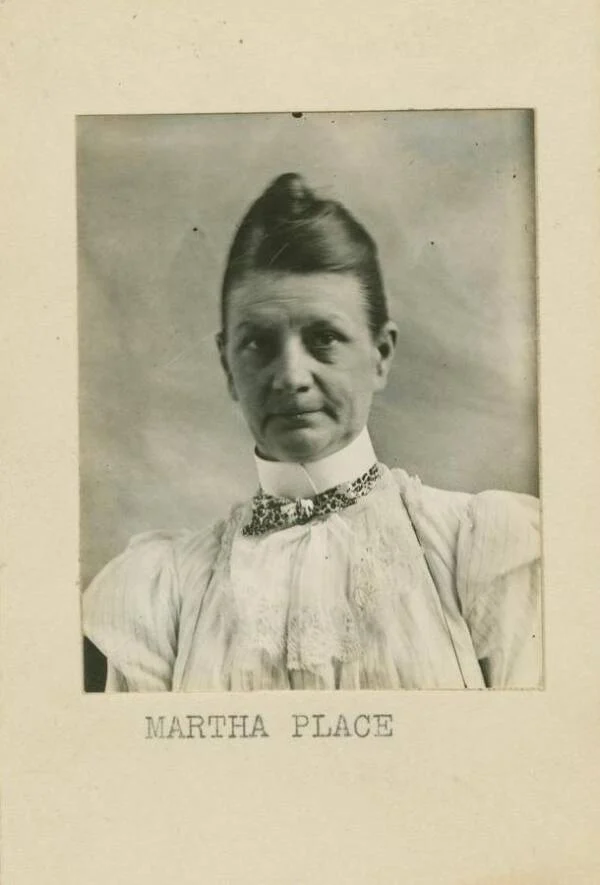

On March 20, 1899, Sing Sing Prison in New York became the stage for an event that would shape the history of American justice. Martha Garretson Place, a 49-year-old woman from Brooklyn, was executed for the death of her stepdaughter, Ida. Her case marked the first time in U.S. history that the electric chair—a relatively new and controversial invention at the time—was used on a woman. The trial, conviction, and execution of Martha Place remain significant not only for their judicial implications but also for what they reveal about society’s views on gender, justice, and punishment at the turn of the 20th century.

A Life Shaped by Hardship

Martha Garretson was born on September 18, 1849, in Millstone, New Jersey. From an early age, she endured hardships that would leave lasting marks on her life. At age 23, she suffered a head injury in a sleigh accident. Family members later testified that her personality and health seemed permanently altered afterward. Her brother noted that she “never fully recovered,” suggesting that the trauma left her struggling with both physical and emotional stability.

In the years that followed, Martha’s personal life was marked by a series of disappointments. She married, but her marriage ended in separation, and her only child was given up for adoption after her husband abandoned her and later died. Without family stability or financial security, she sought employment to support herself. Eventually, she found work as a housekeeper in Brooklyn—a position that brought her into contact with William Place, a widower raising his daughter, Ida.

Marriage and Domestic Conflict

Martha and William married, and she took on the role of stepmother to William’s teenage daughter. But domestic harmony was elusive. Reports at the time suggested that Martha harbored jealousy toward Ida, particularly as the young girl grew older and William appeared attentive to her needs. Neighbors and newspapers alike described a household tense with resentment.

The New York Times later reported during Martha’s trial that her jealousy quickly escalated into bitterness. Observers noted that she seemed increasingly insecure as Ida blossomed into adulthood. This tension created a household environment that was volatile, and eventually, it led to tragedy.

The Incident in 1898

In February 1898, tensions in the Place household erupted. Following a dispute, William left for work, leaving Martha and Ida at home. Later that day, Ida was found dead, and William was injured after a confrontation with his wife. Police quickly arrested Martha.

Newspapers seized upon the story, labeling her “The Brooklyn Murderess.” Late 19th-century journalism was known for its sensationalism, and reporters highlighted details of the crime in lurid fashion. Headlines emphasized her gender, her role as a housekeeper turned wife, and the notion of jealousy within the family. The coverage created a spectacle, ensuring that her upcoming trial would capture widespread attention.

The Trial and Public Reaction

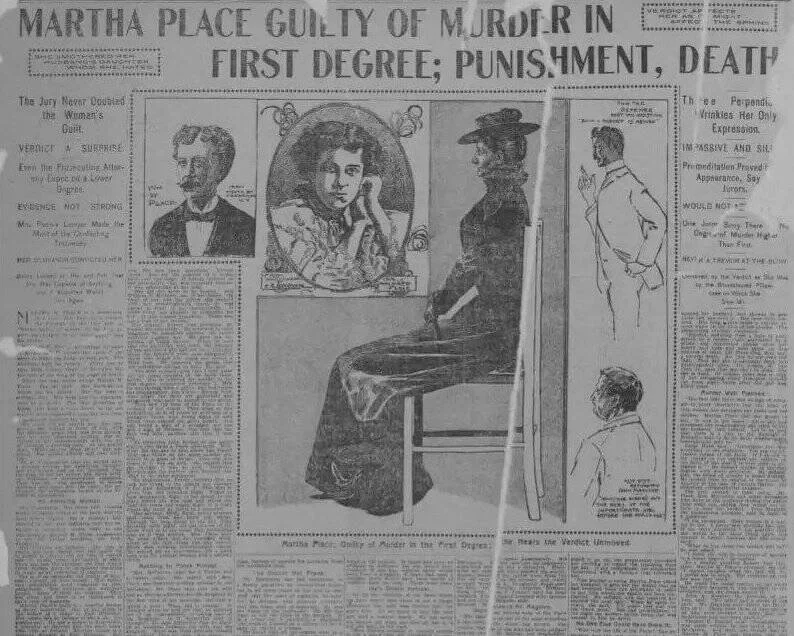

Martha’s trial began in July 1898 in Brooklyn. The courtroom was packed with reporters and curious onlookers. Journalists described her demeanor as stoic, often noting that her face rarely betrayed emotion. Some accounts described her as cold, while others saw moments of tension when her husband testified against her.

The prosecution presented evidence that Martha had acted deliberately. Testimony from William, medical findings, and Martha’s own words convinced the jury of her responsibility for Ida’s death. Despite her legal team’s efforts to argue diminished mental capacity due to her head injury and troubled life, the jury found her guilty of first-degree murder.

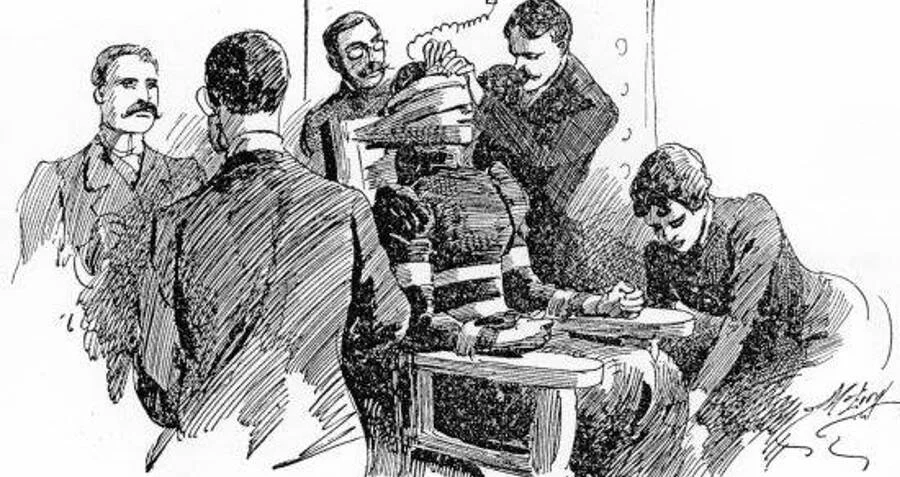

The verdict shocked many because of the penalty it carried: execution by electric chair. At the time, capital punishment was not uncommon, but the electric chair was a relatively new method, having been first used in 1890. Until then, no woman had faced execution by this device.

Appeals and Roosevelt’s Decision

Martha’s attorneys appealed the case and petitioned New York Governor Theodore Roosevelt for clemency. Public opinion was divided. Some argued that executing a woman was unthinkable, while others insisted that her crime deserved the full weight of the law. Governor Roosevelt, however, refused to intervene. He declared, “My sympathies in criminal cases are for the wronged and not the wrongdoer,” making clear his stance on justice and punishment.

Preparing for a Historic Execution

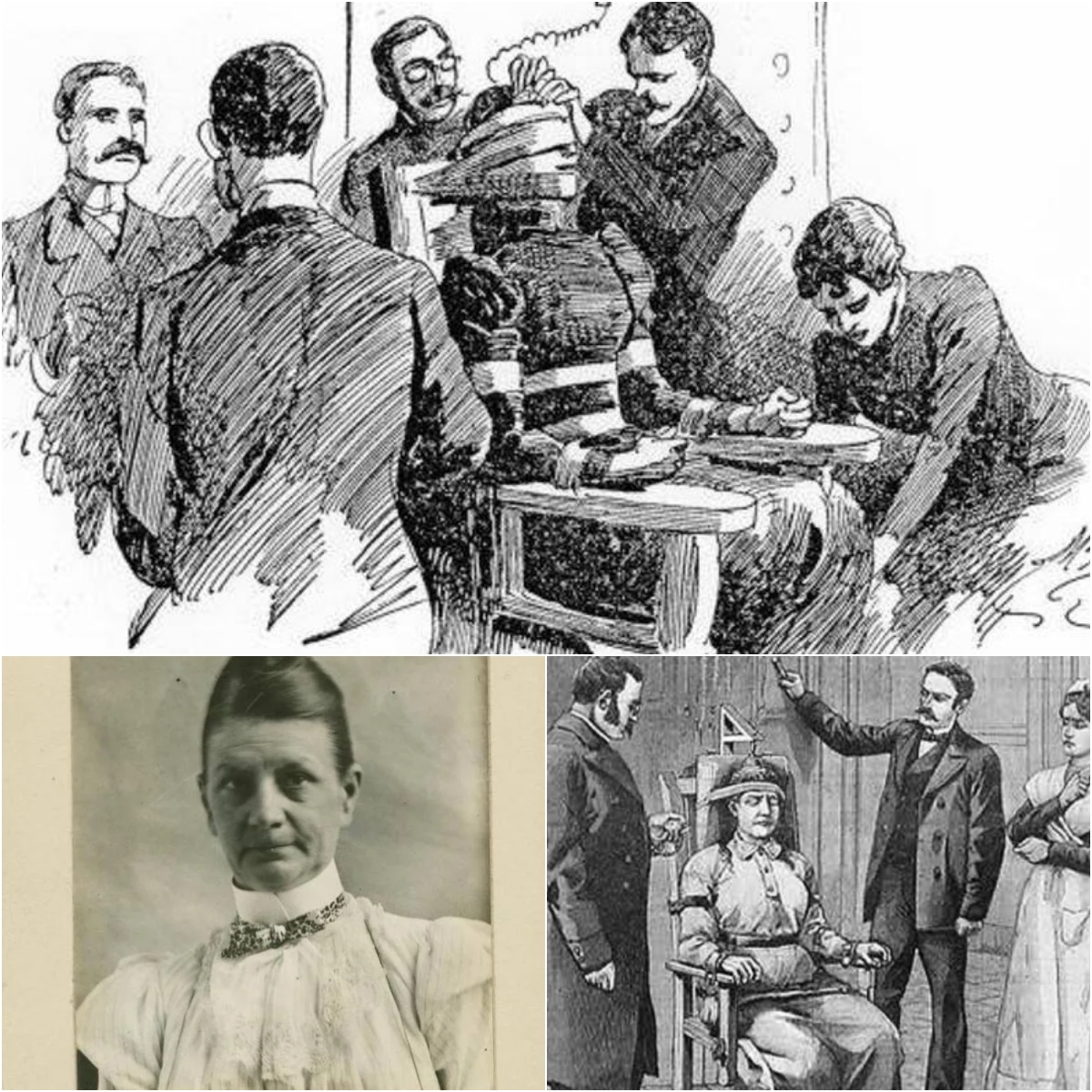

On March 20, 1899, Sing Sing Prison prepared for an unprecedented event. Adjustments had to be made because the electric chair had never been used on a woman before. Officials trimmed her hair to make room for electrodes and modified her clothing to allow for proper placement of the apparatus while maintaining modesty.

Accounts describe Martha as calm in her final hours. She wore a black gown of her own making and hoped, until the end, for a reprieve that never came. Witnesses noted her composure, with her final words reported to be a quiet appeal for divine mercy. Within moments, the execution was complete.

Media Sensation and Ethical Debate

The press documented every detail of Martha Place’s execution, turning it into a national story. Newspapers described her as both an unrepentant criminal and a tragic figure shaped by personal hardship. Public fascination centered not only on her crime but on the novelty of the method used.

The case intensified debates about the electric chair. Promoted in its early years as a more “modern” and supposedly humane alternative to hanging, the electric chair remained controversial. Technical issues in early executions had raised doubts about its reliability, and critics argued that it represented a brutal experiment in punishment. Martha’s case, being the first female execution of its kind, brought new attention to these concerns.

The Broader Legacy

Between 1890 and 2010, more than 4,000 people were executed by electric chair in the United States. Martha Place’s case remains unique because it was the first time this method was applied to a woman. Historians see her story as a turning point—not only in the history of capital punishment but also in the conversation about gender and justice.

Her life and actions underscore the destructive potential of jealousy, hardship, and unresolved trauma. At the same time, her execution highlighted how society at the time viewed equality in punishment: if men could face the electric chair, women would too. The logistical adjustments made by prison staff reflected the novelty of the situation, but ultimately, her sentence was carried out just as it would have been for any man.

Remembering Martha Place Today

More than a century later, Martha Place remains a subject of fascination. Her mugshot from Sing Sing and period newspaper clippings are shared in historical archives and online forums dedicated to true crime and legal history. For many, her case is a symbol of the harsh realities of late 19th-century justice and the media’s power in shaping public perception.

Her story also continues to influence academic discussions about capital punishment. Was the use of the electric chair truly more humane, as reformers of the time claimed? Did gender bias play a role in the way her case was covered and remembered? These questions keep her legacy relevant in debates over ethics, technology, and justice.

Conclusion

The story of Martha Garretson Place is one of tragedy, crime, and legal precedent. From her difficult early life to her troubled role as a stepmother, from the sensationalized trial to her historic execution, her case reflects the complexities of human emotion and the unforgiving machinery of the justice system.

Her execution as the first woman to die in the electric chair was not merely a punishment for her crime; it was a landmark moment in American history. It forced society to confront questions about equality, justice, and the evolving nature of capital punishment. More than a century later, Martha Place’s name endures as a reminder of how personal despair can intersect with public justice, leaving a story that is as haunting as it is historically significant.

Sources

-

The New York Times – Archival coverage of the Martha Place trial and execution

-

Smithsonian Magazine – History of women and capital punishment

-

Death Penalty Information Center – Historical execution statistics