with distinctly humanoid features. For enthusiasts of folklore and fantasy, Merrylin’s cryptids offer a tangible link to stories passed down through generations. For skeptics, however, they raise questions about fabrication, artistry, and the blurred line between science and spectacle in the Victorian era.

Science, Skepticism, and Speculation

Scholars and scientists who have studied the collection remain divided. Some argue that Merrylin was an early pioneer in taxidermy artistry, creating hybrid skeletons as a way to explore evolutionary concepts or to provoke public fascination. In the 19th century, when the boundaries of natural history were still being defined, such displays would not have been unusual. Others suggest that Merrylin was part of a broader Victorian fascination with the macabre, blending pseudoscience, performance, and art. Exhibitions like P. T. Barnum’s “Feejee Mermaid” had already blurred the lines between authenticity and illusion, and Merrylin’s work may have been part of this cultural phenomenon. Yet there are still those who treat the collection as genuine evidence of unknown creatures, pointing to the meticulous construction of the skeletons and the strange consistency across dozens of specimens. While no definitive scientific proof has ever validated the creatures as real, their mystery continues to ignite debate.

The Cryptid Legacy: Why It Captivates Us

Why does Merrylin’s collection continue to fascinate us today? The answer lies in its unique ability to bridge multiple worlds. Science and mythology: The specimens suggest that myths might have some physical basis, sparking curiosity about the origins of folklore. Art and reality: Even if fabricated, the level of craftsmanship speaks to a Victorian obsession with blurring art and authenticity. Fear and wonder: The collection plays into universal human emotions—our fear of the unknown and our wonder at the possibility of hidden worlds. In a time when scientific discovery was rapidly expanding human knowledge, collections like Merrylin’s allowed people to dream about what still might be lurking in the shadows of the earth.

Merrylin’s Museum in Modern Culture

Today, the Merrylin Cryptid Collection has found a new life not only in museums but also online, where photographs and digital reconstructions circulate widely. It has inspired documentaries and YouTube explorations, where enthusiasts dissect the possibilities of Merrylin’s work. It has appeared in fantasy literature and art, as writers and illustrators reimagine the cryptids as living beings in new stories. It has also sparked debates in scientific forums, where researchers weigh the collection’s artistic value against its historical implications. The museum has become a symbol of curiosity—a place where imagination and evidence converge, where even skeptics admit to feeling a chill of wonder.

A Victorian Obsession with the Strange

To understand Merrylin’s work, it helps to place it in the broader context of Victorian society. The 19th century was an era of both scientific revolution and fascination with the bizarre. Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859) had just challenged traditional ideas about creation, while archaeological discoveries were rewriting human history. At the same time, spiritualism, séances, and exhibitions of “oddities” flourished. Audiences craved spectacles that blurred fact and fiction, eager to explore the mysterious boundaries of the natural world. Merrylin’s cryptids fit neatly into this cultural appetite—provoking questions without providing definitive answers.

The Human Element: Wonder and Belief

At its core, Merrylin’s Museum is less about whether the specimens are real and more about what they mean. They embody the human longing for mystery, for proof that legends might hold truth, and for reminders that the world is not yet fully explained. Each skeleton, whether authentic or fabricated, tells us something about the people who created, preserved, and later rediscovered it. They are artifacts not just of biology but of imagination, representing humanity’s eternal dance between skepticism and belief.

Conclusion: Where Science Meets Storytelling

Merrylin’s Macabre Museum remains one of history’s most peculiar legacies—a collection that refuses to fit neatly into categories of science or fiction. Whether one views it as an elaborate artistic project, a pseudo-scientific experiment, or an archive of genuine cryptids, it continues to capture attention because it embodies the timeless allure of the unknown. As visitors and scholars peer into the cases of winged skeletons and chimeric beings, they encounter not only questions about Merrylin’s motives but also deeper questions about themselves. Why do we crave the mysterious? Why do we long for proof that myths are real? And what does our fascination with the macabre reveal about our shared humanity? Merrylin’s Cryptid Collection does not provide easy answers. Instead, it offers something far more valuable: an invitation to wonder, to question, and to imagine.